prepared by the author of the site based on materials

Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope (version 2009)

The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Syncope

of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)

Syncope (syncope, fainting) is an episode of temporary loss of consciousness due to general hypoperfusion of the brain. Syncope is characterized by an acute onset and rapid self-regression of symptoms.

The term “collapse” means a sharp decrease in blood pressure, but loss of consciousness is not necessary. In some cases, collapse can be the cause of fainting.

The ICD-10 category for both conditions is R55 Syncope and collapse.

ICD-10 identifies the following types of fainting conditions (“Emergency Therapy”, 2004, No. 1-2 (16-17), A.L. Vertkin, O.B. Talibov):

- psychogenic syncope (F48.8);

- sinocarotid syndrome (G90.0);

- heat syncope (T67.1);

- orthostatic hypotension (I95.1), incl. neurogenic (G90.3) and

- Stokes-Adams attack (I45.9).

The clinical picture of certain types of syncope includes a prodromal period with various symptoms: dizziness, general weakness, dizziness and visual disturbances, indicating the subsequent development of syncope. However, syncope often develops without warning.

Typically, syncope is short-lived, in 90% of cases the duration is 5-22 s. However, in some cases, attacks last longer - up to several minutes.

- Up to 90% of cases of syncope lasting more than half a minute are accompanied by clonic

- convulsions.

- The functions of the pelvic organs are usually monitored

- Pulse is weak,

- Blood pressure is reduced,

- Breathing is almost imperceptible.

(Algorithm for the diagnosis and treatment of syncope at the prehospital stage. Scientific and educational material. Moscow 2011)

After the end of syncope, a rapid and complete restoration of consciousness, orientation and adequate behavior is characteristic. Retrograde amnesia is rare and occurs mainly in older people. Some patients feel general weakness after an attack.

The adjective "presyncope" is used to describe the symptoms and signs that precede the loss of consciousness of syncope, being the prodrome of syncope. Thus, “presyncope” or “lipothymia” refers to the prodromal state of syncope without the subsequent development of loss of consciousness.

For the development of cerebral hypoperfusion, a decrease in systolic blood pressure below 60 mm Hg is sufficient. lasting 6-8 seconds. In addition, syncope can be caused by a rapid decrease in blood oxygenation.

Reflex (neurogenic) syncope

Vasovagal (neurocardiogenic) syncope

- mediated by emotional stress: fear, pain, the sight of blood;

- mediated by orthostatic stress

Situational syncope

- cough;

- sneezing;

- defecation;

- urination;

- swallowing (cold liquid);

- postprandial (after eating);

- manipulations in the hairdressing salon;

- playing the trumpet;

- strangulation;

- lifting weights;

- diving under water;

- stretching exercises.

Carotid sinus hypersensitivity

Atypical syncope (with/without obvious trigger)

Syncope due to orthostatic hypotension

Primary autonomic failure

- primary autonomic failure,

- multiple system atrophy,

- Parkinson's disease with autonomic failure,

- dementia with Lewy bodies

Secondary autonomic failure

- diabetes mellitus, amyloidosis, uremia, spinal cord lesions;

- drug-induced orthostatic hypotension;

- alcohol, vasodilators, diuretics, phenothiazines, antidepressants.

Hypovolemia

- bleeding, diarrhea, vomiting, etc.

Cardiogenic syncope

Arrhythmogenic

Bradycardia

- complete AV block (III degree AV block);

- Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome;

- sick sinus syndrome.

Tachycardia

- supraventricular;

- ventricular

Long QT syndrome

Channelopathies

Structural heart lesions

- aortic stenosis;

- dissection and aortic aneurysm;

- acute myocardial infarction/myocardial ischemia;

- hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy;

- pathology of the coronary arteries;

- primary pulmonary hypertension;

- pulmonary embolism;

- Eisenmenger syndrome;

- heart valve diseases;

- atrial myxoma;

- arrhythmogenic dysplasia of the right ventricle.

Conditions with partial or complete loss of consciousness, but without global cerebral hypoperfusion

- epilepsy;

- metabolic disorders (hypoglycemia, hypoxia, hyperventilation);

- intoxication;

- TIA in the vertebrobasilar region.

Conditions without loss of consciousness

- functional (psychogenic) syncope;

- drop attacks;

- transient ischemic attacks in the carotid region;

- cataplexy;

- paroxysmal dyskinesias;

- paroxysmal kinesiogenic choreoathetosis;

- paroxysmal non-kinesiogenic choreoathetosis;

- paroxysmal dyskinesias caused by physical activity;

- periodic syndromes of childhood;

- benign paroxysmal vertigo;

- benign paroxysmal torticollis;

- cyclical vomiting.

Other paroxysmal nonepileptic disorders

- levodopa-sensitive dystonia;

- episodic ataxia;

- Sandifer syndrome;

- nodule spasm;

- paroxysmal tonic upward abduction of the eyes in children;

- Benign nonepileptic myoclonus of infancy;

- congenital hyperekplexia;

- Seizures of shuddering;

- stereotypies, self-irritation and masturbation;

- Hyperventilation syndrome.

Syncope is an emergency and requires immediate patient evaluation. In the absence of indications of known medical conditions or medications taken by the patient, the clinical characteristics of the attack provide basic information about the nature of syncope.

Sources of development

In a healthy person, from 60 to 100 ml of blood moves through the cerebral arteries for every 100 g of GM substance every minute. A sharp drop in the reading to a level of up to 20 mg leads to short-term fainting. The list of factors influencing the occurrence of syncope is presented:

- decreased cardiac output (severe arrhythmia, heart attack, acute massive blood loss, ventricular tachycardia, slow heartbeat, hypovolemia arising from diarrhea of profuse etiology);

- decrease in the volume of the lumen of the cerebral arteries (atherosclerosis, spasm of blood vessels, occlusion of the carotid artery);

- dilatation of blood vessels;

- orthostatic collapse due to a sudden change in body position.

Neuroreflex changes in vascular tone are considered the main primary source of the formation of fainting. For their appearance, the following factors must be present:

- unstable psycho-emotional status;

- pain syndrome;

- irritation during swallowing, coughing or sneezing of the CS and the 10th pair of cranial nerves (Roemheld syndrome, examination of the eardrums);

- renal colic, exacerbation of inflammation of the gallbladder;

- neuralgia: trigeminal or glossopharyngeal nerve;

- VSD, excess of medication norms.

The second mechanism that causes syncoma is a drop in oxygen content in the blood. Fainting of this type occurs against the background of:

- blood pathologies - iron deficiency or sickle cell anemic condition;

- respiratory lesions, concentrated carbon monoxide poisoning.

A decrease in CO2 contained in the bloodstream during intense breathing also provokes fainting. About 41% of the causes of syncoma cannot be recognized.

History taking

Character of attacks

In order to determine whether an attack was syncope or another type of paroxysmal state, it is necessary to answer the following questions:

- Was the loss of consciousness complete?

- Was the loss of consciousness transient: short-term with rapid recovery?

- Has the patient recovered completely, spontaneously, and without sequelae?

- Was there a decrease in the tone of the muscles supporting the posture?

If the answer to each question is “yes,” the patient is likely experiencing syncope; if the answer is “no” to at least one of the questions, it is necessary to consider other causes of paroxysm.

Number of episodes

As a rule, benign causes are characterized by a small number of syncope and their rare development. In contrast, dangerous causes of syncope cause frequent syncope.

Associated symptoms

Dyspnea may indicate a connection between syncope and pulmonary embolism;

Angina pectoris - for heart disease; The sudden development of syncope (without a prodrome) is also characteristic of cardiogenic syncope, however, due to the fact that reflex syncope is more common, there are more cases of reflex syncope with a sudden onset than cardiogenic ones.

Focal neurological symptoms are associated with neurogenic syncope.

Blood in stool and vomit, melena are signs of gastrointestinal bleeding.

Involuntary urination and defecation , prolonged course - the epileptic (not syncope) nature of the attack.

However, none of the clinical signs is pathognomonistic; a clinical indication of a certain type of syncope does not exclude the need for a complete examination of the patient.

A more detailed overview of possible causes is given in the table below:

Table 1 diagnostic signs of various types of syncope

| Recommendations | Class | Level |

| VVS is diagnosed when syncope is provoked by emotional stress or orthostatic load and is combined with a typical prodrome. | I | C |

| Situational syncope is diagnosed if it occurs during or immediately after the action of special triggers (triggers) | I | C |

| Orthostatic syncope is diagnosed if it occurs after moving to an upright position and/or the patient has had orthostatic hypotension. | I | C |

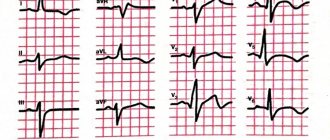

| Arrhythmogenic syncope is diagnosed if the following changes are detected on the ECG: | I | C |

| - persistent sinus bradycardia <40 beats/min while awake or repeated episodes of sinoatrial block, or sinus pauses ≥3 s; - atrioventricular block 2nd degree (Mobitz II) or 3rd degree; - alternating blockade of the right or left bundle branches; - ventricular tachycardia or paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia; - unstable episodes of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia and long or short QT interval syndrome; - malfunction of a pacemaker or artificial pacemaker | ||

| Syncope due to myocardial ischemia is diagnosed if the patient has ECG evidence of acute ischemia, with or without evidence of infarction. | I | C |

| Syncope caused by structural heart disease is diagnosed in the case of atrial myxoma causing valve dysfunction, severe aortic stenosis, pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary embolism, or acute aortic dissection. | I | C |

European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), Heart Failure Association (HFA), Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), et al.

Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope (version 2009): the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Syncope of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC).

Eur Heart J 2009; 30:2631.

Clinical characteristics that indicate the type of syncope at initial evaluation

Neurogenic syncope:

- no signs of heart disease;

- long-term course of recurrent syncope;

- development after an attack of pain, a sudden unpleasant sight, sound or smell;

- standing for long periods of time or being in a crowd or in hot rooms;

- a combination of nausea and vomiting with syncope;

- during or after meals;

- connection with head turns or pressure on the carotid sinus area (neck tumors, shaving, tight collar);

- development after load.

Syncope due to orthostatic hypotension:

- after moving to a vertical position;

- temporary association with the initiation or change in dose of vasodilator drugs that cause hypotension;

- standing for long periods of time, especially in a crowd or in hot rooms;

- presence of autonomic polyneuropathy or parkinsonism

- getting up after physical activity.

Cardiogenic syncope:

- established structural abnormalities of the heart;

- history of unexplained sudden death or channelopathy;

- during exercise or in a lying position;

- sudden palpitations just before syncope develops;

- ECG changes indicating arrhythmogenic syncope:

- Bifascicular block (defined as either a left or right bundle branch block combined with a left anterior or left posterior bundle branch block)

— Other intraventricular conduction disorders (QRS interval duration ≥0.12 s)

— 2nd degree AV block, Mobitz I

— Asymptomatic sinus bradycardia (<50 beats/min), sinoatrial block or sinus pauses ≥3 s without taking drugs with a negative chronotropic effect

— Unsustained ventricular tachycardia

— Premature ventricular complexes (QRS complexes)

— Long or shortened QT interval

— Early repolarization

— Signs of right bundle branch block with ST elevation in leads V1-V3 (Brugada syndrome)

- Negative T waves in the right precordial leads, ε waves and late ventricular potentials indicating arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy

- Q waves indicating myocardial infarction

Syncope (from the Greek syncope - break, pause) is a sudden short-term transient loss of consciousness (LTC), resulting from general hypoperfusion of the brain, accompanied by loss of postural tone, often leading to a fall.

The term "syncope" roughly corresponds to the term "syncope", but is applicable primarily to vasovagal syncope. There are traumatic (due to TBI) and non-traumatic TPS. The relevance of this topic is growing and is interdisciplinary in nature, while there are not so many scientific studies and publications on syncope.

Interdisciplinary nature of syncope

During life, syncope (SS) occurs at least once in 35–50% of people. There are two peaks for the development of SS: at the age of 10–35 years and after 65 years. SS account for 1–3% of all emergency room visits and approximately 6% of all PICU admissions. In the general population, reflex fainting clearly dominates - up to 2/3 of all SS. A high probability of recurrence of vasovagal syncope has been established, varying in the range of 25–35% of cases per year.

CVs are a risk factor for sudden cardiac death and traumatic injuries for both the patient and others (syncope in drivers, people working in harmful and dangerous working conditions, etc.). The main threat is not loss of consciousness as such, but the underlying mechanisms of fatal disturbances in heart rhythm and conduction, which directly relates to emergency cardiology, functional diagnostics and invasive arrhythmology.

Currently, syncope is generally considered from the perspective set out in the new clinical Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of syncope, published in 2022 by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). The latest edition focuses on improving the effectiveness of diagnostic and treatment measures, as well as assessing prognosis, reducing the risk of relapse and life-threatening consequences of CVD. It is proposed to consider syncope not only as a cardiac problem, but also as a phenomenon that doctors of different specialties have to deal with. It is also recommended to base diagnostic decisions on the results of long-term observation of the patient.

A new approach is the created electronic version of practical instructions, algorithms for diagnosing and treating TPS, available on the EOC website (www.escardio.org). The Ministry of Health of Belarus approved the Instruction on the procedure for providing specialized medical care to patients suffering from paroxysmal conditions (Order of the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Belarus dated February 27, 2014 No. 189), and published an educational manual “Syncopal conditions in the practice of a therapist” (Minsk, BSMU, 2013).

Classification of syncope

Reflex syncope

- Vasovagal:

- orthostatic VVS: in a standing position, less often in a sitting position;

- emotional stress: fear, pain (somatic or visceral), performing instrumental interventions, fear of blood.

- Situational:

- urination;

— stimulation of the gastrointestinal tract (swallowing, defecation);

- cough, sneezing;

- post-load;

- others (for example, laughter, playing wind instruments).

- Carotid sinus syndrome.

- Non-classical forms: without prodrome, and/or without obvious triggers, and/or atypical manifestations.

Syncope due to orthostatic hypotension (OH)

It must be remembered that hypotension can increase with fluid retention in the venous system during physical activity (stress), after eating (postprandial) and after a long stay in a lying position (detraining).

- Drug-induced OH (most common cause):

- when taking vasodilators, diuretics, phenothiazines, antidepressants.

- Decrease in circulating blood volume:

- bleeding, diarrhea, vomiting, etc.

- Primary autonomic dysfunction (neurogenic OH):

- idiopathic autonomic dysfunction, multiple system atrophy, Parkinson's disease, dementia with Lewy bodies.

- Secondary autonomic dysfunction (neurogenic OH):

- diabetes mellitus, amyloidosis, spinal cord damage, autoimmune autonomic neuropathy, paraneoplastic autonomic neuropathy, renal failure.

Cardiac syncope

Rhythm disturbances as the primary cause:

- bradycardia:

— sinus node dysfunction (including tachy-brady syndrome),

- violation of atrioventricular conduction;

- tachyarrhythmias:

- supraventricular,

- ventricular.

Structural heart disease: aortic stenosis, acute myocardial infarction/ischemia, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, intracardiac neoplasms (myxoma cardiac, other tumors), pericardial disease/cardiac tamponade, congenital anomalies of the coronary arteries, prosthetic heart valve dysfunction.

Cardiopulmonary pathology and vascular pathology: thromboembolism of the pulmonary artery and its branches, acute aortic dissection, pulmonary hypertension.

Diagnosis of syncope

If TPS is suspected, it is necessary to conduct an initial examination, including a thorough history taking, examination, and ECG registration; general clinical blood and urine tests; biochemical blood test, troponin test for suspected syncope associated with myocardial ischemia, or D-dimer for suspected PE. A study of blood oxygen saturation and blood gas analysis are necessary if hypoxia is suspected.

Additional testing: Immediate ECG monitoring if arrhythmic syncope is suspected. Echocardiography in the presence of known cardiac pathology, or suspected structural cardiac disease, or syncope secondary to cardiovascular disease. According to indications of ultrasound of internal organs, endocrinological status. The initial examination allows us to identify the cause of fainting in 23% of patients, additional instrumental studies - in 27%.

Does the patient require hospitalization?

50% of patients admitted to emergency departments with SS are hospitalized. Composite assessment of outcomes indicates that in the next 7-30 days after syncope, a fatal outcome is recorded in only 0.8% of patients, and in 6.9% non-fatal serious events are detected. At the same time, another 3.6% experienced unfavorable outcomes after admission.

The main purpose of hospitalization is to prevent fatal outcomes and find the causes of syncope.

The patient management strategy consists of several stages: exclusion of urgent life-threatening pathology (cardiovascular, metabolic, trauma, infections, intoxication); diagnosis of cardiogenic syncope; diagnostic techniques for identifying reflex syncope.

Clinical picture and diagnosis

Three successive periods can be distinguished in the SS. The first - presyncope (lipothymia, presyncope) - is manifested by a feeling of weakness, blurred vision, tinnitus; lasts up to several minutes; Clinical signs include cold sweat and pale skin. The second—fainting itself—is characterized by a complete loss of consciousness, the pulse weakens or disappears, and systolic blood pressure drops to 55–60 mm Hg. Art.; Diffuse muscle weakness with decreased muscle tone and falling are also characteristic. At the moment of fainting, the patient lies motionless, the skeletal muscles are relaxed. The duration of this state is 25–30 s, less often 4–5 minutes; usually accompanied by myoclonic convulsions associated with hypoxia.

The third period is post-syncope. Restoration of consciousness and orientation occurs quickly. However, for an hour after fainting, weakness, dizziness, dry mouth, and anxiety may persist. An attempt to move to a vertical position can lead to repeated fainting.

Complete assessment program for patients with syncope

1. History (family, heart disease, lung disease, metabolic disorders, medication use, information about injuries).

2. Data on previous syncope, examination results.

3. Clarification of the nature of the actions that led to fainting (standing, walking, turning the neck, physical stress, urination, defecation, coughing, swallowing).

4. Clarification of previous events.

5. Determination of features of syncope:

- presence, manifestations and duration of presyncope;

- establishing the position in which the syncope occurred (standing, lying, sitting);

- symptoms during fainting (color and moisture of the skin, frequency and nature of breathing and pulse, convulsive syndrome);

- duration of fainting;

- presence, manifestations and duration of post-syncope.

6. Physical examination with an emphasis on identifying cardiovascular diseases (heart size, cardiac and vascular murmurs, blood pressure, pulse frequency and regularity, differences in pulse filling on both sides in the radial and carotid arteries, signs of heart failure, etc.).

7. Orthostatic test (orthostatic test and/or tilt table test), when fainting is associated with standing up or there is a suspicion of a reflex mechanism of fainting.

8. Test with massage of the carotid sinus in patients over 40 years old.

9. ECG analysis (if possible, during the period (immediately after) fainting, assessment of previous ECGs).

10. Assessment of neurological status with additional research methods (EEG, CT (MRI) of the brain, fundus examination).

11. If cardiogenic syncope is suspected, additional studies are carried out: daily ECG monitoring, echocardiography, electrocardiographic exercise tests, transesophageal pacing, electrophysiological study of the heart according to a special program in specialized departments.

12. Psychological testing for the purpose of diagnosing anxiety, depressive states and identifying the lability of psychological reactions.

Along with Holter 24-hour monitoring, an implantable loop recorder, external devices for ECG recording with the possibility of wireless signal transmission (in real time), smartphone applications, video recording with EEG monitoring (differential diagnosis with an epileptic seizure), electrophysiological study (not used more often) are used. than in 3% of cases).

General principles of treatment

The approach to the treatment of SS is based on risk stratification and, if possible, determining the mechanisms of development of syncope. Comorbid conditions must be taken into account, especially in elderly patients. Polypharmacy, the prescription of cardiovascular, psychotropic (neuroleptics and antidepressants) and dopaminergic drugs also increases the risk of developing syncope and falls. On the contrary, discontinuation or reduction of antihypertensive therapy reduces these risks. The decision to prescribe drugs with negative dromotropic and chronotropic effects should be carefully considered in elderly patients with syncope and a history of falls. Focal neurological events may occur due to hypotension and syncope, even in patients without significant carotid stenosis (so-called hypotension-associated TIAs).

Although the incidence of such events is only 6% among patients with recurrent syncope, their identification is important because misdiagnosis may lead to further reduction of blood pressure with antihypertensive drugs (for example, if focal symptoms are incorrectly correlated with vascular pathology rather than with hypotension), increasing the risk of developing CV and neurological events. According to the accepted consensus, the benefits of reducing doses or discontinuing antihypertensive and psychotropic drugs clearly outweigh the undesirable effects (complications) of elevated blood pressure. Of no small importance, especially with reflex syncope, are lifestyle modification, physical and psychological correction.

Clinical study

Conducted in a group of young people, mainly students. 205 people were interviewed (men - 20.2%, women - 79.8%). Age range from 17 to 36 years, mean age 19.8±1.6 years.

Of the participants, 129 people (62.9%) had CVD, 60 people (29.3%) more than once. Among the most common actions accompanied by fainting, the first place is a sudden rise from the bed (73%), the second place is physical activity (45%), and the third is a change in posture (6.3%). Among the most common factors that provoke fainting, the first place is a stuffy room (85.1%), the second is prolonged standing (27.3%), and the third is pain (24%). At the same time, 93.1% of respondents on the eve of fainting experienced various precursor symptoms: darkening in the eyes, weakness in the legs, malaise, nausea, sweating, and anxiety.

The unconscious period, according to eyewitnesses, was accompanied by a fall in 72.9% of respondents, a change in skin color in 70.5%, and breathing problems in 19.4%. The state of health during the recovery period was assessed as good by 27.6% of respondents, the rest noted the presence of weakness, malaise, palpitations, chills, and sweating. When they fainted, 19 people (13.3%) reported being injured. After fainting, only 28 people (21.9%) sought medical help.

Case from practice

Patient Sh., 25 years old, entered military service under a contract in May 2022. According to the medical examination card of the conscript, upon conscription for compulsory military service the following diagnosis was made: arterial hypertension of the 1st degree, risk 1; minor cardiac anomaly: 1st degree mitral valve prolapse with 1st degree mitral regurgitation; rare ventricular extrasystole, H 0 degree; chronic gastritis; obesity 1st degree; sleep disorder He was found fit for military service with minor restrictions.

After being drafted, some time later he began to complain of periodic headaches, weakness, darkening of the eyes, and stabbing pain in the heart area. For further examination and treatment, he was sent to the therapeutic department of the 1134th VKMC. A detailed laboratory and instrumental examination was carried out and the following pathological abnormalities were identified: during daily ECG monitoring against the background of sinus rhythm, substituting lower atrial complexes and rhythms, episodes of pacemaker migration, frequent episodes of sinoatrial block of the 2nd degree. Type 1, sinus arrhythmia with pauses of more than 1,800 ms, maximum pause of 2,048 ms.

When studying heart rate variability, there is a pronounced functional tension. EchoCG revealed stage 1 mitral and tricuspid regurgitation, grade 2 regurgitation on the pulmonary valve, congenital heart disease (PDA)? Ultrasound of the kidneys revealed diffuse changes in the renal pulse rate. FGDS shows signs of erythematous gastropathy, duodenogastric reflux, and cardia insufficiency. When studying the speed of pulse wave propagation, arterial age is ahead of calendar age.

The results of other examination methods were without deviations from the norm. The patient was consulted by a neurologist, dentist, psychiatrist, associate professor of the Department of Propaedeutics of Internal Diseases of the Grodno State Medical University. Upon discharge from the hospital, recommendations were given on the regimen, nutrition, taking medications and a referral for consultation to the 432nd Main Military Medical Center to verify the diagnosis and determine the category of suitability for military service.

I spent two weeks for examination and treatment in Minsk. The following diagnosis was made: arterial hypertension of the 1st degree, risk 2; 1st degree obesity (BMI 30.16 kg/m2), exogenous-constitutional; MAC: abnormally located chord in the cavity of the left ventricle. Autonomic dysfunction of the sinus node with slowing of sinoatrial conduction in combination with slowing of atrioventricular conduction of a functional (vagus-dependent) nature. Transient 1st degree atrioventricular block. Rare single ventricular and supraventricular extrasystole, N 0 st. Cyst-like formation of the posterior surface of the uvula. Deviation of the nasal septum without difficulty in nasal breathing. Complex myopic astigmatism of 0.5 D of the right eye, 0.75 D of the left eye with myopia of 1.0 D of the right eye and 1.25 D of the left eye in the meridian of the greatest ametropia. Also, during the period of stay in the 432nd GVKMC, the identified changes were not accompanied by SS or significant complaints. He was declared fit for military service with minor restrictions and began service.

However, 10 days later he was taken to the emergency department of the 1134th VKMC with a diagnosis of syncope; bruised wound on the left brow ridge. He was hospitalized in the therapeutic department. In addition to previously established diseases and disorders, bicycle ergometry data revealed an episode of paired ventricular extrasystole. After the treatment, according to the conclusion of the Military Military Commission, he was declared unfit for military service in peacetime. He was discharged for outpatient observation with recommendations for the treatment and prevention of recurrent syncope.