General information

Infectious and inflammatory diseases in newborns are quite common. This is not explained by the perfection of defense mechanisms in this period. The most pronounced deficiency of immunity and immaturity of the barrier function of the skin are in premature infants, in whom purulent-inflammatory diseases account for 80% of all diseases of the newborn period. Most diseases are minor infections: omphalitis , pustular rashes , otitis , dacryocystitis (inflammation of the lacrimal sac).

Omphalitis (ICD-10 code P38) is an inflammatory process of the bottom of the umbilical wound, skin and subcutaneous tissue of the navel and umbilical ring. Depending on the form of omphalitis, the umbilical vessels and deeper layers of the skin may be involved in the process. This disease refers to acquired navel diseases that occur when normal care for a newborn is disrupted.

To prevent infection of the umbilical cord, it must be clean and should not be exposed to feces or urine. The umbilical cord residue disappears by the end of the second week and, if this does not happen, omphalitis may develop. Some authors are of the opinion that infection occurs before the birth of the child (with premature rupture of the membranes) and at the time of passage through the birth canal. Some congenital pathologies of the navel, which will be discussed in this article, also lead to inflammation of the peri-umbilical area. In the future, a person is constantly in contact with many microorganisms from the external environment, which does not exclude (under certain conditions) the development of this disease in adults. Of no small importance in this are congenital anomalies of the umbilical region, which were not detected in childhood and did not manifest themselves for a long time in adulthood.

Symptoms of navel inflammation in adults

The development of a purulent process in adults can be suspected based on the following signs:

- the skin turns red, inflammation begins, and over time purulent discharge is noticeable;

- the navel tissues were damaged some time before the development of signs of inflammation - by piercing, accidental blow, punctures;

- with poor hygiene, the development of omphalitis is possible;

- if there are sutures nearby and they begin to become inflamed, the process may spread to the umbilical area.

Symptoms can be divided depending on the form of pathology. Catarrhal omphalitis develops as follows:

- body temperature remains within acceptable limits;

- redness of the umbilical ring is observed;

- the patient’s health remains normal;

- from time to time a light crust appears on the navel, under which new connective tissue forms;

- blood tests remain clear.

Local treatment for simple omphalitis is highly effective. However, with purulent inflammation the situation becomes more complicated:

- the umbilical ring becomes very red, and the temperature can rise to 39 degrees;

- the crust on the navel becomes black and mobile;

- yellow, cloudy or white discharge appears from under it;

- in almost all cases an unpleasant odor develops.

In this case, blood tests can reveal an increased number of leukocytes.

You should not wait for symptoms of inflammation of the umbilical region to develop, otherwise this can lead to dangerous complications. When the first signs appear, get tested.

Pathogenesis

The pathogen penetrates the tissues surrounding the navel in different ways (through the placenta or umbilical cord stump) and causes catarrhal, purulent or even necrotic inflammation. The infection spreads to the umbilical vessels, causing an inflammatory process in them ( phlebitis , arteritis ). The incidence of phlebitis in newborns increases with catheterization of the umbilical vein for infusion therapy.

The spread of inflammation leads to the development of phlegmon in the umbilical area. The infectious process in thrombophlebitis of the umbilical vein spreads along the portal vein to the intrahepatic branches of the portal vein - purulent foci are formed along the veins, despite the fact that the umbilical wound may have healed by this time.

Pathogenesis of the disease in adults

In newborns, purulent-septic inflammation of the navel ranks first in the structure of morbidity at 1 month of life. However, in adults, the pathology is extremely rare and is always complicated by previous injuries or illnesses. This is a striking local process that is not accompanied by general septic manifestations.

Umbilical infections are caused by staphylococci and streptococci, as well as E. coli, pneumococci and diphtheria bacilli (but much less frequently than the first 2 bacteria). The disease develops after the pathogen penetrates through the tissues adjacent to the navel, through wounds, damaged blood vessels and foci of inflammation.

Cellulitis forms in the navel area. If the umbilical vein is drawn into the process, phlebitis develops. It can spread to the portal vein, leading to the formation of purulent foci after the main wound has healed.

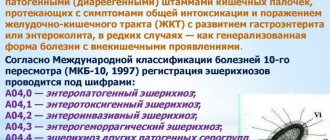

Classification

Inflammation of the navel does not have a generally accepted classification, however, based on clinical data, the following forms are distinguished:

- catarrhal (wetting navel);

- purulent;

- phlegmonous;

- necrotic.

If the umbilical vessels are affected, phlebitis and arteritis occur.

Most often this pathology occurs in children. However, inflammation of the navel in adults also occurs and the reasons for this are:

- Infection due to poor hygiene and skin trauma.

- Navel fistulas.

- Thrombophlebitis of the umbilical vein.

- Endometriosis of the navel.

- Inflammation of the urachal cyst. The urachus is the urinary duct in the embryo that connects the top of the bladder and the umbilicus. A uruchus cyst is a non-occlusion of the middle part of the urinary duct. In adults, the urachus is represented by a fibrous cord that connects the bladder and the umbilicus.

If a woman's navel gets wet, this is not the norm. The scar at the site of the fallen umbilical cord should always be dry and not cause any discomfort in the woman. If there is pain, an unpleasant odor and redness, these are signs of inflammation. If the navel is red and wet, first of all you need to suspect omphalitis in adults and consult a surgeon.

Catarrhal omphalitis occurs with serous discharge from the navel, slight redness of the skin inside the navel and the umbilical ring itself occurs. Usually, thorough treatment of the cavity with antiseptics ( hydrogen peroxide , Chlorhexidine , Miramistin ) and antibiotic ointments ( Levomekol , Levosin ) give a quick positive result.

In the absence of treatment and a decrease in the protective properties of the body, the inflammatory process progresses and purulent omphalitis develops.

At the same time, the swelling and redness of the navel ring increases, inflammation of the fatty tissue becomes pronounced and pus appears in the navel. Phlegmonous omphalitis is manifested by severe inflammation around the umbilical ring, swelling and protrusion of the navel area. The resulting abscess leads to phlegmon of the abdominal wall. With this form, veins and arteries are involved - the umbilical vessels are thickened, painful and easily palpable. The vessels of the anterior abdominal wall dilate, the umbilical region bulges, and the skin around the navel is significantly hyperemic.

The necrotic form of omphalitis is a fairly rare complication of the phlegmonous form in severely weakened and premature children. The skin in this form becomes purple-bluish, skin necrosis and detachment from the underlying tissues occur. In a large wound, the muscles of the abdominal wall and fascia are exposed, which undergo purulent melting. Intestinal prolapse may also occur through the resulting muscle defect. This form is the most severe and ends with the development of sepsis .

One of the causes of navel inflammation is pathology of the urachus (urinary duct), which is more often diagnosed in newborns and occurs in 30-50% of children. The urinary duct must close at certain times during the embryonic period. Malformations of the urachus, depending on the degree of nonfusion, are divided into: umbilical fistula, urachus cyst, vesico-umbilical fistula and bladder diverticulum. Of all the possible anomalies of the urachus, the most common are urachus cyst and umbilical fistula.

Umbilical fistula is most often a congenital pathology and is detected immediately after birth. The urinary duct connecting the navel with the upper part of the bladder should normally close by 5-6 months of fetal development. Sometimes the lumen of the urachus remains throughout life and in this case a vesico-umbilical fistula (ICD-10 code Q64.4. Anomaly of the urinary duct) or a cyst is formed. With a fistula, urine acts as the discharge. The skin around it becomes inflamed and irritated by the discharge. When examining with a probe, a pocket is identified in the direction of the bladder. A fistula develops not only when the urinary duct is not closed, but also the vitelline-intestinal duct. When the vitelline-intestinal duct is not closed, an intestinal-umbilical fistula is formed and then the discharge can be intestinal or mucous. In rare cases, the intestinal mucosa or, much less frequently, the omentum emerges through this fistulous tract.

An acquired umbilical fistula is formed after a long inflammatory process, localized on the anterior wall of the abdomen, if an abscess . Urachal pathology in adults often does not manifest itself and is an incidental finding during cystoscopy and cystography .

Only a suppurating urachal cyst can manifest itself. In the case of congenital and acquired fistula, treatment is surgical - excision of the fistula and suturing of existing defects in the wall of the intestine or bladder. In the presence of an umbilical fistula, conservative therapy is possible at first in the hope of complete fusion of the duct.

Urachal cysts manifest themselves during inflammation and suppuration. A suppurating cyst can form a fistulous tract and pus will come out, and its amount increases with palpation below the navel. If a suppurating urachal cyst communicates with the bladder, cystitis . peritonitis occurs , and suppuration is complicated by phlegmon of the anterior abdominal wall . Both conditions are extremely severe.

Causes of omphalitis (wet navel)

Among the pathogens that cause omphalitis are staphylococci, streptococci , Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Proteus. In 47-80% of cases, the development of the disease is caused by associations of microorganisms. Anaerobes (clostridia, bacteroides and others) cause gangrene of the umbilical cord.

If we consider the causes of a weeping navel in an adult, the main ones include:

- Mechanical injuries to this area (piercing and improper care after piercing).

- Irritation of the umbilical ring by clothing, buttons, buckles, and rough fabrics.

- Purulent skin diseases.

- Scratching.

- Poorly performed hygiene procedures.

- Deep and knotty navel.

- Fistulas of the umbilical region.

- Inflamed postoperative sutures and punctures of the umbilical ring.

- Diabetes.

- Metabolic disorders.

- Obesity.

Why does a woman's navel get wet? This place is a accumulation of opportunistic microbes, and with excess weight, excessive sweating and other provoking factors, they cause inflammation. Improper hygiene and microtrauma of the skin most often cause first weeping and then severe inflammation.

After taking a shower, you need to moisten a cotton swab with shampoo and rub it well inside the navel. After this, dry using a dry cotton swab and apply moisturizer. Lack of proper disinfection after piercing, which is often done by women, is also a cause of weeping. Perhaps the woman had laparoscopic surgery, and the access point was the navel. In this case, it is necessary to exclude the presence of a fistula, which often forms after laparoscopic surgery. If all of the above factors are excluded, then this phenomenon can still be observed with umbilical fistulas - with a patent urinary or vitelline duct.

The causes of a weeping navel in newborns are most often an infection (intrauterine or acquired after birth):

- Streptococcal infection. Diseases caused by group B streptococcus are the most common perinatal infections. This pathogen causes minor forms of intrauterine infections ( sinusitis , conjunctivitis , otitis , osteomyelitis , omphalitis , skin lesions) and severe forms ( meningitis , sepsis , encephalitis , pneumonia ).

- Chlamydia . Pregnancy with chlamydia is dangerous due to intrauterine infection of the fetus, and in the early neonatal period, along with conjunctivitis and pneumonia typical of chlamydial infection, chlamydial omphalitis also occurs in newborns.

Among the congenital pathologies of the newborn period that cause weeping in this area, it is worth noting the non-closure of the ducts (urinary and vitelline-intestinal). This pathology is also caused by medical procedures: catheterization of the umbilical veins and ligation of the umbilical cord. Of primary importance is improper care of the umbilical cord remnant: its complete absence or the use of alcohol-containing treatment products, which contribute to drying of the skin and the formation of “pockets”.

Symptoms

Symptoms depend on the form of the disease. The catarrhal form is manifested by mild redness and the release of serous fluid from the wound, on the surface of which a light crust forms. There is usually no pain or swelling in the navel area. The temperature of a child or adult is normal and general health does not change. Purulent inflammation is severe: pronounced hyperemia of the umbilical ring appears, an unpleasant odor appears, and pus is separated from the navel with a viscous consistency. Body temperature in young children rises to 38-39°C; in adults it can be low-grade. The vessels are palpated above or below the navel as elastic cords.

The phlegmonous form is characterized by rapid development of inflammation around the navel and the formation of abscesses. The umbilical wound in newborns becomes covered with a dirty coating, and its bottom becomes loose and deep, periodically bleeding ulcers appear. The tissues around the wound are sharply swollen and the local temperature is elevated. Swelling of the skin can affect not only the abdominal area, but also the chest. Hyperemia quickly spreads and moves to the abdominal area. The process very quickly spreads beyond the umbilical wound through the blood and lymphatic vessels. At a considerable distance from the wound, purulent discharges (abscesses) develop. Lymph nodes are enlarged.

The necrotic form is the most severe form, which is a complication of catarrhal. It is characterized by severe redness of the skin and damage to all layers of the dermis. The skin in this form becomes purple-bluish, skin necrosis and detachment from the underlying tissues develop. In a large wound, the muscles of the abdominal wall and fascia are exposed, which undergo purulent melting. Intestinal prolapse may also occur through the resulting muscle defect. If left untreated, this form develops into a septic process. It is the last two forms that are the main cause of purulent-septic diseases in infants - sepsis , osteomyelitis and others. Treatment of all forms will be discussed in the appropriate section.

Tests and diagnostics

The diagnosis is established upon examination of the patient: the presence of serous or purulent inflammation of the umbilical wound, swelling and hyperemia of the umbilical ring, tenderness of the umbilical vessels, delayed epithelization of the wound.

Laboratory tests include:

- Blood test - leukocytosis is determined with a shift in the leukocyte formula to the left and an increase in ESR.

- Sowing the discharge from the wound to determine the pathogens.

- Blood culture to determine the sensitivity of microflora to antibiotics.

- In case of phlegmonous or necrotic form - ultrasound of internal organs.

Instrumental research. The wound is probed to exclude umbilical fistulas. A test is also performed with a solution of methylene blue , which is injected into the fistula and the appearance of the drug in the urine or feces is observed (they become blue).

Diagnosis of omphalitis

A specialist can easily make a diagnosis even from the first symptoms of omphalitis, but to clarify the form, tests will be required, the main one of which is a laboratory examination of blood counts. If you have omphalitis, you can contact a therapist or surgeon. To exclude complications, additional diagnostic methods may be prescribed:

- Ultrasound of the abdominal cavity - to ensure that there are no purulent foci on the abdominal wall;

- x-ray of the peritoneum;

- Ultrasound of soft tissues.

Hospitalization for adults is required in rare cases - only when there is a complication of the underlying disease that caused omphalitis.

Omphalitis in newborns

The presence of microbial associations in the cultures of a pregnant and parturient woman significantly increases the risk of severe intrauterine infections: otitis media , inflammation of the navel in newborns, conjunctivitis , as well as purulent complications. The severity of the newborn's condition and complications of infections depend on the age of the newborn - they are more severe in premature infants. The physiological characteristics of the baby's skin, the presence of an umbilical cord and an umbilical wound - all this predisposes to the appearance of purulent-septic diseases if care is not taken care of. Diseases of the umbilical wound and umbilical cord remnant occupy first place among infectious and inflammatory diseases in infants. Until the umbilical wound is epithelialized, the risk of infection and even entry of the pathogen into the newborn’s blood through the umbilical vessels remains.

The most common form of the disease is catarrhal omphalitis , a condition where the navel of a newborn becomes wet. It usually begins in the second week of life and appears as a long-term non-healing wound with a slight serous discharge. Periodically, the wound becomes crusty. Slight local hyperemia (redness) and mild swelling of the umbilical ring are possible. The infiltration of fiber around the ring is insignificant, and an unpleasant odor may appear from the umbilical cord. Often granulations grow excessively in the wound and a protrusion is formed - navel fungus , resembling a mushroom in shape. The umbilical vessels are not identified. The baby's general condition is not affected and the body temperature is normal.

In the absence of proper care and treatment in weakened children, the process progresses and after a few days pus appears in the umbilical wound (pyorrhea), swelling and hyperemia of the umbilical ring becomes pronounced, and due to swelling of the tissue around the navel, it bulges above the surface of the abdomen. When purulent discharge appears, they speak of purulent omphalitis. The skin around the navel turns red, it becomes hot to the touch and the veins of the anterior abdominal wall may dilate. Red stripes extend from the navel, which indicates associated lymphangitis . The baby's condition worsens: he sucks poorly, becomes lethargic, and the temperature rises. Changes appear in the blood test (the number of leukocytes increases, the ESR increases).

Phlegmonous omphalitis in children occurs when inflammation spreads to surrounding tissues. Phlegmon of the anterior abdominal wall is manifested by severe swelling, widespread skin hyperemia and protrusion of the umbilical region. At the bottom of the wound in the navel, an ulcer may form, covered with fibrinous deposits. When pressing in the navel area, pus is released from the wound. Deterioration of the newborn's condition is noted: lethargy, weak sucking, high temperature, pale skin, regurgitation.

When an anaerobic infection is added, a necrotic form of the disease develops. This complication of the phlegmonous form is very rare in severely weakened and premature children. This form is characterized by the process spreading deeper and developing tissue necrosis. The umbilical cord remains dirty brown, moist and acquires a putrid odor. The skin is purplish-bluish, peels off and a large wound is formed. The process involves the muscles and fascia of the abdominal wall. It is possible that part of the intestine may prolapse through a defect formed by necrotic muscles. This form often leads to peritonitis and sepsis , which in itself is life-threatening for the newborn.

Navel fistula can be complete or incomplete. A complete fistula is formed when the duct between the intestinal loop (vitelline duct) and the navel is not closed or is preserved throughout the entire length of the urinary duct. If the vitelline duct is not closed, the child at birth will notice an abnormally thickened umbilical cord and an enlarged umbilical ring. The umbilical cord remnant does not fall off for a long time, and after it falls off, a fistula opening becomes visible in the center of the navel, from which intestinal contents are separated. The main manifestation of a complete fistula is prolonged weeping of the wound and release of intestinal contents (this does not always happen). If the fistula is wide, when the baby is restless, part of the intestine comes out and is compressed, which is accompanied by intestinal obstruction . If the urinary duct is not closed, an acidic discharge comes out of the umbilical wound. An incomplete umbilical fistula is formed if the fusion of the distal vitelline duct is disrupted. With incomplete fistulas, a picture of catarrhal omphalitis .

Typically, the length of the fistula tract is 2-3 cm. The diagnosis is confirmed by probing the tract: a special probe is inserted to a depth of 1-2 cm. The final examination of the navel in a newborn for fistulas involves performing a fistulography or a test with methylene blue. During fistulography, a radiopaque substance is poured into the fistula through a catheter. The amount of substance administered depends on the type of fistula. A water-soluble substance is injected into narrow passages. The substance is administered under X-ray television control and targeted radiographs are taken. At the end of fistulography, the substance is sucked out with a syringe, the fistula is washed with saline solution and a bandage is applied.

Umbilical cord care, prevention and treatment of omphalitis

- Zubkov Viktor Vasilievich

- Ryumina Irina Ivanovna

Neonatology: news, opinions, training.

2014. No. 1. P. 176-180. The umbilical cord, which connects the baby and the placenta in utero, consists of blood vessels and connective tissue covered with a membrane, which is washed by the amniotic fluid. After birth, the umbilical cord is cut and the baby is physically separated from the mother. Within 1-2 weeks of life, the umbilical cord remnant dries out (mummifies), the surface at the site of attachment of the umbilical cord epithelializes, and the dry remnant of the umbilical cord disappears. Until the umbilical cord falls off and the umbilical wound has not epithelialized, there remains a high probability of penetration of an infectious pathogen through the umbilical vessels into the child’s blood. However, the umbilical cord remnant cannot be sterile, since during normal childbirth and immediately after birth, the baby’s skin, including the umbilical cord, is colonized mainly by opportunistic microorganisms, such as coagulase-negative staphylococci and diphtheroids, as well as opportunistic bacteria , such as Escherichia coli and streptococci.

Cord cutting and umbilical cord care are procedures that have been known for a very long time, their technology varies depending on established practices and cultural characteristics. In many developing countries, the umbilical cord is cut with non-sterile instruments (a razor or scissors), and a variety of substances, such as charcoal, fat, cow dung or dried bananas, are still used to process the umbilical cord residue to speed up mummification and shedding. Such methods of cord care are a source of bacterial infection, including neonatal tetanus, which still occurs in developing countries and makes a significant contribution to neonatal mortality. The high mortality rate of newborns in developing countries from umbilical sepsis and the decrease in neonatal mortality in countries where the rules of asepsis and antisepsis have long been used for any manipulation of the umbilical cord, including in our country, prove that the basis for the prevention of omphalitis lies in the intersection of the umbilical cord and care behind the umbilical remnant with a sterile instrument and clean hands. However, there is still no consensus regarding the prevention of infectious pathology associated with the penetration of microorganisms through the vessels of the umbilical cord. Most often, alcohol, silver nitrate solution, iodine preparations, chlorhexidine, aniline dyes (gentian violet, acriflavine, brilliant green solution, etc.) are used for this purpose. Some countries recommend the use of topical antimicrobials, including bacitracin, neomycin, nitrofurans, or tetracycline, in the form of moisture-absorbing powders to speed up the mummification of the umbilical cord, in the form of an aqueous and alcoholic solution or ointment. There is also a practice of caring for the umbilical cord remnant without the use of antibacterial or disinfectants, keeping the umbilical cord remnant dry and clean. Bathing the baby immediately after birth with the addition of disinfectant solutions such as hexachlorophene was previously recommended as this may reduce skin colonization; however, hexachlorophene is absorbed through the skin and can be neurotoxic, so its use in neonatology practice is not currently recommended.

I. Technique for cutting the umbilical cord and processing the umbilical cord residue in the delivery room

The newborn is received in a sterile diaper. For initial treatment of a newborn, a sterile individual kit is used.

It is recommended to clamp and cut the umbilical cord 1 minute after birth.

It is considered safe to clamp the umbilical cord between 1 and 3 minutes after birth.

Early clamping of the umbilical cord (immediately after birth) can lead to low hemoglobin levels and the development of late anemia. At the same time, clamping the umbilical cord too late often leads to the development of hypervolemia and polycythemia, which can cause respiratory disorders and hyperbilirubinemia.

1. Cord clamping and cutting (IA):

— The umbilical cord is cut by a midwife in the maternity ward wearing sterile gloves.

— Place one Kocher clamp on the umbilical cord at a distance of 10 cm from the umbilical ring.

— Place the second Kocher clamp on the umbilical cord as close as possible to the external genitalia of the woman in labor.

— Place the third Kocher clamp 2 cm outward from the first.

— Wipe the area of the umbilical cord between the first and third Kocher clamps with a gauze ball moistened with a 95% ethyl alcohol solution and cut with sterile scissors.

2. Treatment of the umbilical cord:

Currently, the most reliable and safe is a disposable plastic clamp, which is applied to the umbilical cord.

A plastic clamp is applied to the umbilical cord by a midwife in the maternity ward in the delivery room after the baby is first applied to the breast.

Before applying a plastic staple (or ligature), staff perform hand hygiene. The area where the clamp is applied is treated with 70% ethyl alcohol.

3. Technique for applying a plastic clamp:

— Change gloves.

— Carry out hand hygiene.

— Wear sterile gloves.

- Using a sterile gauze pad, squeeze the blood from the umbilical ring to the periphery.

— Treat the umbilical cord area with a 70% ethyl alcohol solution using a sterile gauze pad.

— Place a plastic clamp on the umbilical cord at a distance of 2-3 cm, but not less than 1 cm from the umbilical ring. If the clamp is applied too close to the skin, abrasion of the skin of the umbilical ring may occur.

— After applying the clamp, cut off the umbilical cord tissue above the clamp, wipe off the blood with a sterile gauze pad.

— If it is necessary to remove the clamp, use special sterile forceps.

Not recommended:

applying a gauze bandage and re-processing the umbilical cord residue immediately after applying the clamp.

4. Caring for the umbilical cord (IA)

The umbilical cord residue undergoes natural mummification and spontaneous separation within 2 weeks. Final epithelization of the umbilical wound occurs within 3-4 weeks after birth.

When examining the umbilical cord on a daily basis, it is necessary to pay attention to the stages of natural separation of the umbilical cord:

- the umbilical cord dries out and decreases in volume;

-becomes denser;

- takes on a dark brown tint;

-separates from the child’s body;

- the bottom of the umbilical wound is covered with epithelium.

Recommended:

— Caring for the umbilical cord does not require the creation of sterile conditions.

— It is enough to keep the umbilical cord dry and clean, protect it from contamination with urine, feces, as well as from injury — avoid tight swaddling or the use of disposable diapers with a tight fit.

- In case of contamination (urine, feces), the umbilical cord and the skin around the umbilical ring should be washed with water and liquid soap used in the department and dried with a clean gauze cloth.

The timing of discharge from the obstetric hospital is determined by the state of health of the mother and child. From an epidemiological point of view, including in order to reduce the incidence of purulent-inflammatory diseases of the umbilical wound, early discharge on the 3-4th day after birth, including before the umbilical cord falls off, is justified. In other words, the discharge of a newborn home does not depend on the time of the umbilical cord remnant falling off.

Before discharge, the neonatologist consults the mother/parents on the care of the newborn, including skin care and umbilical cord care, with the appropriate note in the newborn’s medical documentation.

Not recommended:

-use bandages and additional tying of the umbilical cord to speed up the fall of the umbilical cord;

- treat the umbilical cord remnant with any antiseptics (solutions of aniline dyes, alcohol, potassium permanganate solution, etc.), since the local use of antiseptics not only does not reduce the frequency of infections, but also helps to delay the spontaneous falling off of the umbilical cord remnant.

— forcible removal (cutting off) of the umbilical cord is not recommended, since such a procedure can cause serious complications (bleeding, injury to the intestinal wall with an undiagnosed hernia of the umbilical cord, infection). The effectiveness of this procedure has not been proven, but the potential danger is obvious. Forced removal of the umbilical cord should be recognized as an unjustified invasive intervention, potentially dangerous to the life of the newborn.

II. Diagnosis and treatment of omphalitis (IB)

Omphalitis is an inflammatory process of the bottom of the umbilical wound, skin and subcutaneous tissue around the navel, and umbilical vessels.

Classification according to ICD X: R-38

Children who have been diagnosed with omphalitis, regardless of the form, should be transferred from the obstetric hospital to the pathology department of newborns and premature infants, and in severe cases of necrotizing omphalitis - to the neonatal surgery department.

Etiology:

the most common pathogens are bacteria -

gram-positive ( S. aureus

) and gram-negative (

E. coli, P. mirabilis, P. vulgaris, M. morganii), P. aeruginosa

, etc.

Clinical forms:

-simple omphalitis;

-phlegmonous omphalitis (diffuse purulent);

- necrotizing omphalitis.

Simple omphalitis:

The most common simple form (wet navel) is the most favorable prognostically (Fig. 1):

-local hyperemia;

-swelling of the umbilical (umbilical) ring;

-infiltration of subcutaneous fat around the umbilical ring;

- an umbilical wound that does not heal for a long time, from which there is serous or serous-purulent discharge;

- from time to time the umbilical wound becomes crusty; there is an unpleasant odor from the umbilical cord or discharge from the umbilical wound;

-possible excessive growth of granulating tissue, which leads to the formation of fungus;

- the general condition of the child does not suffer.

Phlegmonous omphalitis

(diffuse purulent) (Fig. 2): in addition to the symptoms described above, the following are noted:

-spread of the inflammatory process to surrounding tissues;

-hyperemia and skin infiltration in the navel area;

- umbilical wound in the form of an ulcer, covered with fibrinous deposits, surrounded by a dense skin cushion;

-discharge of pus from the umbilical wound when pressing on the peri-umbilical area;

- phlegmon of the anterior abdominal wall;

- deterioration of general condition, increase in intoxication, increase in body temperature.

Necrotizing omphalitis

observed in weakened children with the addition of an anaerobic infection (Fig. 3):

- necrosis of the skin and subcutaneous tissue (The necrotic process can cover all layers of the anterior abdominal wall and cause peritonitis);

- mummification of the umbilical cord remains stops, it becomes moist, acquires a dirty brown tint and an unpleasant putrefactive odor;

- a severe complication of phlegmonous and necrotizing forms of omphalitis is an ascending infection - thrombosis of the umbilical, portal veins, portal hypertension, liver abscesses and sepsis.

Treatment tactics for simple, phlegmonous and necrotic forms of omphalitis

1.

In order to control the detection, prompt (daily) registration of purulent-inflammatory diseases and including the implementation of anti-epidemic measures in the prescribed manner, the attending physician promptly brings information to the head of the department and the hospital epidemiologist (assistant epidemiologist) about the case(s) in the newborn ) phlegmonous and/or necrotic forms of omphalitis.

2.

Ultrasound examination of internal organs (if a phlegmonous or necrotic form of omphalitis is suspected).

3.

The following laboratory tests are prescribed:

-clinical blood test;

-blood culture to determine the sensitivity of microflora to antibiotics;

- culture of umbilical wound discharge to determine bacterial pathogens;

— determination of markers of the systemic inflammatory response (procalciotonin, C-reactive protein).

4. Additionally, for the phlegmonous form of omphalitis:

- consultation with a pediatric surgeon to confirm the diagnosis;

-requires hospitalization in the pediatric surgical department;

- surgical intervention is required;

— antibacterial therapy is prescribed taking into account sensitivity to drugs, immunoreplacement therapy with immunoglobulin preparations for intravenous infusions according to the instructions for the drug.

5. Additionally, for necrotic omphalitis:

- consultation with a pediatric surgeon to confirm the diagnosis;

-requires hospitalization in the pediatric surgical department;

- surgical intervention is required;

— antibacterial therapy is prescribed taking into account sensitivity to drugs, detoxification therapy, immunoreplacement therapy with immunoglobulin preparations for intravenous infusions according to the instructions for the drug.

6. Antibacterial therapy for phlegmonous and necrotizing omphalitis

Until the results of culture and microflora sensitivity are obtained, parenteral (intravenous or intramuscular) administration of drugs from the penicillin group in combination with aminoglycosides is recommended; the dose, method and frequency of administration are determined by the instructions for the drug.

If treatment is ineffective within 3 days

, the antibacterial therapy is changed to second generation cephalosporins (cefuroxime), the doses, method and frequency of administration are determined by the instructions for the drug.

When identifying methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

(MRSA) drugs from the group of glycopeptides (vancomycin) are prescribed; the dose, method and frequency of administration are determined by the instructions for the drug.

7. Local treatment.

- If there is only redness of the umbilical ring, without swelling and spreading of erythema to the skin around the umbilical ring, no treatment is required.

— In complicated forms of omphalitis (phlegmonous and necrotic), the scope of conservative therapy and indications for surgical intervention are determined by the surgeon.

III. Prevention (IA)1.

Compliance with the rules of asepsis and antisepsis when working with newborns.

2.

Compliance with the technique of crossing the umbilical cord, processing the umbilical cord residue in the delivery room, provided for by this protocol.

3.

Management of the umbilical remnant using the “dry method”.

4.

Ensuring that the hospital epidemiologist (assistant epidemiologist), deputy chief physician of the hospital, together with the heads of structural units, conducts active detection of nosocomial infections through prospective observation, which consists of the following:

-control of detection and prompt (daily) registration of purulent-inflammatory diseases;

-receiving daily information from all functional departments of the maternity hospital (department) about cases of infectious diseases among newborns and postpartum women, violations of the sanitary and epidemiological regime, and the results of bacteriological studies;

— investigation of the causes of their occurrence and information from management to take urgent measures.

5.

Accounting and registration of diseases of newborns caused by opportunistic microorganisms is carried out in accordance with ICD-10 codes.

6.

Introduction of infection control principles with regular audits of infectious inflammatory diseases in obstetric institutions and neonatology hospitals.

7.

Consulting the mother (parents) on the issues of caring for the skin of the newborn, the umbilical cord in conditions of joint stay and after discharge from the maternity hospital, with a note in the history of the child’s development.

Literature

1. Elhassani SB

The umbilical cord: care, anomalies, and diseases // South. Med. J. - 1984. - Vol. 77, N 6. - P. 730-736.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Neonatal tetanus - Montana, 1998 // MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. — 1998. Nov. 6. - Vol. 47, N 43. - P. 928-930.

3. The World Health Report 1998. Life in the 21st century. A vision for all. Geneva. World Health Organization; 1998, CHRPSR 1999 // Int. J. Epidemiol. - 1997. - Vol. 26, N 4. - P. 897-903.

4. Bennett J., Macia J., Traverso H. et al.

Protective effects of topical antimicrobials against neonatal tetanus. Source Task Force for Child Survival and Development. - Atlanta, Georgia, USA: Meegan, 2001.

5. Dore S., Buchan D., Coulas S.

Alcohol versus natural drying for newborn cord care // JOGNN. - 1998. - Vol. 27. - P. 621-627.

6. Zupan J., Garner P.

Topical umbilical cord care at birth (Cochrane Review) // The Cochrane Library. - 2001. - Is. 2. Oxford, Copyright © 2007 The Cochrane Collaboration. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd World Health Organization, Reproductive Health (Technical Support) Maternal and Newborn Health/Safe Motherhood, Geneva. Care of the Umbilical Cord, A review of the evidence 1999.

7. Hutton EK, Hassan ES

Late vs early clamping of the umbilical cord in full-term neonates. Systematic review and metaanalysis of controlled trials // JAMA. - 2007. - Vol. 297. - P. 1241 1252.

8. Shabalov N.P.

Neonatology: Textbook. manual: In 2 volumes, 5th ed., revised. and additional - M.: MEDpress-inform, 2009. - T. 1. - P. 184.

9. Basic assistance - international experience / Ed. N.N. Volodina, G.T. Dry; scientific ed. E.N. Baibarina, I.I. Ryumina. - M.: GEOTAR-Media, 2008. - 208 p. (Series “Library of a Medical Specialist”) 10. Cullen T.

Embryology, Anatomy, and Diseases of the Umbilicus Together with Diseases of the Urachus. — Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders, 1916.

11. Forshall 1957 Septic umbilical arteritis // Arch. Dis. Child. - 1957. - Vol. 32. - P. 25-30.

12. Kvasnaya L.G., Ostrovsky A.D.

Sepsis of newborns. - L.: Medicine, 1975.

13. National leadership / Ed. N.N. Volodina. - M.: GEOTAR-Media, 2007.

14. Shaffer TE, Baldwin JN, Rheins MS

Staphylococcal infections in newborn infants: I. Study of an epidemic among infants and nursing mothers // Pediatrics. - 1956. - Vol. 18. - P. 750-761.

15. Baldwin JN, Rheins MS, Sylvester RF

Staphylococcal infections in newborn infants: III. Colonization of newborn infants by staphylococcus pyogenes // Am. J. Dis. Child. - 1957. - Vol. 94. - P. 107-116.

16. Corner BD, Crowther ST, Eades SM

Control of staphylococcal infection in a maternity hospital: Clinical survey of the prophylactic use of hexachlorophane // Br. Med. J. - 1960. - Vol. 1. - P. 1927-1929.

17. Gillespie W.A., Simpson K., Tozer R.

Staphylococcal infection in a maternity hospital: Epidemiology and control // Lancet. - 1958. - Vol. II. - P. 1075-1084.

18. Gluck L., Simon HJ, Yaffe SJ

Effective control of staphylococci in nurses // Am. J. Dis. Child. - 1961. - Vol. 102. - P. 737-739.

19. Gluck L., Wood H.

Effect of an antiseptic skin-care regimen in reducing staphylococcal colonization in newborn infants // N. Engl. J. Med. - 1961. - Vol. 265. - P. 1177-1181.

20. Hardyment AF, Wilson RA, Cockcroft W.

Observations on the bacteriology and epidemiology of nursery infections // Pediatrics. - 1960. - Vol. 25. - P. 907-918.

21. Hurst V.

Transmission of hospital staphylococci among newborn infants: I. Observations on the contamination of a new nursery // Pediatrics. - 1960. - Vol. 25. - P. 11-20.

22. Jellard J.

Umbilical cord as reservoir of infection in a maternity hospital // Br. Med. J. - 1957. - Vol. 1. - P. 925-928.

23. Simon HJ, Yaffe SJ, Gluck L.

Effective control of staphylococci in a nursery // N. Engl. J. Med. - 1961. - Vol. 265. - P. 1171-1176.

24. Williams CPS, Oliver TK Nursery routines and staphylococcal colonization of the newborn // Pediatrics. - 1969. - Vol. 44. - P. 640-646.

25. Mendenhall AK, Eichenfield LF

Back to basics: Caring for the newborn's skin // Contemp. Pediatr. - 2000. - Vol. 17. - P. 98-114.

26. Czarlinsky DK, Hall RT,

Barnes WG Staphylococcal colonization in a newborn nursery, 1971-1976 // Am. J. Epidemiol. - 1979. - Vol. 109. - P. 218-225.

27. Pildes RS, Ramamurthy RS, Vidyasagar D.

Effect of triple dye on staphylococcal colonization in the newborn infant // J. Pediatr. - 1973. - Vol. 82. - P. 987-990.

28. Barrett FF, Mason EO, Fleming D.

Brief clinical and laboratory observations: The effect of three cord-care regimens on bacterial colonization of normal newborn infants // J. Pediatr. - 1979. - Vol. 94. - P. 796-800.

29. DeLoache WR, Cantrell HF, Reubish GK

Prophylactic treatment of umbilical stump: Comparison of techniques // South. Med. J. - 1976. - Vol. 69. - P. 627-628.

30. Perry D.S.

The umbilical cord: Transcultural care and customs // J Nurse Midwifery. - 1982. - Vol. 27. - P. 25-30.

31. Cloherty JP, Eichenwald EC, Stark AR

Manual of Neonatal Care. 6th ed. - Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2008. - P. 297-298.

32. Seidel

N.M. , Rosenstein B.J., Pathak A., McKay WH

the Newborn. 4th ed. - 2006. - P. 391-393.

33. Novack A.H., Mueller B., Ochs H.

Umbilical cord separation in the normal newborn // Am. J. Dis. Child. - 1988. - Vol. 142. - P. 220-223.

34. Medves JM, O

'

Brien BAC

Cleaning solutions and bacterial colonization in promoting healing and early separation of the umbilical cord in healthy newborns // Can. J. Public Health. - 1997. - Vol. 88. - P. 380-382.

35. Howard R.

The appropriate use of topical antimicrobials and antiseptics in children // Pediatr. Ann. - 2001. - Vol. 30. - P. 219-224.

36. Spray A., Siegfried E.

Dermatologic toxicology in children // Pediatr. Ann. - 2001. - Vol. 30. — P. 197-202

37. Paes B., Jones CC

An audit of the effect of two cord-care regimens on bacterial colonization in newborn infants // Qual. Rev. Bull. - 1987. - Vol. 13. - P. 109-113.

38. Gladstone I.M., Clapper L., Thorp J.W.

Randomized study of six umbilical cord care regimens: Comparing length of attachment, microbial control, and satisfaction // Clin. Pediatr. - 1988. - Vol. 27. - P. 127-129.

39. Verber IG, Pagan FS

What cord care: If any? //Arch. Dis. Child. - 1993. - Vol. 68. - P. 594-596.

40. Darmstadt GL, Dinulos JG

Neonatal skin care // Pediatr. Clin. North Am. - 2000. - Vol. 47. - P. 757-782.

41. Stark V., Harrisson SP

Staphylococcus aureus colonization of the newborn in a Darlington hospital // J. Hosp. Infect. - 1992. - Vol. 21. - P. 205-211.

42. Watkinson M., Dyas A.

Staphylococcus aureus still colonizes the untreated neonatal umbilicus // J. Hosp. Infect. - 1992. - Vol. 21. - P. 131-135.

43. Andrich MP, Golden SM

Umbilical cord care: A study of bacitracin ointment vs. triple dye // Clin. Pediatr. - 1984. - Vol. 23. - P. 342-344.

44. Taquino LT

Promoting wound healing in the neonatal setting: Process versus protocol // J. Perinat. Neonat. Nurs. - 2000. - Vol. 14. - P. 104-115.

45. McConnell TP, Lee CW, Couillard M. et al.

Trends in Umbilical Cord Care: Scientific Evidence for Practice NBIN. - 2004. - Vol. 4, N 4. - P. 211-222. ©2004 WB Saunders.

46. Mullany LC, Darmstadt GL, Khatry SK et al.

Topical applications of chlorhexidine to the umbilical cord for the prevention of omphalitis and neonatal mortality in southern Nepal: a community-based, cluster-randomised trial // Lancet. — 2006. Mar. 18. - Vol. 367, N 9514. - P. 910-918.

47. Capurro H.

Topical umbilical cord care at birth: RHL commentary (last revised: 30 September 2004). The WHO Reproductive Health Library. - Geneva: World Health Organization, 2004.

48. Sanitary and epidemiological rules and regulations. SanPiN 2.1.3.2630 - 10

49. Resolution of the Chief State Sanitary Doctor of the Russian Federation dated May 18, 2010 No. 58, IV, pp. 76-95.

Treatment of navel inflammation

At home, only catarrhal omphalitis and incomplete fistula are treated. Other diseases of the navel wound require complex treatment in a hospital setting (local treatment, antibacterial therapy and, if indicated, surgical treatment). With catarrhal form, newborns are shown hygienic baths with decoctions of string, chamomile, celandine, and potassium permanganate . Local treatment consists of treating the wound with hydrogen peroxide , potassium permanganate , brilliant green , chlorophyllipt propolis solution , and gentian violet .

You can use a combination drug - Baneocin (bacitracin + neomycin). Both components act bactericidal. This drug is safe and can be used from the first days of life. When using it, the umbilical wound is epithelized 2 times faster than with standard treatment (hydrogen peroxide + brilliant green or potassium permanganate). If erosions are present, they are completely epithelialized within 7 days when using Baneocin ointment. Premature babies are given two courses of antibiotics for 7 days each (an antibiotic is prescribed for the second course, taking into account the sensitivity of the microflora). For fungus, cauterization of granulations with a solution of silver nitrate - the procedure is performed by a doctor.

In case of phlegmonous form, in a hospital setting, bandages are made with Dimexide Levosin and Levomikol ointments . A 25% magnesium sulfate solution can be used as a hypertonic solution. In case of phlebitis and arteritis of the navel vessels, the wound is treated as a weeping navel and purulent omphalitis and bandages with Troxerutin .

Treatment of incomplete fistulas in newborns during the first months is carried out conservatively in the hope of a natural cure. Prescribe baths with a solution of potassium permanganate, treat the fistula tract with hydrogen peroxide and apply bandages with a 1% solution of chlorophyllipt . If these measures are ineffective, surgery is indicated. In case of necrotic form and gangrene after surgery, hydrophilic-based ointments ( Levomekol , Levosin ) are used on the wound.

Features of the treatment of inflammation of the umbilical zone

When treating omphalitis, the doctor takes into account its shape. If local disinfection procedures are sufficient to treat simple inflammation, then a course of antibiotics and even surgical intervention are required to eliminate the purulent or necrotic form. In a simple form, the following methods are used:

- treat the wound with hydrogen peroxide and apply an aqueous solution of antiseptics - 70% alcohol, chlorophyllipt, dioxynide or furatsilin;

- carry out procedures at least 3 times a day, always combining them with hygiene of the umbilical zone;

- hydrogen peroxide is applied with a sterile pipette, which is boiled for 30 minutes;

- After this, dry the surface and bottom of the navel with a cotton swab, then moisten a cotton swab with an antiseptic and blot the area.

Sometimes silver nitrate is prescribed to cauterize the umbilical zone (fungus).

Therapy of phlegmonous form

To eliminate this type of omphalitis, it is necessary to involve a surgeon. The wound is treated classically with antiseptics, and an antibacterial ointment is also placed in the umbilical fossa:

- Vishnevsky;

- Bacitracin;

- Polymyxin.

Antibiotics are prescribed by your doctor, but in some cases they are not required. Also, to strengthen the immune system, anti-staphylococcal immunoglobulin may be prescribed if tests reveal the pathogen.

Therapy of necrotic form

Be sure to surgically remove the affected tissue. They are cut off to healthy skin, then antibacterial and detoxification therapy is carried out, special solutions are injected inside and antiseptics are taken. After surgery, you can use healing agents: sea buckthorn or rosehip oil.

Physiotherapeutic procedures help recovery and can be used for any form of omphalitis: UHF and microwave therapy, laser treatment.

Prevention

Measures to prevent omphalitis in adults are:

- avoiding injuries to the umbilical area;

- maintaining personal hygiene and caring for the umbilical area, especially in case of obesity and excessive sweating ;

- performing piercings in beauty salons, which carefully monitor the disinfection of instruments;

- treatment with antiseptic compounds after piercing;

- rational nutrition to maintain a high level of immunity;

- If signs of inflammation appear, start antiseptic treatment and consult a doctor promptly.

Measures to prevent this disease in children include:

- Treatment of urogenital infections in pregnant women, as they cause omphalitis in the newborn.

- Compliance with the technique of cutting the umbilical cord and processing the remainder after childbirth.

- Compliance with the rules of asepsis and antisepsis in the delivery room and when working with newborns.

- Application of the “dry method” of managing the umbilical remnant. It is intended to keep the umbilical cord dry and clean. It should be left outdoors (or covered with a cloth) and allowed to dry naturally. In the area of the stump there is no need for regular application of antiseptic agents that irritate the skin and disrupt its integrity. The passage of the umbilical cord occurs faster if natural drying is used.

- Teaching mothers to care for the umbilical cord of a newborn. It is important to prevent its contamination, and it is also not advisable to apply antiseptic solutions unless necessary. Their application changes the microbiocenosis of the skin .

Forecast

For mild forms and inflammation of the umbilical vessels, the prognosis is favorable if treatment is carried out promptly and correctly. The simple (catarrhal) form responds well to treatment and most often does not lead to complications. However, given the long healing process even with catarrhal form, an infected wound poses a risk of developing a purulent-septic process. A variety of exogenous and endogenous causes can cause an outbreak of purulent inflammation.

Purulent-septic forms are initially severe and have dangerous complications, so the prognosis for them is always serious. The success of treatment of necrotic and purulent forms depends on the time of initiation of therapy. If treatment for some reason began late, the inflammatory process spreads to the anterior abdominal wall and becomes the cause of the development of abscesses and fistulas. In purulent-septic forms, there is a high mortality rate, since phlegmonous and necrotizing omphalitis is very often complicated by sepsis , which becomes the cause of death.