Lamisil Tablets, pack, 14 pcs, 250 mg, for oral administration, for adults

Side effect

From the hematopoietic system: very rarely - neutropenia, agranulocytosis, pancytopenia. In very rare cases, when using the drug, the development of qualitative or quantitative changes in blood cells (neutropenia, agranulocytosis, thrombocytopenia, pancytopenia) was observed. If qualitative or quantitative changes in blood cells develop, the cause of the disturbances should be established and consideration should be given to reducing the dose of the drug or, if necessary, stopping therapy with Lamisil. From the immune system: very rarely - anaphylactoid reactions (including angioedema), cutaneous and systemic lupus erythematosus. From the nervous system: often - headache; sometimes - disturbances in taste, including their loss (usually recovery occurs within a few weeks after stopping treatment); very rarely - dizziness, paresthesia, hypoesthesia. There are isolated reports of cases of long-term disturbances in taste. In some cases, while taking the drug, there was a decrease in food consumption, which led to a significant decrease in weight. From the hepatobiliary system: rarely - hepatobiliary dysfunction (mainly cholestatic in nature), including very rare cases of severe liver failure (some fatal or requiring liver transplantation). In most cases where liver failure developed, patients had serious concomitant systemic diseases and the causal relationship of liver failure with Lamisil was questionable. From the digestive system: very often - a feeling of fullness in the stomach, loss of appetite, dyspepsia, nausea, mild abdominal pain, diarrhea. From the skin and subcutaneous tissue: very often - mild skin reactions (rash, urticaria); very rarely - serious skin reactions (including Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis); psoriasis-like skin rashes or exacerbations of psoriasis. Very rarely, cases of hair loss have been reported, although the cause-and-effect relationship of this phenomenon with taking the drug has not been established. If a progressive skin rash develops, treatment should be discontinued. From the musculoskeletal system: very often - arthralgia, myalgia. Other: very rarely - feeling of fatigue.

Lamisil tab 250mg N14 (Novartis)

LAMISIL is a broad-spectrum antifungal, fungistatic, fungicidal. Pharmacodynamics Terbinafine is an allylamine that has a broad spectrum of action against fungi that cause diseases of the skin, hair and nails, incl. dermatophytes such as Trichophyton (for example T. rubrum, T. mentagrophytes, T. verrucosum, T. tonsurans, T. violaceum), Microsporum (for example M. canis), Epidermophyton floccosum, as well as yeast fungi of the genus Candida (for example C. albicans) and Pityrosporum. In low concentrations, terbinafine has a fungicidal effect against dermatophytes, molds and some dimorphic fungi. Activity against yeast fungi, depending on their type, can be fungicidal or fungistatic. Terbinafine specifically inhibits the early stage of sterol biosynthesis in the fungal cell. This leads to ergosterol deficiency and intracellular accumulation of squalene, which causes the death of the fungal cell. Terbinafine works by inhibiting the enzyme squalene epoxidase in the cell membrane of the fungus. This enzyme does not belong to the cytochrome P450 system. When Lamisil® is administered orally, concentrations of the drug are created in the skin, hair and nails that provide a fungicidal effect. Pharmacokinetics After oral administration, terbinafine is well absorbed (>70%); The absolute bioavailability of terbinafine due to the first pass effect is approximately 50%. After a single oral dose of terbinafine at a dose of 250 mg, its Cmax in plasma is reached after 1.5 hours and is 1.3 mcg/ml. With continuous use of terbinafine, its Cmax increased by an average of 25% compared with a single dose; AUC increased 2.3 times. Based on the increase in AUC, it is possible to calculate the effective T1/2 - 30 hours. Food intake has a slight effect on the bioavailability of the drug (AUC increases by less than 20%), therefore no dose adjustment of Lamisil® is required when taken simultaneously with food. Terbinafine significantly binds to plasma proteins (99%). It quickly penetrates the dermal layer of the skin and concentrates in the lipophilic stratum corneum. Terbinafine also penetrates the secretions of the sebaceous glands, which leads to the creation of high concentrations in the hair follicles, hair and skin rich in sebaceous glands. It has also been shown that terbinafine penetrates into the nail plates in the first few weeks after the start of therapy. Terbinafine is metabolized quickly and to a significant extent with the participation of at least 7 isoenzymes of cytochrome P450, with the main role being played by the isoenzymes CYP2C9, CYP1A2, CYP3A4, CYP2C8 and CYP2C19. As a result of the biotransformation of terbinafine, metabolites are formed that do not have antifungal activity and are excreted primarily in the urine. No changes were detected in the equilibrium concentration of terbinafine in plasma depending on age. In pharmacokinetic studies of a single dose of Lamisil® in patients with concomitant renal dysfunction (Cl creatinine

Lamisil in the treatment of onychomycosis

ABOUT

Nichomycosis is one of the most common human diseases. It is currently believed that nail diseases caused by fungi occur in 50% of patients with lesions of the nail plates. In Russia, the number of patients with onychomycosis varies from 4.5 to 15 million people.

The causative agents of onychomycosis are dermatophytes, yeasts, and molds; however, their relationship in the spectrum of morbidity is assessed by researchers differently. In the vast majority (91.3%) of patients, dermatophytes are identified – primarily Tr. rubrum

(72%), less often –

Tr.

menthagrophytes (19.3%) [1, 15, 21] (Fig. 1).

In particular, Tr.

rubrum , as a rule, is the cause of damage to the nail plates of the feet;

yeasts usually affect fingernails, and non-dermatophytic molds, which cause 3–5% of onychomycosis, affect the feet [23]. Mostly yeasts and molds are found in combination with Tr.

rubrum .

Rice. 1. Proportions of pathogens in the etiology of onychomycosis

Predisposing factors for the development of mycotic infection include vascular diseases of the lower extremities (obliterating endarteritis, thrombophlebitis, varicose veins, Raynaud's syndrome), systematic microtrauma of the nail plate, as well as degenerative conditions. Typically, these factors complicate the treatment of onychomycosis, especially if the patient has a combined pathology of the nail (for example, mycosis against the background of psoriasis).

In the pathogenesis of onychomycosis, a significant role belongs to the pathology of carbohydrate metabolism, endocrine and neurological changes, and disorders of the immune system. The disease often develops against the background of long-term use of medications that suppress the body's defenses (glucocorticoids, cytostatics, broad-spectrum antibiotics). According to the literature [8, 23], onychomycosis is registered in 40% of cases in people over 65 years of age who have age-related immunosuppression.

The vast majority of cases of onychomycosis are characterized by a chronic persistent course. It is believed that when Tr. rubrum

this is due to the inability to develop a specific immune response against the fungus due to the activity of special T-suppressor cells. Suppression of the cellular and lack of inflammatory response to the pathogen may also be due to its predominant localization in the stratum corneum of the epidermis and nail plates.

The literature provides numerous data on the comparative effectiveness of various methods of treating onychomycosis: local use of antimycotics in the form of ointments, patches, varnishes, surgical removal of the nail plate followed by treatment of the nail bed with antifungal drugs, as well as systemic antimycotics [1, 2, 12, 28]. An analysis of publications on the problem indicates that in world medical practice there is still no ideal remedy and method for treating onychomycosis that would be suitable for all patients without exception, would not give any side effects and would provide a 100% clinical and etiological cure of the patient in a short time. Therefore, today the search and comprehensive study of new effective antimycotics that meet these requirements is justified.

A representative of the class of allylamines, chemical compounds included in the arsenal of the most effective treatments for dermatomycosis, is terbinafine (Lamisil, created in 1982 by the Swiss company Novartis).

To date, after multilateral clinical trials, Lamisil has become firmly established in the practice of treating patients with mycoses [11, 22, 29, 31]

This is a drug with a wide spectrum of antifungal activity [16, 34]. At therapeutic concentrations, it has a direct fungicidal effect on dermatophytes, yeasts and molds, both orally and when applied topically. The site of application of the drug is the cytoplasmic membrane of the fungal cell. The advantage of terbinafine is its action in the early stages of sterol metabolism, at the level of the squalene epoxidase cycle. By inhibiting the enzyme squalene epoxidase, terbinafine inhibits the formation of ergosterol, the main component of the cell wall of fungi, preventing their further reproduction [15, 19, 22].

The drug has a dual mechanism of action: fungicidal and fungistatic, with the fungicidal effect being the main one. It is caused by the accumulation of squalene in the fungal cell, which, like a kind of lipid sponge, extracts lipid components from membranes. Lipid granules accumulating inside the cell, gradually increasing in volume, rupture the defective cytoplasmic membranes, leading the fungal cell to death [11, 17]. The fungistatic effect is due to damage to the membranes of the fungal cell due to the suppression of ergosterol synthesis, which leads to the loss of the fungal cell’s ability to develop - it only survives.

The predominant fungicidal effect of Lamisil, which distinguishes it from previously created systemic antimycotics, determines the higher effectiveness of the drug, as well as a lower number of relapses when used, due to which treatment is cheaper than other systemic antimycotics [9, 14].

The drug is well absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract: 2 hours after a single dose of 250 mg, its plasma concentration is 0.8–1.5 mg/ml. Due to its lipophilicity, it accumulates in the dermis, epidermis, and adipose tissue, from where it is slowly absorbed into the blood [19]. Terbinafine also penetrates the secretions of the sebaceous glands, which leads to the creation of the highest possible concentrations in the hair follicles, hair and skin rich in sebaceous glands. The drug is detected in the stratum corneum of the epidermis within a few hours after oral administration, which is achieved by its excretion by the sebaceous glands and, to a lesser extent, by passive diffusion [11, 17]. Terbinafine is characterized by long-term persistence in the blood due to a continuous dosage regimen, which is an important component of its pronounced effectiveness. In the distal parts of the nails, its concentration remains for 48 weeks after the end of the course of therapy, which causes a positive fungicidal effect and makes it possible to cure onychomycosis without removing the nail plates [19, 29]. Biotransformation leads to the formation of metabolites that do not have antimycotic activity, which are excreted from the body mainly in the urine [9].

The distribution features of terbinafine include its lymphatic transport due to its lipophilicity and association with chylomicrons. Through the lymphatic vessels, terbinafine directly reaches infiltrative-suppurative and abscessed lesions complicated by lymphangitis. This nature of terbinafine transport, combined with its antibacterial properties, comparable to those of gentamicin, leads to a fairly rapid resolution of complicated forms of dermatophytosis [23].

The drug does not suppress liver enzymes, has little binding to cytochrome p-450, and as a result has virtually no effect on the metabolism of medications, i.e., the risk of drug interactions is minimal. This is an important advantage of the drug, since it ensures safety in the treatment of patients receiving concomitant therapy for intercurrent diseases (diabetes mellitus, diseases of the cardiovascular, nervous systems, etc.) [21, 31]. The bioavailability of terbinafine does not change as a result of co-administration with other drugs and food. At a concentration 5 times higher than the therapeutic one, terbinafine does not inhibit chemotaxis, phagocytosis and metabolic activity of leukocytes, i.e. does not have an immunosuppressive effect [34]. Moreover, the work of Barbareschi, 1993 [13] showed that in vitro incubation of polymorphonuclear neutrophils with terbinafine leads to an increase in their activity [13].

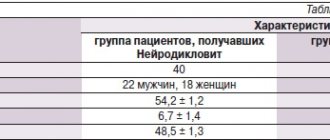

Lamisil has an excellent safety profile [20, 36, 39, 40]. Its safety is comparable to placebo [29]. According to data presented by a number of authors [16,27], based on the analysis of case histories of 25,884 patients taking tablets, side effects that occurred when taking Lamisil are extremely rare and relate mainly to mild phenomena from the gastrointestinal tract (Table 1 ).

All noted properties of the drug contributed to its rapid introduction into clinical practice in more than 80 countries around the world [17, 21, 25, 27]. The data from foreign researchers presented in the table indicate the high effectiveness of Lamisil in the treatment of onychomycosis. Many domestic scientists have also noted the positive experience of treatment with Lamisil, demonstrating very impressive results.

So, according to A.A. Kubanova [4], positive clinical effects and microbiological cure were noted in 94.4% of patients. The results of Yu.V. are indicative. Sergeev [9], which demonstrates clinical and mycological cure in 82% of patients. Data from N.S. Potekaeva [8] indicate the high effectiveness of Lamisil: mycological cure was obtained in 96% of patients (see Table 2). V.M. Leshchenko and G.M. Leshchenko [6] assess the results of treatment of patients with onychomycosis of the feet and hands, combined with lesions of smooth skin, as positive. At the end of the traditional course of treatment (250 mg once for 12 weeks), clinical recovery was observed in 96% of patients. The drug was well tolerated. In 478 patients after treatment with Lamisil, no fungi were microscopically detected in the material from the nail plates, and 6 months after the start of treatment, clinical and microbiological cure was stated in all of them.

According to V.A. Molochkov [5], in the treatment of patients with onychomycosis, the use of Lamisil turned out to be highly effective, positive clinical effects and microbiological cure were noted in 95.2% of patients. Interesting data on the use of Lamisil in patients with diabetes mellitus were obtained by S.A. Burova [3]. The presented long-term results (6 months after the end of treatment with Lamisil) indicate that clinical recovery is observed in 85.7% of patients, microbiological sanitation in 89.3%. HE. Pozdnyakova demonstrates the effectiveness and safety of Lamisil in 48 patients with chronic liver diseases without exacerbation [8] in the compensated and subcompensated stages: after completion of therapy, mycological cure was observed in 100% of patients. The information on the use of Lamisil in immunodeficiency states is encouraging, given that the number of these patients is increasing every year. To date, 82 cases of the use of Lamisil tablets for immunodeficiencies have been described: AIDS [26, 37, 38], Down syndrome, after organ transplantation [18, 24, 27].

Yu.K. Skripkin and Zh.V. Stepanova [10], summarizing the experience of domestic and foreign researchers, once again emphasized the effectiveness and safety of Lamisil, good tolerability, and convenient application regimen. The effectiveness of treatment, according to their data, was 94%.

We observed 32 patients with onychomycosis of the feet (18 men, 14 women) aged from 25 to 55 years with a disease duration of 1 to 15 years. Concomitant diseases were identified in 28% of patients, including gastritis, colitis, thyroid dysfunction; 50% of patients considered themselves practically healthy. Predisposing factors determining the development of the mycotic process were identified in 100% of patients. Thus, 26 patients were regular visitors to swimming pools, 18 to saunas; 14 patients were involved in professional sports, which is associated with permanent trauma to the nail plates. The diagnosis of onychomycosis was established in each case on the basis of the clinical picture of the disease and the detection of fungi during microscopic examination of the affected nail plates. In 20 patients, in addition to onychomycosis (damage from 1 to 16 nail plates), there was damage to the skin of the corresponding localization: feet and hands (4 patients), smooth skin of the torso (6 patients), large folds (10 patients). According to the clinical picture, the nail plates were affected mainly by a mixed type, i.e. in the same patient on different fingers they were changed in a hypertrophic, normotrophic type with symptoms of onycholysis and the area of nail damage from marginal (5–10%) to total, involving the skin of the feet and palms in the process with skin changes characteristic of rubrophytosis exaggeration of skin furrows, fine-plate (floury) peeling, hyperkeratosis, maceration of the epidermis, cracks in the interdigital folds of the skin of the feet.

Patients received Lamisil orally at a dose of 250 mg per day for 12 weeks, and during therapy, a general blood test, urine test, and liver function tests were examined. In each case, shoes were treated at home with a 25% formaldehyde solution or a 0.5% chlorhexidine digluconate solution twice with an interval of 1 month. In order to increase the intensity of growth of the nail plate, 5 patients were prescribed phytin and zinc-containing vitamin complexes orally.

The patients tolerated the treatment well. Among the side effects, 1 patient experienced a temporary loss of taste: this phenomenon resolved on its own without requiring discontinuation of the drug.

Control microscopic examination was carried out 3, 4, 6 months after the start of treatment, and 6 months after the end of therapy, in 100% of cases the results of microscopic examination were negative. In 4 patients, despite the absence of fungi on microscopic examination, the nail plates remained dystrophically changed, and in each case they had a history of trauma to the corresponding nail.

As a result of treatment, skin rashes, especially in large folds, resolved within 2–3 weeks. Affected nails with an affected area of up to 60% on the feet were replaced with visually healthy ones after 5–6 months, i.e. 3–4 months after stopping taking Lamisil. No relapses of the disease were detected (9–14 months of follow-up).

Thus, based on literature data and the results of our own research, it can be argued that the advent of Lamisil has led to a significant improvement in the prognosis of patients suffering from onychomycosis, which was previously difficult to treat and characterized by a persistent course. Lamisil therapy has changed the view that onychomycosis is difficult to cure: the drug is highly effective, providing a high cure rate in a shorter period of time than previous generations of antimycotics. The fungicidal effect, active penetration of Lamisil into keratin and its long-term preservation in the nail plate, combined with the relative rarity of serious undesirable effects and relapses, have made the drug the drug of choice in the treatment of fungal infections of nails and smooth skin. It should be noted that it is currently included in the list of drugs for preferential treatment of disabled people and pensioners at the expense of insurance companies.

The list of references can be found on the website https://www.rmj.ru

Terbinafine–

Lamisil (trade name)

(Novartis Pharma)

References:

1. Afanasyev D.B. “Complex outpatient treatment of onychomycosis using biologically active dressings”, abstract of the dissertation of Candidate of Medical Sciences. Sciences, M., 1996, 23.

2. Bormotov V.Yu. “Outpatient treatment of patients with onychomycosis caused by red trichophyton”, Abstract of the dissertation of candidate of medical sciences., M., 1983; 19.

3. Burova S.A., Talalaeva S.M., “Long-term results of treatment of onychomycosis in patients with diabetes mellitus” “Russian Journal of Skin and Venereal Diseases” 2000, No. 5, pp. 31–33.

4. Kubanova A.A., Sukolin G.I., Yusuf M., Yazdy M.Sh. “Bulletin of Dermatology and Venereology” 1995, No. 6, pp. 42–43 “The use of Lamisil in mycological practice.”

5. Kurcheva O.P., Molochkov V.A. “Lamisil is an effective treatment for onychomycosis” “Russian Journal of Skin and Venereal Diseases” 1998, No. 1, 47–49.

6. Leshchenko V.M., Leshchenko G.M. “Treatment of onchomycosis with Lamisil” “Bulletin of Dermatology and Venereology” 1998, No. 2, pp. 61–64.

7. Lykova S. G., Pozdnyakova O. P. “Bulletin of Dermatology and Venereology”, 2000, No. 4

8. Potekaev N. S. “Bulletin of Dermatology and Venereology”, 1999, No. 5

9. Sergeev Yu.V., Potekaev N.S., Leshchenko V.M., Larionova V.N. “Bulletin of Dermatology and Venereology” 1995 No. 5 pp. 54–56 “Lamisil: improving the treatment of onychomycosis caused by dermatophytes.”

10. Skripkin Yu.K., Stepanova Zh.V. “Bulletin of Dermatology and Venereology” No. 6, 1999. 11 11. Alpsoy E., Yilmanz E., Basaran E. Intermettent therapy with terbinafine for dermatophyte toe onychomycosis a new approach.– J. Dermatol, 1996, 23:259–262

12. Back DJ, Tjia JF, Abel SM Azoles, allylamines and drug metabolism. Br. J. Dermatol. 1992; 126(Suppl. 33): 14–18.

13. Barbareschi M, Vago, Colombo D., Bevilacqua M. mycoses 36: 405–9 (1993), (LAS 360)

14. Clayton JM In vitro activity of terbinafine, Clin Ep.Dermatol. 1989; 14: 101–103.

15.Clayton JM, Hay KJ, Bnt. J. Dermatol. 1994 vol.130 suppl.43, p.9–11.

16. De Cnyper “Long-term outcome of onychomycosis treatments” Cl. Dermal, 1998; TZ

17. Einarson TR, Lupta AK, Shear NH, Arikian S. Clinical and economic factors in the treatment of onychomy costs. Pharmacoeconomics 1996: 307–320.

18. EnsenP. et al. ActaDermato-Venereologica76: 280–1 (1996)

19.Faergemann J., Lehender H., Milleriouv L. Levels of terbinafine in plasma, stratum comeum, dermis–epidermis (without stratum comeum), sebum, hair and nails during and after 250 mg terbinafme orally once daily for 7 and 14 days .– Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 19:121–6.

20. Hall M., Monka C., Krupp P., O'Sullivan Safety of oral terbinafme. Results of a Postmarketing Surveillance study in 25884 patients.–Archives of Dermal, 1997, v. 1213–1218.

21. Goodfield MJD, Br. J. Dermatol. 1992; 126 suppl. 33–35

22. Jones T.S. Overview of the use of terbinafme (Lamisil) in children. Br. J. of Dermatology; 1995; 132:683–689.

23. Lamisil (terbinafine hydrochloride tablets). Physicians' Desk Reference. 51 st col Montvale, NJ: Medical Economics; 1997.2334–95.

24. La Placa M et al. J. Dermatol. Tream 6:51–2(1995) (LAS 446)

25. Matsumoto T., Januma H., Kaneko S., Jakasu H., Nishiyama S. Clinical and pharmacokinetic investigations of oral terbinafme in patients with tinea unguium. – Mycoses 1995; 38: 135–144.

26. Nandwani R. et al. Br J Dermatol. 134 (suppl. 46): 22–24 (1996) (LAS 563)

27. Norden J et al. Scand J Infect Lis 23: 377–82 (1991) (LAS 188) 2 8. Onychomy costs and terbinafine. Lancet 1990; 335:636

29. Polak A., Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology; Chemotherapy of Fungal Diseases 1990, p.96–153.

30. Roberts DT et al J. Amer. Assoc. Dermatol. 1994; 31 (suppl.2) 578–581.

31. Roberts DT Prevalence of dermatophyte onychomycosis in the United Kingdom: results of an omnibus survey.– Br. J. Dermatol. 1992; 126 (Suppl. 39): 23–7

32. Roberts Dabriol. Abstracts of the 19th world congress of dermatology, 1997, Sydney, Australia

33. Rynder NS The mechanism of action of terbinafine. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 1989; 14:98–100.

34.Shauder M. Mycoses 31:259–67 (1988) (LAS 62)

35.Singer MJ et al, J.Amer.Acad Dermatol. 1997, 37; 765–771.

36.Suhonen R. and Neuvonen P., Rev.Contemp.Pharmacother, 1997; 8; 373–386.

37. Villars V et al. Br J Dermatol 126(suppl 39):61–9 (1992) (LAS 208)

38. Velthuis PJ et al. Br J Dermatol 144–6(1995) (LAS 465).

39. Williams and Hall M. “A review of the Safety of oral terbinafine (Lamisil) when used with oral coutraceptives and in pregnancy in a Postmarketing Surveillance Study.”– Book of abstracts, poster No. 81, Sing., 1988, 12– 20.06, pm 18.

40. Williams T., Lanslandt J. and Jones T. A review of the efficacy and tolerability of terbinafine in children. Poster presented at the 8th International Congress Pediatric Dermatology, 1998.