The pharmaceutical product is one of the most common medications and has a wide range of therapeutic effects. In tablet form, it is often prescribed to patients of all age groups.

Many people wonder how to be treated with Ibuprofen, what are their benefits, but even if you know the answers to these questions, do not rush to start using them without consulting a doctor

When is it appointed?

Ibuprofen is to some extent a harmless drug, but if there are contraindications noted in the instructions, you should stop using the medicine. The opposite can lead to dire consequences. In addition, you cannot take an increased dose of medication, as there is a serious danger to life and health.

Benefits for headaches

Ibuprofen will be a good help when you suffer from excruciating headaches. In particular, it is prescribed for migraines, characterized by prolonged pain. In this situation, the drug should be used as soon as possible after the onset of migraine symptoms. If your health does not improve, repeat taking the medicine after 5 hours. This treatment regimen is very effective and most often leads to a positive result.

When nervous tension occurs, “discomfort” occurs; in this situation, an Ibuprofen tablet will help.

Ibuprofen for toothache and menstruation

The medicine is a pathognomonic drug. If there is no way to get an appointment with a dentist, you can take an Ibuprofen tablet to relieve toothache. You should not take more than 6 tablets of the drug per day, the treatment course is a maximum of 5 days.

Ibuprofen will be useful after implant placement and tooth extraction; it will help relieve pain.

During menstruation, many women experience pain; to relieve it, it is advisable to take Ibuprofen. However, you should beware of overdose. The first dosage should be 400 mg; if the discomfort does not go away, after a few hours you will have to repeat the medication.

Treatment in this case should not exceed 3 days; if a positive result is not noted, consult a doctor.

Ibuprofen for colds

Each property of the drug is very effective for various types of colds. After taking Ibuprofen, the fever quickly passes, pain decreases, due to which the patient’s condition quickly returns to normal.

To treat colds, tablets can be prescribed to persons over 12 years of age. The doctor may prescribe a different dosage than indicated in the instructions. Of course, Ibuprofen alone is not enough to get rid of a cold, but its anti-inflammatory properties help enhance the effects of other medications. Thanks to all this, recovery is accelerated.

Ibuprofen for fever

With many illnesses, people's body temperature rises; Ibuprofen will help reduce it. The pharmaceutical is prescribed as part of a complex therapeutic course for various diseases:

- Cold

- Injuries

- ENT diseases

- Viral, bacterial infections

- Joint and muscle pain

On what could such statements be based?

In May 2022, the EMA Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) published a review of ibuprofen and ketoprofen following a survey by the French Agency for the Safety of Medicines and Health Products (ANSM), which indicated that the course of chickenpox and some other bacterial infections may be worsened by these medications. However, the instructions for medical use of NSAIDs already contain warnings that the anti-inflammatory effects of these drugs may hide the symptoms of exacerbation of infection.

The Lancet, one of the oldest and most respected medical journals, published a letter on March 11, 2022, which suggested that some anti-inflammatory drugs, such as ibuprofen, may increase the risk of complications of coronavirus infection by stimulating the rise of ACE-2. This letter caused a lively discussion, as it was not supported by any facts. Further research completely refuted it. This letter has now been withdrawn from the journal.

A little later, the European Medicines Agency EMA expressed its position. “ There is currently no scientific evidence linking ibuprofen to worsening health in patients with COVID-19. The EMA is closely monitoring the situation and will consider any new information that becomes available on this issue in the context of the pandemic. When initiating treatment for patients with COVID-19, healthcare providers should consider all available treatment options, including paracetamol and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, to reduce fever and pain. In accordance with EU national treatment guidelines, patients and healthcare professionals can continue to use non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (such as ibuprofen) as prescribed. There is currently no reason for patients taking ibuprofen to interrupt their treatment based on the above. This is especially important for patients taking ibuprofen or other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to treat chronic conditions."

On March 19, 2022, the WHO stated a sudden change of position: " WHO is consulting with physicians treating patients with COVID-19 and is not aware of any reports of any negative effects of ibuprofen , other than the usual known side effects that limit it use in certain populations."

The Commission on Human Medicines Coronavirus (COVID-19) Expert Working Group concluded on 14 April 2022 that there is currently insufficient evidence to establish an association between the use of ibuprofen or other NSAIDs and worsening coronavirus infection . “Patients can take paracetamol or ibuprofen to self-treat COVID-19 symptoms such as fever and headache.”

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) also said it has no scientific evidence linking the use of NSAIDs such as ibuprofen to worsening COVID-19 symptoms.

Use during pregnancy and breastfeeding

It is not advisable to take ibuprofen and certain medications while pregnant. Although fever and pain pose a threat, the corresponding signs require quick elimination.

Ibuprofen, as recommended by your doctor, can be taken in the 2nd trimester; you should not be treated with it if there are contraindications. The medicine is contraindicated in the first or third trimester of pregnancy.

When breastfeeding, the medicine also quickly eliminates fever and eliminates pain. However, it can pass into breast milk and cause some harm to the baby, although there will be no serious health hazard. If there is an urgent need to take medication, the tablet should be taken after feeding. The concentration of the active substance in milk reaches a large amount 2 hours after administration, and then begins to rapidly decrease.

Safety of ibuprofen in clinical practice

B

ol is the body’s main reaction to any tissue damage, so its relief is a problem for doctors of any specialty.

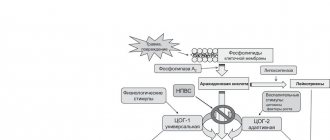

According to modern ideas about the mechanisms of development and transmission of the pain signal, a comprehensive approach using various groups of pharmacological agents is considered a reasonable treatment for pain, the mechanism of action of which is primarily aimed at suppressing the synthesis of inflammatory mediators and limiting the flow of nociceptive information from the periphery to the central nervous system.

Analgesics are widely used throughout the world. In England, more than 20 million people receive prescriptions for non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and in one year (1999–2000) more than 100 million prescriptions were written for COX-2 inhibitors [18].

NSAIDs are most in demand primarily in rheumatic diseases for the relief of articular syndrome, in trauma, postoperative conditions, renal colic, migraine, dysmenorrhea, neurological diseases, and recently their preventive effect in colon cancer and Alzheimer's disease has been discussed. According to a survey conducted in Western European countries, NSAIDs are prescribed by more than 80% of general practitioners

[5,18].

The leading place in sales is occupied by over-the-counter analgesics, which are used as antipyretics and pain relievers of various origins: headaches, dental pain, dysmenorrhea, etc.

In 1998, 16.1 billion over-the-counter NSAIDs were sold in the United States, compared with 2.9 billion prescription ones. Of particular concern is the violation of the drug dosage regimen (about 1/3 of patients take prescription NSAIDs in larger doses than recommended by the doctor).

Given the predicted “aging” of the planet, the number of people needing to take NSAIDs will steadily increase. This poses a challenge for physicians to ensure the safety of NSAID treatment. In the United States, more people die each year from medical errors than from street injuries, lung cancer, and AIDS [22]. One of the reasons for this is ignorance of the mechanism of action of drugs, especially when used in combination, and possible adverse reactions.

Currently, the issue of safety of NSAIDs comes first. Possible side effects when using NSAIDs include damage to the gastrointestinal tract, impaired platelet aggregation, renal function, and a negative effect on the cardiovascular system. Gastrointestinal disorders are the most common side effects with NSAID use. Among the frequently used NSAIDs, we can highlight drugs that are particularly unfavorable in this regard - indomethacin, piroxicam, flurbiprofen; relatively safe drugs are ibuprofen, diclofenac, ketoprofen, as well as selective COX-2 inhibitors [4,9].

A number of researchers explain the clinical effect and the development of adverse reactions by the half-life of NSAIDs, with the more dangerous of them being long-lived ones (Table 1).

The development of side effects is often dose-dependent, as shown in Table 2, from which it follows that the analgesic dose of ibuprofen (1200 mg/day) is as safe as placebo. The main mechanism determining the safety of the drug is its ability to suppress the activity of cyclooxygenase-2 (Table 3). However, a direct relationship between the anti-inflammatory and analgesic effect and the severity of COX-2 inhibition was not identified. The most common side effects caused by inhibition of COX-1 and 5-lipoxygenase [19] are gastrointestinal damage, renal dysfunction, platelet aggregation, etc. (Table 4). It is believed that gastrointestinal side effects are one of the most common adverse events when using NSAIDs [27]. However, there was a clear dose dependence of the risk of developing NSAID gastropathy [14,16] (Table 5). A dose of ibuprofen 1200 mg/day is regarded as one of the safest in relation to gastrointestinal complications.

OTC NSAIDs are especially often used not only as analgesics, but also as antipyretics, competing with acetaminophen. A comparison of the effect of 400 mg of ibuprofen and 1000 mg of acetaminophen in the treatment of 113 patients with sore throat caused by tonsillitis-pharyngitis [10] showed that ibuprofen was significantly more effective, especially during the first 6 hours. With short-term use of these drugs, tolerability was equal.

A randomized trial of 3 analgesics: acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), acetaminophen, and ibuprofen was conducted in France and England with the participation of 1108 general practitioners. The study included 8677 adult patients with pain of musculoskeletal origin, throat, and acute respiratory infections [23]. Treatment was carried out for 1–7 days in doses: ASA and acetaminophen 3 g/day, ibuprofen up to 1.2 g/day. The frequency of significant adverse events when taking ASA was 18.7%, ibuprofen – 13.7%, acetaminophen – 14.5%. The total number of gastrointestinal complications was noted in 5.8% of those treated with ibuprofen, 7.3% with acetaminophen, and 10.6% with ASA. Gastrointestinal bleeding was absent in patients receiving ibuprofen, but was diagnosed in 4 patients on acetaminophen (which does not inhibit COX-1) and in 2 patients on ASA.

In terms of the time of development of gastrointestinal complications, treatment with ASA was the most unfavorable, because they appeared already on the first day after taking 1-2 tablets. Commission conclusion: General practitioners should give preference to ibuprofen over ASA and acetaminophen

due to the poorer tolerability of ASA and the potential for acetaminophen overdose.

The high safety of ibuprofen is also evidenced by the fact that it has been an over-the-counter drug for more than 20 years in the country where it was created in 1962 by S. Adams et al., who worked at Boots (UK) (Fig. 1) .

Rice. 1. Risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding associated with NSAID use [17]

Undesirable complications include complications from the cardiovascular system, in particular, heart failure, the risk of which is higher in patients with arterial hypertension, heart and kidney diseases (Table 6) [24]. According to the ANA, the frequency of these events when using NSAIDs in patients with hypertension exceeds 25%. The likelihood of developing heart failure is higher when using NSAIDs with a long half-life (piroxicam) than with a short half-life (ibuprofen, diclofenac). The risk of developing heart failure is higher in people over 55 years of age, especially in those taking diuretics. A randomized study of 8059 patients with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis receiving celecoxib 400 mg/day, ibuprofen 800 mg/day, diclofenac 75 mg/day. showed an equal frequency of cardiovascular complications [1].

A study of the effect of NSAIDs on blood pressure in 1213 hypertensive patients showed that when taking ibuprofen, mean blood pressure decreased by 0.3 mmHg. and increases by 6.1 mm Hg. when taking naproxen [25].

Neither classical NSAIDs nor selective COX-2 inhibitors provide cardioprotection, with the exception of low-dose ASA, which irreversibly inhibits COX-1 activity in platelets. The work [13] showed that taking ibuprofen before ASA can block the inhibition of platelet COX-1 and reduce platelet aggregation caused by ASA, without affecting the level of serum thromboxane B2. This fact should be taken into account when treating patients receiving ASA for the prevention of vascular complications, and its use should be recommended before ibuprofen, because this sequence does not cancel the effect of acetylsalicylic acid.

With the advent of a new class of NSAIDs—selective COX-2 inhibitors—the issue of their analgesic effectiveness compared to classical NSAIDs is being actively discussed [21]. The authors of this review indicate that in the literature, clinical studies of the effectiveness of selective COX-2 inhibitors in the treatment of non-arthritic diseases either give ambiguous results or are absent. Analgesia for postoperative dental pain with rofecoxib at a dose of 50 mg was equal to 400 mg of ibuprofen, and 200 mg of celecoxib was weaker. With regard to acute tonic pain, there is no evidence of equality between these two groups of NSAIDs. The authors believe that to achieve the maximum analgesic effect, inhibition of both COX isoforms is necessary, because There is evidence of a temporal and dynamic relationship between COX-1 and COX-2 and their participation in the formation of Pg E2 and subsequent clinical manifestations of pain [23].

The relative risk of developing edema in clinical practice among hypertensive patients in the United States is presented in Figure 2 [28]. As we see, ibuprofen has a clear advantage over the compared drugs.

Rice. 2. Relative risk of developing edema in clinical practice [31]

The

CLASS

[14], which compared the effect and tolerability of celecoxib and ibuprofen, showed that ibuprofen is inferior to celecoxib in the incidence of edema and increased blood pressure, but is safer than rofecoxib (Fig. 3).

Rice. 3. Hypertension and edema [14]

In rheumatology, NSAIDs are prescribed for almost all diseases, given their triple mechanism of action. In the foreign literature, the algorithm for the treatment of osteoarthritis is widely discussed, in which acetaminophen is placed in first place. A double-blind randomized study conducted [11] showed that in patients with gonarthrosis, the anti-inflammatory dose of ibuprofen was 2.4 g/day. was more effective than analgesic – 1.2 g/day. and 4.0 g/day. acetaminophen, which was confirmed by a decrease in joint pain and improvement in motor function.

An analysis of Medline data on the effect of various analgesics (meloxicam, naproxen, diclofenac, ibuprofen, celecoxib, rofecoxib, codeine, morphine [8]) on the severity of pain in osteoarthritis (OA) showed that the best clinical effect was achieved with the use of ibuprofen, diclofenac and naproxen.

A review [12] on the treatment of OA presents the results of a double-blind study of ibuprofen and benoxyprofen in a 4-week study, indicating a reduction in pain by 21% in both groups. Similar results were obtained when comparing fenoprofen calcium and ibuprofen.

Data [15,26] indicate equal effectiveness for gonarthrosis of ibuprofen at a dose of 1.2–2.4 g/day. and tramadol 200–400 mg/day, which once again confirms the high analgesic effect of ibuprofen.

A common reason for visiting a doctor and an equally common disability is low back pain (LBP), in which the acute phase of pain is usually limited to 7–8 days. NSAIDs are the drugs of choice for the management of this pain [6]. A comparative randomized study in which 48.3% of patients suffered from LBP showed that 1200 mg/day. ibuprofen is equivalent to 3 g of acetaminophen, more effective than 3 g of ASA and safer than ASA and acetaminophen [6].

The analgesic effect of 1200 mg ibuprofen for LBP was confirmed in one study [2], where it was shown that the average pain intensity according to VAS decreased by more than half on the second day, and by the sixth day it completely or significantly decreased in 73% of patients.

In the United States, up to 30% of visits to the doctor are related to fever in children [7]. Ibuprofen is allowed to be used as an antipyretic at a dose of 5–20 mg/kg, which is comparable to the effect of acetaminophen.

Issues of the effectiveness and safety of ibuprofen in pediatric practice are covered in the review of Prof. Geppe HA [3]. Pediatricians consider ibuprofen to be the best-tolerated NSAID in children

. Prof. Antret-Leca [3] concluded: “Compared with acetaminophen and ASA, ibuprofen has less toxicity in overdose and therefore a wider therapeutic range.”

The safety of ibuprofen is evidenced by the fact that it is approved for the treatment of children under 2 years of age. An analysis of treatment (double-blind study) of 84,000 children under 2 years of age for febrile illness with ibuprofen at a dose of 5–10 mg/kg and acetaminophen 12 mg/kg showed that ibuprofen did not increase the risk of hospitalization in children [20].

The presented data indicate that ibuprofen has a high analgesic effect at a dose of up to 1200 mg/day, is well tolerated by adults and children, is used in infants and premature infants, and is not inferior in tolerance to selective COX-2 inhibitors.

Literature:

1. Belousov Yu.B., Gurevich K.G. The effect of NSAIDs and paracetamol on the cardiovascular system. Wedge. pharmacological therapy, 2002, 5, 5–7

2. Vein A.M., Danilov A.B. The effectiveness of solpofex in the treatment of low back pain. Wedge. Pharmacol. Therapy, 1999, 8, 2, 47–78

3. Geppe NA First international conference on the use of ibuprofen in pediatric breast cancer, 2002, t10, no. 18, 831–835

4. Nasonov E.L. NSAIDs for rheumatic diseases: standard of treatment. RMZh, 2001, t9, no. 7–8, 265–270

5. Nasonov E.L. Use of NSAIDs: therapeutic aspects. RMJ, 2002, t10, no. 4, 206–212

6. Nasonova V.A. NSAIDs for acute pain in the lower back. Consilium medicum, 2002, v4, no. 2, 102–106

7. Tabolin V.A., Osmanov I.M., Dlin V.V. The use of antipyretics in childhood. Wedge. pharmak. therapy, 2002, t11, no. 5, 12–14

8. Babul N., Peloso PM Comparative Pharmacologic Response of analgesic agents on key outcome variables in osteoarthritis. X World Congress on Pain, USA, 2002 P 211

9. Biarnason IT The effects on NSAIDs on the small intestine: clinical implications. New Standards in Arthritis Care, 1997, v6, N 2, p2

10. Bourean F., Pelen F., ea Evaluation of Ibuprofen is Paracetamol Analgesic Activity using a Sore Throat Pain Model. Clin. Drug Invest., 1999, 17(1), 1–8

11. Brodley ID, Brandt KD, Kats BP ea Comparison of anti–inflammatory dose of ibuprofen, an analgesic dose of ibuprofen and acetomenofen in the treatment of patients with osteoarthritis. N.Eugl. J. med., 1991, 325, 87–91

12. Brandt KD The role of Analgesics in the Management of OA Pain Amer. J. Therapeutics, 2000, v7 N2, 75–90

13. Catella–Lawson F. E a Cyclooxygenase inhibitors and the Antiplatelet effects of Aspirin. The New Eugr. J.Med., 2001, v345, 25, 1809–17

14. CLASS Advisory Committee Briefing Document FDA Arthritis Advisory Committee Meeting 2001, Maryland, Gaithersburg

15. Dalgin P. Comparison of tramadol HCL and ibuprofen for the chronic pain of OA. Arthr. Rheum., 1997, 40, 586

16. Gabriel SE, Iaakkimainen L. ea Risk for serious gasthrointestinal complications related to use of NSAID. A meta-analysis. Am. Yntern. Med., 1991, 115: 787–796

17. Guthann S., Rodrigues G., Raiford FS Individual NSAIDs and other risk factors for Upper gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation. Epidemiology, 1997, 8, 18–24

18. Hillis WS Areas of Emerging interest in analgesics: cardiovascular complications. Am. J. Therapeutics, 2002, 9, 259–69

19. Laufer S., Tries S. Pharmacological profile of a new pyrrolizine derivative inhibiting the Enzymes COX and 5-lipoxygenase. Arzneim-Forsch Drug Res., 1994, 44: 629–636

20. Lesco SM The safety of acetaminophen and ibuprofen children less than two years old/ Pediatrics, 1999, 104, 4, 1–5

21. McCormack K., Twycross R. Are COX–2 selective inhibitors effective analgesics? Pain Reviews, 2001, 8, 13–26

22. Medical errors in the USA WHO pharmaceuticals Newsletter, 2000, N2, 13–14

23. Moore N. ea The pain study: paracetamol, aspirin, ibuprofen: New tolerance. Clinical Drug Invest., 1999, 18(2), 89–98

24. Page J., Henry D. Development of congestive heart failure in elderly patients: an under recognized public health problem. Arch. Int. Med., 2000, 160, 777–84

25. Pope JE, Anderson II, Felson DTA meta–analysis of the effects of NSAIDs on blood pressure. Arch. Int. Med., 1993, 153, 477–84

26. Reid E. Tramadol in Musculoskeletal Pain—a Survey. Clin. Rheumat., 2002, v21(suppl. 1), 9–12

27. Singh G. Gastrointestinal complications of prescription and over the counter NSAID; A view from the ARAMIS Database. Am. J. of Therapeutics, 2000, 7, 115–121

28. Zhao S. ea Comparison of edema clines associated with rofecoxib, celecoxib, and traditional NSAIDs among stable hypertensive patients in the US insured population. Am. Rheum. Dis., 2002, v 61, suppl 1, p 346