The term “acute coronary syndrome” has been used since the time when doctors began to choose active methods of therapy before confirming the diagnosis of large-focal myocardial infarction.

- Classification

- Pathogenesis

- Symptoms and diagnosis

- Treatment of acute coronary syndrome

- Management of patients after discharge from hospital

The term ACS refers to a combination of a certain number of symptoms that indicate unstable angina or myocardial infarction. Acute coronary syndrome can mean several patient conditions:

- myocardial infarction without segment elevation 5G;

- myocardial infarction with segment elevation 5G;

- unstable angina;

- myocardial infarction, diagnosed by changes in the activity of cardiac-specific enzymes, biomarkers, and late ECG signs.

Within 24 hours after a person is admitted to the hospital, this diagnosis must be changed to one of the following:

- “myocardial infarction with O wave”;

- “myocardial infarction without O wave”;

- “unstable angina”;

- “stable exertional angina” or “other disease”.

Classification

Based on manifestations and electrocardiogram data, two types of acute coronary syndrome are distinguished:

• acute coronary syndrome without 5T segment elevation (which is a consequence of myocardial infarction (MI) without 5T segment elevation or unstable angina);

• acute coronary syndrome with segment elevation 5G.

There is more than one classification of unstable angina; the 2000 classification, authored by Hamm-Braunwald, is often used. The worst prognosis is for unstable angina that developed within two days.

From a clinical point of view, the most unfavorable prognosis is unstable angina that develops within 48 hours.

| A - develops in the presence of extracardiac factors that increase myocardial ischemia (secondary unstable angina) | B - develops without extracardiac factors (primary unstable angina) | C - develops within 2 weeks after myocardial infarction (post-infarction unstable angina) | |

| I - first appearance of severe angina, progressive angina, without angina at rest | 1A | № | 1C |

| II - angina at rest in the previous month, but not in the next 48 hours (angina at rest, subacute) | ON | IV | NS |

| III - angina at rest in the previous 48 hours (angina at rest, acute) | SHA | SHV ShV troponin (-) ShV troponin (+) | Shs |

Pathogenesis

The following factors are important in the pathogenesis of acute coronary syndrome.

- Thrombosis of the coronary artery of varying severity

- Tear or erosion of atherosclerotic plaque

- Distal coronary artery embolization

- Spasm of the coronary artery

- Inflammation

Tearing or erosion of an atherosclerotic plaque occurs when its instability appears. And instability, in turn, can arise due to the following reasons:

- thin fibrous capsule with a thin layer of superficially damaged collagen;

- large size of the lipid core;

- high concentration of macrophages and, accordingly, tissue factors (metalloproteinases);

- low density of smooth muscle cells.

Symptoms and diagnosis

Manifestations (clinic) of acute coronary syndrome without 5T segment elevation are divided into two nosological forms, which in most cases differ only in the severity of symptoms:

- myocardial infarction without segment elevation 5G;

- unstable angina.

Non-elevation myocardial infarction 5T is an acute myocardial ischemia that is so severe and prolonged that it can cause myocardial necrosis.

- At the initial stage, the rise of the 5T segment on the ECG is not recorded. In most patients, pathological 0 waves also no longer appear. In such patients, myocardial infarction without 0 waves is diagnosed.

- Myocardial infarction without segment elevation 5T differs from unstable angina only by the detection of markers of myocardial necrosis in the blood.

Unstable angina is acute myocardial ischemia that cannot cause myocardial necrosis. The elevation of the 5T segment is also not visible on the electrocardiogram. Markers of myocardial necrosis are not released into the bloodstream due to the absence of necrosis.

Complaints

For the diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome, a previous history of coronary artery disease is important. In typical cases of acute coronary syndrome, a person experiences pain that lasts longer than 15 minutes. For timely diagnosis, patient complaints about the occurrence of nocturnal angina attacks, as well as the development of angina attacks at rest, are important.

Atypical signs . They mainly occur in people over 75 years of age, young people under 40 years of age, patients diagnosed with diabetes mellitus, and also in women. The clinic could be like this:

- Pain in the epigastric region

- Pain at rest

- Chest pain with signs typical of pleurisy

- Stitching pain in the chest

- Increased shortness of breath, deterioration of exercise tolerance

Electrocardiography

ECG is a very significant method for diagnosing acute coronary syndrome: displacement of the 5T segment and changes in the G wave are characteristic. It is preferable to record an electrocardiogram at the stage of manifestation of pain. A necessary condition for diagnosing acute coronary syndrome is a comparison of several ECG recordings over time. If, in the presence of a typical pain syndrome, there are no changes on the ECG, then non-cardiac causes of pain are excluded.

Laboratory research

Shown:

- conducting a general blood test;

- determination of biochemical parameters.

To distinguish myocardial infarction without 5T elevation from unstable angina in the context of acute coronary syndrome, it is necessary to determine the concentration of cardiac troponins (qualitatively or quantitatively). Doctors also measure the amount of glucose in the blood plasma to assess carbohydrate metabolism. If it is violated, the course of ACS may worsen.

The training and practical activities of a general practitioner and a doctor providing specialized medical care to cardiac patients at the outpatient or inpatient stage of treatment are different. People who visit a GP often have a different clinical picture, since the early manifestations of any disease are less specific.

.

Relevance of the problem

More than 10 years ago, J. Allen, UK Department of Health adviser for primary care, said: “The general practice student needs to be where the patients are.” For a doctor of any specialty, the process of continuous learning is an integral part of the profession.

Discussing the diagnostic issues of acute coronary syndrome (ACS), we will focus on typical clinical situations, not forgetting that every year there is an increase in asymptomatic and atypical forms of myocardial infarction throughout the world.

One of the main reasons for the emergence of this trend is considered to be an increase in the number of patients with comorbid pathology, the presence of which changes the clinical symptoms during the development of ACS. Providing medical care for a large number of concomitant diseases requires the GP to have the skill of identifying a priority problem. It is formed as practical experience grows, subject to good theoretical knowledge in the field of cardiology and therapy.

Correct assessment of early nonspecific manifestations of the disease is very important for the primary care physician. In the vast majority of cases, developing ACS is the most dangerous condition among comorbid pathologies and requires quick professional action, as well as communication skills with a patient in critical condition.

Focusing on socioeconomic characteristics in the provision of primary health care to the population includes the ability to reconcile the health care needs of individual patients with the needs of the entire population served and with the available resources of the health care system.

Despite improvements in medical technology, the differential diagnosis of chest pain remains challenging, as it can be caused by many diseases and conditions, as well as their combinations.

Of particular importance is the timely and accurate recognition of prognostically unfavorable clinical situations requiring special treatment tactics. ACS refers to a pathology, the relevance of the fastest possible diagnosis of which is well known and beyond doubt.

However, overdiagnosis in this case is also a significant problem. Abroad, up to 90% of people with acute chest pain referred to emergency departments do not have acute coronary pathology. According to Russian specialists, the diagnosis of ACS is not confirmed in a third of patients admitted to the hospital.

Unjustified invasive and drug treatment significantly increases the costs of the healthcare system, worsens the course of the disease leading to the development of pain, and also creates additional risks associated with hospitalization and diagnostic procedures, including infectious and procedural complications.

Diagnostic Basics

The term “acute coronary syndrome” is not a diagnosis and is used at the stage of initial medical contact with the patient until the underlying disease is verified. This is a clinical and electrocardiographic phenomenon that combines nosological forms that are common in pathogenesis (unstable angina, acute myocardial infarction with or without ST segment elevation) and suggests the presence of an unstable atherosclerotic plaque in the coronary artery, partially or completely occluding the lumen of the vessel.

A correct understanding of the pathogenesis of ACS justifies the need for GPs to make a quick decision about the possibility and methods of restoring blood flow in the infarct-related artery. A sufficient minimum of information in this situation is the clinical picture of the developing acute event and ECG data, which should be recorded within 10 minutes from the moment of initial medical contact with the patient. Depending on the recorded changes in the ECG, ACS is differentiated at the prehospital stage with or without ST segment elevation. Each option, while the clinical picture and pathogenesis of development are common, differs in individual tactics and strategy at the prehospital and inpatient stages of treatment.

Clinically, the classic version of ACS is manifested by the development of intense pain in the chest of a pressing, squeezing or burning nature with possible irradiation to the left or both arms, interscapular region, neck, lower jaw lasting more than 15–20 minutes.

Among the atypical forms of developing myocardial infarction, the following should be noted:

- painless (no status anginosus, ischemic ECG changes),

- asthmatic (the equivalent of pain is shortness of breath or an attack of acute left ventricular failure),

- abdominal (pain or discomfort is localized in the epigastric region),

- arrhythmic (paroxysms of ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation, atrioventricular blockade are considered pathognomonic rhythm disturbances in ACS),

- peripheral (the clinical manifestation of this option is loss of consciousness due to a significant decrease in stroke volume).

The development of ACS with persistent ST segment elevation in most cases suggests the presence of acute thrombotic occlusion of the coronary artery and requires the fastest possible reperfusion intervention. The preferred method of reperfusion in this situation is to perform primary percutaneous coronary intervention, which involves emergency transportation of the patient to the hospital with a predicted time from initial medical contact to inflation of the balloon in the infarct-related artery of less than 90 minutes. If it is not possible to meet the specified time range due to various circumstances, patients with ST-segment elevation ACS should undergo thrombolytic therapy as early as possible in the absence of contraindications to the administration of antithrombotic drugs.

Non-ST segment elevation ACS can manifest as ST segment depression, T wave inversion, and absence of electrocardiographic changes.

The reperfusion strategy is limited to primary percutaneous coronary intervention; thrombolytic therapy is not used in this type of ACS. To decide the need and urgency of coronary intervention at the prehospital stage, clinical factors such as hemodynamic instability, refractory pain, the development of life-threatening arrhythmias, cardiogenic shock, mechanical complications of myocardial infarction, transient ST-segment elevation on the resting ECG, or persistent depression should be assessed ST segment.

If a patient with pain in the chest has post-infarction cardiosclerosis, stable angina pectoris or an asymptomatic form of coronary artery disease (silent myocardial ischemia), the detection of a negative T wave or an electrocardiographic pattern of scar changes can cause difficulties in differential diagnosis with fresh myocardial necrosis. Especially if there are no previously recorded electrocardiograms.

Usually, a careful questioning and examination of the patient allows one to exclude acute myocardial infarction, but even here, difficulties are possible at first. Mainly with a “frozen” ECG form and the absence of reliable information about the characteristics of a previously suffered myocardial infarction. In all these cases, emergency hospitalization of patients with coronary heart disease is justified - most of them will spend no more than a day in the intensive care unit (unit).

Choice of therapy

When the first signs of ACS appear, the patient must stop physical activity, take nitroglycerin sublingually, and if anginal pain persists for 15–20 minutes or if pain in the chest resumes after taking nitroglycerin, immediately call an ambulance.

If the primary contact with a patient who develops ACS is made by a GP, his responsibilities include assessing clinical symptoms, recording an ECG, providing first aid, and calling an ambulance. The correct interpretation of ECG data in this case is of fundamental importance when choosing organizational and treatment tactics.

Drug therapy, starting at the prehospital stage, is aimed at relieving pain, preventing complications and creating optimal hemodynamic conditions for maximum myocardial recovery.

The following groups of drugs are used:

- anticoagulants,

- combined antiplatelet therapy,

- beta blockers,

- angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors,

- statins (in accordance with Appendix 2 of the resolution of the Ministry of Health dated 06.06.2017 No. 59).

conclusions

Thus, for a correct medical opinion that determines the choice of tactics for managing a patient with ACS, a thorough critical analysis of all existing symptoms, medical history and ECG data is required, as well as constant vigilance regarding rarer causes of chest pain.

When making a differential diagnosis of myocardial infarction with other cardiac and non-cardiac diseases, it is necessary to be guided by some general considerations:

1. Correspondence of the diagnosis of myocardial infarction to the gender and age of the patient, the presence of risk factors.

2. The occurrence of episodes of chest pain with a similar clinical picture in the past and their outcomes.

3. The presence of anamnestic indications of diseases, complications of which may be mistaken for myocardial infarction.

4. In all doubtful cases, with the exception of acute surgical pathology, overdiagnosis of myocardial infarction is the least evil.

Modern approaches to the treatment of patients with ACS, using the capabilities of interventional and, if necessary, cardiac surgical treatment methods, as well as effective drug technologies, can improve the prognosis and quality of life of patients after ACS.

On the other hand, we must not forget that coronary heart disease is a chronic progressive disease of the cardiovascular system that requires lifelong drug therapy, smoking cessation, lifestyle modification, daily physical activity for at least 30 minutes, normalization of body weight, control blood pressure, adequate daily consumption of vegetables and fruits, limiting the intake of salt and trans fats.

The GP's tasks include the need to outline to the patient the absolute importance of regular medication intake for the secondary prevention of circulatory system diseases and the prevention of cardiovascular complications.

Treatment of acute coronary syndrome

Hospitalization

A patient with acute coronary syndrome should be admitted to the intensive care unit or intensive care unit for a day. Whether to leave the patient there further is determined by doctors, focusing on ECG indicators over time, his condition (severity), blood tests, etc.

Medicines

The following groups of drugs are used to treat acute coronary syndrome:

- p-blockers

- Nitrates

- Thrombolytic therapy indicated for segment elevation

- Slow calcium channel blockers

- Antithrombotic antithrombin drugs: heparin sodium, low molecular weight heparins - nadroparin calcium, enoxaparin sodium, dalteparin sodium

- Antithrombotic antiplatelet drugs: acetylsalicylic acid, clopidogrel, abciximab, eptifibatide

Nitrates

Nitrates are prescribed to those who have persistent episodes of myocardial ischemia (the clinical picture is mainly pain). Administered intravenously. The dosage is increased until the symptoms disappear. But the clinical picture may persist, but side effects appear, then the nitrates are canceled. Side effects are manifested mainly by headaches or increased blood pressure. If the effect of the drugs is achieved, oral medications are then prescribed instead, according to the recommendations of the 2003 VNOK.

If nitrates are administered IV, the infusion rate should initially be 10 mcg/min. The dose is then increased by 10 mcg/min every 3-5 minutes until symptoms begin to subside or the blood pressure responds.

p-blockers

Drugs from this category have the following effects:

- They reduce myocardial oxygen consumption due to systolic blood pressure and afterload, a decrease in heart rate, and a weakening of myocardial contractility.

- They increase coronary blood flow by improving diastolic perfusion, increasing distal coronary perfusion, and favorable epicardial-endocardial shift.

An effective medicine is Propranolol, the initial dose of which is 0.5-1.0 mg. After an hour, the patient should take the medicine orally at a dose of 40-80 mg every 4 hours up to a total dose of 360-400 mg per day. Metoprolol is effective, its initial dose is 5 mg, administered intravenously over 1-2 minutes. A repeat dose is administered every 5 minutes until the total reaches 15 mg. 15 minutes after the last intravenous administration, oral administration of 50 mg every 6 hours for 48 hours is indicated. Further, the intervals between doses can be increased. The maintenance dose is 100 mg 2-3 times a day. The desired effect is provided by another drug from the series of p-blockers - Atenolol, which is first administered in a dose of 5 milligrams.

Heparin

Unfractionated heparin is used as an anticoagulant treatment. But taking it can lead to bleeding from various parts of the body and organs. To avoid this, you need to monitor the patient's blood coagulation system. The starting dose ranges from 60 to 80 units/kg, it cannot exceed 5000 units.

An alternative to unfractionated heparin is low molecular weight heparins . Their administration is simple, sensitivity to platelet factor 4 is less than that of unfractionated heparin, which is one of the advantages of this group of drugs. The following tools are relevant:

- Dalteparin sodium

- Enoxaparin sodium

- Nadroparin calcium

Acetylsalicylic acid

Therapy with these drugs more than halves the risk of death and the development of MI in people with ACS without elevation of the 5G segment. The first dose is 250-500 mg; only uncoated tablets are used. Next you need to take 75-325 mg orally once a day.

Clopidogrel

This drug is prescribed mainly to patients with a high risk of myocardial infarction and death. On the first day you need to apply a loading dose, which is 300 mg, then the dose is 75 mg per day. The course of treatment is 1-9 months.

Conducting a stress test

It is performed for those who are in the low-risk group on days 3-7 after a characteristic attack in the absence of repeated episodes of myocardial ischemia at rest.

Diagnosis and treatment of acute coronary syndrome: from understanding principles to implementing standards

Definition

As defined in the 2000 American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association guidelines, acute coronary syndrome includes any group of symptoms suggestive of acute myocardial infarction (MI) or unstable angina (UA). The main clinical variants of ACS include:

- MI with ST segment elevation;

- Non-ST segment elevation MI;

- MI diagnosed by enzyme changes or biomarkers;

- MI diagnosed by late ECG signs;

- NS.

It should be emphasized that the diagnosis of ACS is temporary, “working” and is used to identify a category of patients with a high probability of MI or NS at the first contact with them. Treatment of patients with ACS begins before obtaining information necessary and sufficient to confidently make a nosological diagnosis. After identifying any of the above clinical conditions, therapy is adjusted based on the results of diagnostic tests.

Pathogenesis

The leading pathogenetic mechanism of ACS is thrombosis of the coronary artery affected by atherosclerosis

. A thrombus forms at the site of rupture of an atherosclerotic plaque. The likelihood of plaque rupture depends on its location, size, consistency and composition of the lipid core, the strength of the fibrous capsule, as well as the severity of the local inflammatory reaction and tension of the vessel wall. The immediate causes of damage to the plaque shell are the mechanical effects of blood flow and the weakening of the fibrous capsule under the influence of proteolytic enzymes secreted by macrophages. The contents of the plaque are characterized by high thrombogenicity - its effect on the blood leads to a change in the functional properties of platelets and the launch of the coagulation cascade. A certain role in the development of ACS is played by spasm of the coronary artery at the location of the damaged plaque. In cases where obstruction of the patency of the coronary artery is caused by its spasm and/or the formation of a platelet aggregate (that is, it is reversible), the clinical picture of NS develops. The formation of a red thrombus that does not completely block the lumen of the vessel leads to the development of MI without a Q wave. With complete thrombotic occlusion of the coronary artery, an MI with a Q wave is formed.

Diagnostics

Recognition of ACS is based on three groups of criteria. The first group consists of signs determined during questioning and physical examination of the patient, the second group - data from instrumental studies, and the third - results of laboratory tests.

Typical clinical manifestations of ACS are anginal pain

at rest for more than 20 minutes, first-time angina of functional class III, progressive angina. Atypical manifestations of ACS include varied pain in the chest that occurs at rest, epigastric pain, acute digestive disorders, pain characteristic of pleural damage, and increasing shortness of breath. Physical examination of patients with ACS often does not reveal any abnormalities. Its results are important not so much for the diagnosis of ACS, but for detecting signs of possible complications of myocardial ischemia, identifying heart diseases of a non-ischemic nature and determining extracardiac causes of the patient’s complaints.

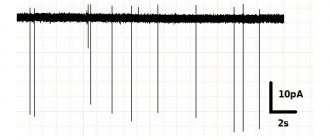

The main method of instrumental diagnosis of ACS is electrocardiography

. The ECG of a patient with suspected ACS should, if possible, be compared with data from previous studies. In the presence of appropriate symptoms, NS is characterized by ST segment depression of at least 1 mm in two or more adjacent leads, as well as T wave inversion with a depth of more than 1 mm in leads with a predominant R wave. Developing MI with a Q wave is characterized by persistent ST segment elevation , for Prinzmetal's angina and developing MI without a Q wave – transient ST segment elevation (Fig. 1). In addition to the usual resting ECG, Holter monitoring of the electrocardiosignal is used to diagnose ACS and monitor the effectiveness of treatment.

Rice. 1. Variants of ACS depending on ECG changes

Of the biochemical tests used to diagnose ACS,

the determination of the content of cardiac troponins T and I in the blood

, an increase in which is the most reliable criterion of myocardial necrosis.

A less specific, but more accessible criterion for determination in clinical practice is an increase in the blood level of creatine phosphokinase (CPK) due to its isoenzyme MB-CPK. An increase in the content of MB-CPK (preferably mass rather than activity) in the blood by more than twice as compared to the upper limit of normal values in the presence of characteristic complaints, ECG changes and the absence of other causes of hyperenzymemia allows one to confidently diagnose MI. An increase in the level of MB-CPK and cardiac troponins is recorded 4–6 hours after the onset of formation of a focus of myocardial necrosis. The earliest biomarker of MI is myoglobin

- its content in the blood increases 3-4 hours after the development of MI. To rule out or confirm the diagnosis of MI, repeat blood tests are recommended within 6 to 12 hours after any episode of severe chest pain. The listed tests become especially important in the differential diagnosis of MI without a Q wave and NS.

Traditional biomarkers of myocardial necrosis, such as aspartic aminotransferase, lactate dehydrogenase, and even total CPK, due to insufficient sensitivity and specificity, are not recommended for the diagnosis of ACS. In practical healthcare conditions, the funds spent on the purchase of reagents for their determination should be directed to the implementation of recommended diagnostic tests.

Risk assessment

During the first 8–12 hours after the onset of clinical symptoms of ACS, it is necessary to ensure the collection of diagnostic information in a volume sufficient for risk stratification. Determining the degree of immediate risk of death or development of MI is fundamentally important for choosing treatment tactics for a patient with ACS without persistent ST segment elevation.

Criteria for a high immediate risk of death and MI include:

repeated episodes of myocardial ischemia (repeated anginal attacks in combination or without combination with transient depression or ST segment elevation);

increase in the content of cardiac troponins (if it is impossible to determine - MV-CPK) in the blood; hemodynamic instability (arterial hypotension, congestive heart failure); paroxysmal ventricular disturbances of heart rhythm (ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation); early post-infarction angina. Signs of a low immediate risk of death and development of MI are:

absence of repeated attacks of chest pain; absence of depression or elevation of the ST segment - changes only in the T wave (inversion, decrease in amplitude) or normal ECG; no increase in the content of cardiac troponins (if it is impossible to determine them - MV-CPK) in the blood.

to perform a stress test 3–5 days after an episode with ACS symptoms

.

In patients with a high immediate risk of developing MI and death, conducting a stress test to assess the prognosis and determine treatment tactics is considered possible no earlier than 5–7 days after stable stabilization of the condition. If silent myocardial ischemia is suspected, a stress test should be preceded by Holter ECG monitoring. A standard stress test involves recording an ECG during physical activity on a bicycle ergometer or treadmill. In some patients, the exercise test may not be informative enough. In these cases, it is possible to perform stress echocardiography with physical activity

. Pharmacological stress tests using echocardiography or myocardial scintigraphy are indicated in patients who have limitations in physical activity.

The criteria for a high risk of an unfavorable outcome, determined by the results of stress tests, include: the development of myocardial ischemia with low tolerance to physical activity; extensive stress-induced perfusion defect; multiple stress-induced small perfusion defects; severe left ventricular dysfunction (ejection fraction less than 35%) at rest or during exercise; stable or stress-induced perfusion defect in combination with left ventricular dilatation.

Patients classified as high risk based on clinical signs, instrumental and laboratory tests, as well as patients with UA who have previously undergone coronary balloon angioplasty (CBA) or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) are indicated for coronary angiography.

. The results of the latter are the basis for the choice of further treatment tactics for the patient - in particular, assessing the feasibility of performing and determining the type of myocardial revascularization operation. In patients with persistently recurrent pain syndrome and severe hemodynamic instability, coronary angiography is recommended to be performed as soon as possible after the onset of clinical symptoms of ACS without prior stress tests.

Drug treatment

Taking into account ideas about the mechanisms of development, the main direction of pathogenetic therapy for ACS should be considered the effect on the blood coagulation system

. The drugs that influence the process of thrombus formation include three groups of drugs: thrombolytics, anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents.

Thrombolytic therapy (TLT)

The indication for TLT is anginal pain lasting more than 30 minutes, persisting despite taking nitroglycerin, in combination with an elevation of 1 mm or more in the ST segment in at least 2 adjacent ECG leads or the appearance of a complete block of the left bundle branch. Analysis of the results of placebo-controlled studies (GISSI-1, ISIS-2, ASSET, LATE) showed that TLT performed in the first 6 hours after the onset of clinical symptoms of developing MI reduces mortality during the first month after the development of MI by an average of 30% . Carrying out TLT within 6–12 hours from the onset of anginal pain reduces mortality by an average of 20% and is considered acceptable in the presence of clinical and ECG signs of expansion of the zone of myocardial necrosis. TLT performed later than 12 hours from the onset of MI does not have a positive effect on mortality. In the absence of persistent ST segment elevation, which is considered a sign of blockage of the coronary artery by a fibrin-containing thrombus, the use of TLT is also inappropriate.

Absolute contraindications to TLT are a history of hemorrhagic stroke, ischemic stroke or dynamic cerebrovascular accident within the last year, intracranial tumor, active internal bleeding, dissecting aortic aneurysm.

GUSTO Study

alteplase

administration is the best thrombolytic therapy strategy currently available for patients with MI.

The scheme for accelerated administration of alteplase (100 mg) for MI within 6 hours from the onset of symptoms with a body weight of more than 65 kg is as follows: 15 mg alteplase bolus over 1-2 minutes, then 50 mg intravenous infusion over 30 minutes. and then 35 mg over 60 minutes. Before starting, intravenous administration of heparin 5000 IU + intravenous infusion of heparin 1000 IU/hour in the next two days.

Anticoagulants

Of the compounds belonging to this pharmacological group, unfractionated heparin is mainly used in the treatment of patients with ACS.

(NFG). Unlike thrombolytic agents, UFH is administered not only to patients with persistent ST segment elevation, but also to patients with other types of ACS. The main contraindications to heparin therapy are active bleeding and diseases accompanied by a high risk of its occurrence.

The regimen for administering UFH to patients with ACS without persistent ST segment elevation: intravenous – bolus 60–80 U/kg (but not more than 5000 U), then infusion 12–18 U/kg/h (but not more than 1250 U/kg/h) within 48 hours. The optimal rate of heparin administration is determined by the value of the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT). The use of blood clotting time for this purpose is not recommended. A condition for the effectiveness of heparin therapy is considered to be an increase in aPTT by 1.5–2.5 times compared to the normal value of this indicator for the laboratory of a given medical institution. APTT is recommended to be determined 6 hours after the start of the infusion and then 6 hours after each change in the rate of heparin administration. If the APTT remains within the desired range after two consecutive determinations, the next analysis can be performed 24 hours later. Determining APTT before starting heparin therapy is not necessary.

In cases of ACS with persistent ST segment elevation, in the absence of contraindications, heparin is indicated for all patients who have not received TLT, as well as for patients who are scheduled for myocardial revascularization. UFH is recommended to be administered subcutaneously at 7500–12500 units 2 times a day or intravenously. The recommended duration of heparin therapy when administered subcutaneously is 3–7 days. The intravenous route of administration of UFH is preferable for patients with an increased risk of thromboembolic complications (extensive MI, anterior localization of MI, atrial fibrillation, history of thromboembolism, documented thrombus in the left ventricle).

The advisability of using UFH in combination with TLT is disputed. According to modern concepts, if thrombolysis is carried out with nonspecific fibrinolytic drugs (streptokinase, anistreplase, urokinase) against the background of the use of acetylsalicylic acid in a full dose, the administration of heparin is not necessary. When using alteplase, intravenous heparin is considered justified. Heparin is administered intravenously as a bolus of 60 units/kg (but not more than 4000 units), then at a rate of 12 units/kg/h (but not more than 1000 units/kg/h) for 48 hours under the control of aPTT, which should exceed the control level 1.5–2 times. It is recommended to start heparin therapy simultaneously with the administration of alteplase. The presence of criteria for a high risk of developing thromboembolic complications is considered as an indication for heparin therapy in patients who underwent thrombolysis, regardless of the type of thrombolytic drug.

Low molecular weight heparins (enoxaparin, fraxiparin) have a number of advantages over UFH: these drugs have a longer duration of action and a more predictable anticoagulant effect, are administered subcutaneously in a fixed dose, without requiring the use of an infusion pump and laboratory control. FRIC Research Results

,

FRAXIS

,

TIMI 11B

showed that low molecular weight heparins have no less, but no greater, ability than UFH to reduce the risk of MI and death in patients with UA and non-Q wave MI. Only enoxaparin, according to the

ESSENCE

, is stronger than UFH reduced the risk of developing the total number of “coronary events” (death, MI, recurrent angina) and the frequency of emergency myocardial revascularization operations. The combined results of the ESSENCE and TIMI 11B studies confirmed the clinical benefits of enoxaparin over UFH. The duration of treatment of patients with ACS with low molecular weight heparins is on average 5–7 days. The FRIC, FRAXIS and TIMI 11B studies showed that longer use did not lead to an additional reduction in the incidence of coronary events, but increased the risk of bleeding. However, the results obtained in the TIMI 11B and FRISC II studies suggest that increasing the duration of heparin therapy may be beneficial for patients preparing for myocardial revascularization surgery.

The cost of low molecular weight heparins exceeds the cost of UFH. At the same time, their effective clinical use does not require expensive instrumental and laboratory support. If a medical institution does not have the necessary material and technical resources and is not able to provide the administration of UFH in accordance with the requirements stated above, it is recommended to use low molecular weight heparins for the treatment of patients with ACS.

In recent years, 4 large studies have been carried out (OASIS-2, ASPECT, APRICOT-2, WARIS), the results of which suggest that the prognosis of patients who have suffered ACS can be significantly improved by including the indirect anticoagulant warfarin in complex therapy. Long-term (from 3 months to 4 years) use of warfarin (in addition to acetylsalicylic acid) helped to reduce the frequency of reocclusions of the infarct-related coronary artery in patients with MI after successful TLT, reducing the risk of developing MI, cerebral stroke and death without a significant increase in the frequency of hemorrhagic complications. However, the widespread use of warfarin in the secondary prevention of coronary artery disease is limited by the need for regular monitoring of the anticoagulation effect based on the international normalized ratio.

Antiplatelet agents

The most widely used antiplatelet agent in clinical practice is acetylsalicylic acid. The drug is indicated for all types of ACS. Its use clearly reduces the risk of death and MI. Thus, according to the ISIS II study, within 35 days after the development of MI, compared with the group of patients receiving placebo, mortality in treatment with acetylsalicylic acid alone decreased by 23%, with streptokinase alone - by 25%, and acetylsalicylic acid in combination with streptokinase - by 42%. The minimum dose of acetylsalicylic acid that reduces the risk of death and MI in patients with NS is 75 mg/day.

Among the contraindications to the use of acetylsalicylic acid in clinical practice, the most common are exacerbation of peptic ulcer disease, hemorrhagic diathesis and hypersensitivity to salicylates. In cases of intolerance to acetylsalicylic acid, the use of drugs from the thienopyridine group (ticlopidine, clopidogrel) is recommended. Their main disadvantage is the slow development of the antiaggregation effect. In case of ACS, in order to accelerate the development of drug effects in the first two days of therapy, it is allowed to increase the dose of ticlopidine to 1000 mg/day, followed by a transition to the standard dose of 500 mg/day. In cases of individual intolerance or the development of side effects (allergic reactions, gastrointestinal disorders, neutropenia), ticlopidine can be replaced with clopidogrel - 300 mg once, then 75 mg/day.

The concept of combined antiplatelet therapy, that is, a simultaneous blocking effect on various pathways of platelet activation, is considered very promising. In the CURE

It has been shown that treatment of patients who have undergone non-ST segment elevation ACS with a combination of acetylsalicylic acid and clopidogrel compared with therapy with acetylsalicylic acid alone leads to a significantly more pronounced reduction in the risk of developing cardiovascular events with no difference in the number of life-threatening bleedings.

Blockers of IIb/IIIa platelet receptors have the strongest antiaggregation effect

(abciximab, eptifibatide, tirofiban, lamifiban), which are able to block platelet aggregation caused by any physiological inducer. According to numerous studies (EPILOG, EPISTENT, EPIC, CAPTURE, PRISM–PLUS, PURSUIT, PARAGON, etc.), intravenous administration of these drugs to patients with ACS without ST segment elevation in addition to acetylsalicylic acid and UFH significantly improved the results of CBA both in combination , and without combination with stent installation. Abciximab was effective only in patients who underwent myocardial revascularization, tirofiban and eptifibatide, both during revascularization and during medical treatment. Additional reductions in adverse outcomes were particularly pronounced when glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor antagonists were added to standard antithrombotic treatment in patients with elevated cardiac troponin levels. At the same time, long-term oral use of these drugs, according to the OPUS-TIMI and SYMPHONY studies, did not have a positive effect on the results of treatment of patients with ACS. The main indication for the use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor antagonists in patients with ACS is the absence of persistent ST segment elevation in combination with a high immediate risk of death or the development of MI during a planned myocardial revascularization procedure in the next 24 hours.

Recommended doses of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor antagonists: abciximab - intravenous bolus of 0.25 mg/kg followed by infusion of 0.125 mcg/kg/min for 12–24 hours; eptifibatide – intravenous bolus of 180 mg/kg followed by infusion of 2.0 mcg/kg/min for 72–96 hours; tirofiban - intravenous infusion of 0.4 mcg/kg/min over half an hour, then 0.1 mcg/kg/min for 48–96 hours.

Nitrates

At the initial stage of treatment of patients with ACS, nitroglycerin and isosorbide dinitrate preparations are used intravenously. The initial infusion rate is 10 mcg/min. Every 3–5 minutes, the injection rate is increased by 10 mcg/min. The choice of infusion rate and rate of increase is determined by changes in the severity of pain and blood pressure (BP) levels. It is not recommended to reduce systolic blood pressure by more than 15% of baseline in normotension and by 25% in hypertension. When the desired effect is achieved, the infusion rate stabilizes and then gradually decreases. In case of excessive reduction in blood pressure, the duration of drug administration at each dosage step and the intervals between them increase. In addition to lowering blood pressure, the most common side effect that interferes with effective antianginal therapy is headache. After completion of intravenous administration, organic nitrate preparations (preferably isosorbide dinitrate or isosorbide 5-mononitrate derivatives) are administered orally according to an asymmetric scheme, ensuring a “nitrate-free” interval.

b-blockers

Drugs of this group are recommended for use in all patients with ACS in the absence of contraindications, which include bronchial asthma, severe obstructive respiratory failure, bradycardia at rest less than 50 beats per minute, sick sinus syndrome, atrioventricular block II-III degree, chronic heart failure IV functional class, severe arterial hypotension. It is preferable to start treatment with intravenous administration of beta-blockers with constant ECG monitoring

. After intravenous infusion, it is recommended to continue treatment with beta-blockers by oral administration. According to a meta-analysis of studies performed to date, long-term treatment with beta-blockers in patients who have had a Q-wave MI can reduce mortality by 20%, the risk of sudden death by 34%, and the incidence of non-fatal MI by 27%. B1-selective compounds without their own sympathomimetic activity are considered the most effective and safe.

Application regimens: propranolol

– intravenously slowly 0.5–1.0 mg, then orally 40–80 mg every 6 hours;

metoprolol

- intravenously 5 mg over 1-2 minutes three times with intervals between injections of 5 minutes, then (15 minutes after the last injection) orally 25-50 mg every 6 hours;

atenolol

- intravenously 5 mg over 1-2 minutes twice with an interval between injections of 5 minutes, then (1-3 hours after the last injection) orally 50-100 mg 1-2 times a day. The individual dose of beta-blockers is selected taking into account the heart rate, the target value of which is 50–60 beats per minute.

Calcium antagonists

Derivatives of dihydropyridine, benzodiazepine and phenylalkylamine, the most widely used representatives of which are first-generation drugs - nifedipine, diltiazem and verapamil, respectively, differ in the severity of vasodilating effects, negative inotropic and negative dromotropic effects. Meta-analyses of the results of randomized trials revealed a dose-dependent negative effect of short-acting nifedipine on the risk of death in patients with UA and MI. In this regard, short-acting dihydropyridine derivatives are not recommended for the treatment of patients with ACS. At the same time, according to some studies, long-term use of diltiazem (MDPIT, DRS) and verapamil (DAVIT II) prevents the development of recurrent MI and death in patients who have had an MI without a Q wave. In patients with ACS, diltiazem and verapamil are used in cases when there are contraindications to the use of beta-blockers (for example, obstructive bronchitis), but in the absence of left ventricular dysfunction and atrioventricular conduction disorders. Recommended doses of drugs are 180–360 mg/day.

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors

The positive effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors on the survival of patients who have had myocardial infarction (especially complicated by congestive heart failure) has been proven in a number of controlled studies - GISSI-3

,

ISIS-4

,

AIRE

,

SAVE

,

TRACE

, etc. Extensive MI with a pathological Q wave is an indication for the use of ACE inhibitors even in the absence of clinical and echocardiographic signs of left ventricular dysfunction. The earlier treatment with ACE inhibitors begins, the more pronounced their inhibitory effect on the process of post-infarction cardiac remodeling. On the other hand, as shown by the results of the CONSENSUS II study, which was interrupted early due to the fact that mortality in the group of patients receiving enalapril exceeded mortality in patients in the control group, ACE inhibitors should be used in the treatment of patients with MI with great caution. If possible, therapy should be started after hemodynamic stabilization in the first 48 hours from the onset of MI. The following initial doses of drugs are recommended: captopril - 25 mg/day, enalapril and lisinopril - 2.5 mg/day, perindopril - 2 mg/day. The dose should be increased gradually under the control of blood pressure and renal function. Once the optimal dose is reached, therapy should be continued for many years.

Non-drug treatment

CBA or CABG is performed in patients with recurrent myocardial ischemia to prevent MI and death. The choice of myocardial revascularization method depends on the degree, extent and localization of coronary artery stenosis, the number of affected vessels, which are determined based on the results of angiography. CABG surgery for UA and in the acute period of MI is associated with an increased risk of operative mortality. This technique of myocardial revascularization is justified in cases of damage to the trunk of the left coronary artery or multivessel disease. In patients with damage to one, or less often two vessels, myocardial revascularization is usually achieved by CBA.

As stated above, improvement in the results of CBA, as well as the coronary artery stenting procedure (EPISTENT study), can be achieved using IIb/IIIa receptor blockers. CBA is increasingly used in the treatment of patients with ST segment elevation instead of TLT. This allows not only to obtain an additional reduction in hospital mortality, but also to significantly reduce the risk of complications caused by drug effects on the blood coagulation system.

Tactics of medical care for patients with ACS

The scope of instrumental and laboratory tests, as well as the choice of methods of drug and non-drug treatment of a patient with ACS symptoms is determined by the conditions of medical care and the capabilities of a particular medical institution. A preliminary diagnosis is established based on the patient’s complaints. It should be emphasized that the absence of pathological changes on the ECG does not exclude ACS. If a connection between chest pain and acute coronary insufficiency is suspected, the patient should be urgently hospitalized - if possible, in a specialized department (ward) of intensive observation and therapy, where the necessary diagnostic tests are performed.

The algorithm for medical care for patients with ACS is presented in Figure 2. The first medications that should be used if ACS is suspected are acetylsalicylic acid - 325 mg orally (to speed up absorption, the tablet should be chewed) and nitroglycerin - 0.5 mg sublingually (if necessary You can take up to 3 tablets with an interval of 5 minutes). Patients with persistent ST segment elevation or the appearance of left bundle branch block receive TLT or undergo primary CBA. Patients with ST segment depression, T wave inversion or no ECG changes receive heparin therapy, beta-blockers, and if pain persists, intravenous nitrates. In cases of intolerance to beta-blockers or the presence of contraindications to their use, calcium antagonists are prescribed. All patients are provided with multichannel ECG monitoring. After receiving additional information (the results of clinical observation, ECG data in dynamics, analysis of the content of cardiac troponins, CPK and MB-CPK in the blood), the diagnosis is clarified and the risk of negative developments is assessed, on the basis of which further tactical decisions are made. Patients who have developed MI, but have not undergone CBA in the acute period, undergo an exercise test before discharge from the hospital to determine the prognosis and indications for surgical treatment.

Rice. 2. Algorithm of medical care for patients with ACS

Patients with a high immediate risk of developing MI and death, if possible, should begin IIb/IIIa receptor blockers, undergo coronary angiography, CBA, and continue therapy with IIb/IIIa receptor blockers. In cases where the administration of drugs of this group and the procedure for myocardial revascularization is impossible, heparin therapy (UFH or low molecular weight heparins) is carried out in combination with acetylsalicylic acid, beta-blockers and, if necessary, nitrates intravenously. After stabilization of the condition of this category of patients, a test with physical activity is indicated to determine the prognosis and indications for CBA or CABG. Treatment of patients at low risk of developing MI and death includes oral acetylsalicylic acid, beta-blockers or calcium antagonists and nitrates. In the absence of ECG changes and an increase in the blood level of biochemical markers of myocardial necrosis according to the results of two determinations, the administration of UFH or low molecular weight heparins can be discontinued. After 5–7 days, patients in this category are advised to perform an exercise test to clarify the diagnosis of coronary artery disease, prognosis and further treatment tactics.

Most adverse events occur in the first months after the development of ACS. In the treatment of patients who have suffered an ACS, in addition to the means of directly influencing the coronary circulation, it is necessary to carry out measures aimed at weakening the effect of modifiable risk factors for the progression of coronary artery disease. Patients should stop smoking. In cases where the use of beta-blockers or calcium antagonists and ACE inhibitors in moderate therapeutic doses does not correct high blood pressure, the doses of the drugs used should be increased or additional antihypertensive drugs should be prescribed. Patients should follow a lipid-lowering diet. Statins, according to modern concepts, are indicated for patients who have undergone ACS, even in the absence of an increase in the level of atherogenic low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in the blood. The idea of using statins from the first day of the disease is receiving more and more compelling evidence.

Mortality rates for ACS in Russia are 2–3 times higher than in Western Europe and North America. The main reason for this difference is the inadequate application of effective methods for diagnosing and treating ACS in domestic clinical practice. Unfortunately, many healthcare institutions in modern Russia do not have the ability to ensure compliance with recommendations for medical care for patients with ACS. However, along with objective difficulties (primarily financial ones), the reasons for this include the lack of professional awareness of doctors. It is the lack of professional knowledge that is the prerequisite for the irrational use of financial resources allocated to provide medical care to patients with ACS, a significant part of which is currently spent on providing uninformative diagnostic techniques and purchasing ineffective drugs. Acceptance by physicians of the main provisions of the recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of ACS is the most important condition for their successful implementation in clinical practice, and the implementation of agreed standards represents a proven opportunity to significantly improve the results of medical care.

St. Petersburg State Medical Academy named after.

I.I. Mechnikova References:

1. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with acute myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Pratice Guidelines (Committee on Management of Acute Myocardial Infarction). J Am Coll Cardiol 1996;28:1328–1428.

2. Update: ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with acute myocardial infarction: executive summary and recommendations: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Pratice Guidelines (Committee on Management of Acute Myocardial Infarction). Circulation 1999;100:1016–1030.

3. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina and non–ST–segment elevation myocardial infarction. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Pratice Guidelines (Committee on the Management of Patients with Unstable Angina). J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;36:970–1062.

4. Management of acute coronary syndromes: acute coronary syndromes without persistent ST segment elevation. Recommendations of the Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2000;21:1406–1432.

5. Treatment of acute coronary syndrome without persistent ST segment elevations on the ECG. Russian recommendations. Developed by the Committee of Experts of the All-Russian Scientific Society of Cardiologists. M 2001;23.