Aripiprazole

- an antipsychotic, one of the brightest representatives of the “new wave” of atypical antipsychotics. Used in practice since 2002.

The safety of the drug was proven even before its use, but the indications for its use gradually expanded as experience was gained.

Initially, the drug was developed for the treatment of “negative” manifestations of schizophrenia, such as apathy, decreased volitional activity, deterioration of cognitive functions (intelligence, memory, attention), “reduction of energy potential,” and decreased emotionality. Data have also emerged on the effectiveness of aripiprazole for non-acute “positive” symptoms of schizophrenia: delusions, hallucinations, mental automatisms, etc.

Later, the drug showed its effectiveness not only in the treatment of schizophrenia. Depression, Bipolar Affective Disorder (manic-depressive psychosis), Alcoholism, Generalized Anxiety Disorder - this is just a small list of mental disorders for which aripiprazole may be effective.

The therapeutic effect of aripiprazole is determined by its specific effect on dopamine, serotonin, histamine and adrenergic receptors in the brain. By acting on these receptors, a cascade of biochemical reactions inside neurons is triggered, which leads to the restoration of mental functions impaired by the disease.

Instructions for use ARIPRAZOLE

When treated with antipsychotics, improvement in the patient's clinical condition may take from several days to several weeks. During this period, patients should be closely monitored.

Suicidal tendencies

The onset of suicidal behavior is common in patients with psychotic illnesses and mood disorders, and in some cases has been observed shortly after initiation of antipsychotics or switching from one antipsychotic to another antipsychotic, including treatment with aripiprazole. Treatment with antipsychotics should be accompanied by careful monitoring of patients at increased risk.

It is known that there is no increased risk of suicidality with aripiprazole compared with other antipsychotics.

Cardiovascular disorders

Aripiprazole should be used with caution in patients with a history of cardiovascular disease (myocardial infarction or coronary artery disease, heart failure or conduction disturbances), cerebrovascular disorders, conditions that make patients prone to hypotension (dehydration, hypovolemia, use of antihypertensive drugs) or hypertension , including progressive or malignant hypertension.

Cases of venous thromboembolism (VTE) have been observed during treatment with antipsychotics.

Since acquired risk factors for VTE are often observed in patients taking antipsychotics, all possible risk factors for VTE should be identified before and during treatment with aripiprazole and all preventive measures should be taken.

QT prolongation

As with other antipsychotics, aripiprazole should be used with caution in patients with a family history of QT prolongation.

Tardive dyskinesia

If symptoms of tardive dyskinesia occur in a patient taking aripiprazole, consider reducing the dose of the drug or discontinuing treatment. These symptoms may become temporarily worse or even occur after stopping treatment.

Other extrapyramidal symptoms

Akathisia and parkinsonism have been observed in children with the use of aripiprazole. If signs of other extrapyramidal symptoms appear, dose reduction should be considered and the patient's condition should be closely monitored clinically.

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS)

NMS is a complex of symptoms associated with the use of antipsychotics that can potentially be fatal.

Clinical manifestations of NMS include hyperpyrexia (extremely high body temperature), muscle rigidity, altered mental status, and signs of autonomic nervous system disorder (irregular pulse or unstable blood pressure, tachycardia, increased sweating, and cardiac arrhythmia). Additional features may include elevated creatine kinase levels, myoglobinuria (rhabdomyolysis), and acute renal failure. However, isolated cases of increased creatine kinase levels and rhabdomyolysis, not necessarily associated with NMS, have also been observed. If the patient develops symptoms of NMS or an unexplained very high body temperature without additional clinical manifestations of NMS, take all antipsychotic medications, incl. aripiprazole should be discontinued.

Epileptic seizures

Infrequent cases of epileptic seizures have been observed during treatment with aripiprazole. Therefore, aripiprazole should be used with caution in patients with a history of epilepsy or conditions associated with epileptic seizures.

Elderly patients with psychosis due to dementia

Increased mortality:

When using aripiprazole in elderly patients with psychosis due to Alzheimer's disease, the risk of death is increased. Although the causes of death varied, most were cardiovascular (eg, heart failure, sudden death) or infectious (eg, pneumonia) in nature.

Adverse reactions of a cerebrovascular nature:

in elderly patients with psychosis due to Alzheimer's disease, adverse reactions of the cerebrovascular type were observed (for example, stroke, transient ischemic attack), incl. with fatal outcome. A strong relationship was noted between drug doses and the occurrence of cerebrovascular-type adverse reactions in patients taking aripiprazole.

Aripiprazole is not indicated for the treatment of psychosis associated with dementia.

Hyperglycemia and diabetes mellitus

Hyperglycemia, in some cases extremely severe and associated with ketoacidosis or hyperosmolar coma, incl. with a fatal outcome, was observed in patients taking atypical antipsychotics, incl. aripiprazole. Risk factors for severe complications include obesity and a family history of diabetes. There is no accurate comparative assessment of the risks of adverse reactions associated with hyperglycemia in patients taking aripiprazole and other atypical antipsychotics. Patients taking any antipsychotics, including aripiprazole, should be closely monitored for symptoms of hyperglycemia (such as polydipsia, polyuria, polyphagia, and weakness), and patients with diabetes mellitus or risk factors for diabetes mellitus should be regularly monitored for increased glucose concentrations.

Hypersensitivity

As with other medicines, hypersensitivity reactions may occur when using aripiprazole.

Weight gain

Patients with schizophrenia and bipolar mania often experience weight gain due to comorbidities, use of antipsychotic medications known to cause weight gain, and lack of a healthy lifestyle; this phenomenon can lead to serious complications. During treatment with aripiprazole, cases of weight gain have generally been observed in patients with significant risk factors, such as diabetes mellitus, a thyroid disorder, or a history of pituitary adenoma.

Aripiprazole does not cause clinically significant weight gain in adults.

Dysphagia

Antipsychotics, including aripiprazole, may cause esophageal motility disorders and aspiration of gastric contents. Aripiprazole and other antipsychotics should be used with caution in patients at increased risk of aspiration pneumonia.

Pathological gambling

Pathological gambling has been reported in patients prescribed aripiprazole, regardless of whether they had a history of gambling. Patients with a history of pathological gambling may be at increased risk and should be closely monitored.

Lactose

The drug contains lactose. Patients with rare hereditary disorders such as galactose intolerance, lapp lactase deficiency or glucose-galactose malabsorption should not take Ariprazole.

Patients with comorbid ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder)

Despite the high incidence of comorbid ADHD in bipolar I disorder, there are very limited data on the safety of concomitant use of aripiprazole and stimulants, and extreme caution is warranted when coadministering these drugs.

Use in pediatrics

Aripiprazole at this dosage is not recommended for use in children.

Impact on the ability to drive vehicles and operate machinery

Aripiprazole, like other antipsychotics, can affect the ability to drive vehicles due to adverse reactions from the nervous system and the organ of vision. During treatment, it is recommended to refrain from driving vehicles or operating other mechanisms until the individual sensitivity of patients to the drug is known.

Ariprizole® (Aripiprazole)

The therapeutic effect of antipsychotic drugs develops over several days to several weeks. During this period, it is necessary to monitor the patient's condition.

Suicide attempts

The phenomenon of suicidal behavior is characteristic of psychosis and mood swings, in some cases it is observed immediately after the start or change of treatment with antipsychotic drugs, including treatment with aripiprazole. When treating with antipsychotic drugs, it is necessary to monitor patients at increased risk.

The results of one epidemiological study showed that patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder did not experience an increased risk of suicidality when treated with aripiprazole compared with other antipsychotic drugs.

There are insufficient clinical data to assess this risk in younger patients (<18 years of age), but there is evidence to suggest that the risk remains after 4 weeks of treatment with antipsychotic drugs, including aripiprazole.

Cardiovascular diseases

Aripiprazole should be used with caution in patients with cardiovascular disease (myocardial infarction, coronary artery disease, heart failure, history of cardiac conduction disorders), cerebrovascular accidents, conditions predisposing to arterial hypotension (dehydration, hypovolemia, therapy with antihypertensive drugs), or hypertension, including essential or malignant.

Cases of venous thromboembolism have been reported with the use of antipsychotic drugs. Since patients treated with antipsychotic drugs often have acquired risk factors for the development of venous thromboembolism, it is necessary to determine all possible risk factors for the development of venous thromboembolism before and during treatment with Ariprizole® with preventive measures.

Conduction disorders

In clinical studies of aripiprazole, the incidence of QT prolongation was comparable to the placebo group. Aripiprazole, like other antipsychotic drugs, should be used with caution in patients with a family history of QT prolongation.

Tardive dyskinesia

In clinical studies lasting less than 1 year, infrequent cases of dyskinesia requiring urgent treatment were observed during treatment with aripiprazole. If a patient develops signs and symptoms of tardive dyskinesia while being treated with Ariprizole, dose reduction or discontinuation of treatment should be considered. Symptoms of dyskinesia may temporarily increase or even appear for the first time after discontinuation of therapy.

Other extrapyramidal disorders

Akathisia and parkinsonism were observed in clinical studies of aripiprazole in children. If signs and symptoms of other extrapyramidal disorders occur, consider reducing the aripiprazole dose and monitor the patient.

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS)

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome is a potentially life-threatening constellation of symptoms associated with the use of antipsychotic drugs. In clinical studies, rare cases of NMS were observed during treatment with aripiprazole, which is manifested by hyperpyrexia, muscle rigidity, mental disturbances and instability of the autonomic nervous system (irregular pulse and blood pressure, tachycardia, sweating, cardiac arrhythmia).

In addition, in some cases, increased CPK activity, myoglobinuria (rhabdomyolysis) and acute renal failure occur. If symptoms of NMS or unexplained fever occur, all antipsychotics, including Ariprizole®, should be discontinued.

Convulsions

In clinical studies, infrequent cases of seizures were observed during treatment with aripiprazole. Therefore, aripiprazole should be used with caution in patients with a history of seizures and a risk of developing them.

Psychoses associated with senile dementia

In three placebo-controlled clinical trials of aripiprazole in elderly patients (mean age 82.4 years, age range 56-99 years) with psychosis due to Alzheimer's disease, an increased risk of death was observed compared with the placebo group.

The mortality rate with aripiprazole was 3.5% compared with 1.7% in the placebo group. Although the causes of death varied, the underlying causes of most deaths were either cardiovascular disorders (including heart failure, sudden death) or infection (including pneumonia).

During these same clinical studies, cerebrovascular adverse reactions (including stroke, transient ischemic attack), including death, were reported in elderly patients (mean age 84 years, age range 78-88 years).

Overall, 1.3% of patients treated with aripiprazole experienced cerebrovascular adverse events compared with 0.6% of patients treated with placebo. This difference was not statistically significant. However, one of these fixed-dose studies of aripiprazole found a significant dose interaction with cerebrovascular adverse reactions.

Ariprizole® is not recommended for use in patients with psychosis due to dementia.

Hyperglycemia and diabetes mellitus

Hyperglycemia, in some cases severe and accompanied by ketoacidosis or hyperosmolar coma with a fatal outcome, has been noted in patients taking atypical antipsychotics. The relationship between atypical antipsychotics and hyperglycemic-type disorders remains unclear.

In clinical studies of aripiprazole, there was no significant difference in the incidence of adverse reactions involving hyperglycemia (including diabetes) or changes in laboratory glycemic values compared with the placebo group.

Patients diagnosed with diabetes mellitus while taking atypical antipsychotics should regularly monitor their blood glucose concentrations. Patients who have risk factors for developing diabetes mellitus (obesity, a family history of diabetes mellitus) when taking atypical antipsychotics should have their blood glucose levels determined at the beginning of the course and periodically while taking the drug.

In patients taking atypical antipsychotics, constant monitoring of symptoms of hyperglycemia (increased thirst, frequent urination, polyphagia, weakness) is necessary. Particular attention should be paid to patients with diabetes mellitus and risk factors for its development.

Hypersensitivity

As with other medications, hypersensitivity reactions in the form of allergic symptoms may occur when taking aripiprazole.

Weight gain

Weight gain is commonly observed in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar mania due to the development of comorbidities, the use of antipsychotic drugs that cause weight gain, and unhealthy lifestyle choices that can lead to acute complications.

Case reports of weight gain have been received during the post-marketing period in patients taking aripiprazole. Typically, these adverse reactions were observed in patients with significant risk factors, such as diabetes mellitus, thyroid disease or pituitary adenoma. In clinical studies, aripiprazole did not cause clinically significant weight gain.

In clinical studies of adolescent patients with bipolar mania treated with aripiprazole, body weight increased after 4 weeks of treatment. Continuous monitoring of body weight is necessary in adolescent patients with bipolar mania. If weight gain is clinically significant, the dose of aripiprazole should be reduced.

Dysphagia

When using antipsychotics, there have been cases of disturbances in esophageal peristalsis and, as a consequence, aspiration pneumonia. The drug should be prescribed with caution to patients with risk factors for developing aspiration pneumonia.

Pathological attraction to gambling

During the post-marketing period, there have been reports of pathological gambling in patients taking aripiprazole, regardless of whether these patients had a history of pathological gambling.

Patients with a history of pathological gambling may be at increased risk of developing this disorder and should be closely monitored while using aripiprazole.

Lactose

The drug Ariprizole® contains lactose, so it is not recommended for patients with rare hereditary diseases associated with galactose intolerance, lactase deficiency or glucose-galactose malabsorption.

Patients with comorbid attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

Despite the high incidence of co-occurrence of bipolar I disorder and ADHD, there are very limited data on the safety of the concomitant use of aripiprazole and psychostimulants, so caution should be exercised if they are used together.

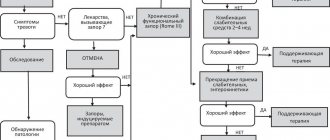

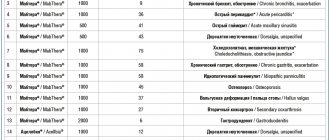

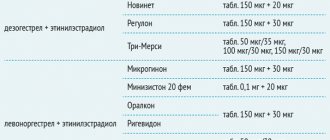

Issues of tolerability and safety of aripiprazole therapy

The risk of weight gain in the form of pharmacogenic weight gain (more than 5-7% of baseline during treatment), type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and dyslipidemia with aripiprazole treatment is similar to placebo during 6-month follow-up [51]. According to [16, 17, 27, 48], the risk of weight gain is minimal with aripiprazole and ziprasidone compared to other SGAs. In addition, studies [21, 35, 36, 49] show a significant reduction in body weight within 6 months of treatment when switching to aripiprazole in patients who had gained weight during previous therapy with other SGAs, as well as normalization of lipoprotein and triglyceride levels. In a study by Kim SW et al (2009), when switching to aripiprazole after treatment with SGAs during 26-week therapy, the following results were obtained: a significant decrease in total cholesterol levels (186.3 to 174.6 mg/dL); a significant increase in HDL (47.9 to 53.2 mg/dl) and a significant decrease in body weight (67.03 to 65.79 kg).

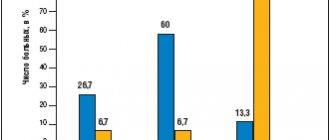

A study [33] of acute aripiprazole therapy found no difference from placebo in weight gain in patients with schizophrenia (maximum figure was 0.9 kg). Similar data were obtained in [20]: with various therapeutic strategies for prescribing aripiprazole, body weight gain did not exceed 1.7 kg during 8-week treatment, and pharmacogenic weight gain did not exceed 5% of the number of subjects examined. Results from a 26-week study of aripiprazole showed a 1.26 kg reduction in body weight and no significant difference from baseline in fasting glucose levels and no effect on lipid parameters. In addition, changes in body weight and glucose levels were less pronounced compared with placebo [51]. According to Kasper S. et al (2003), a comparative study of 12 months of therapy with aripiprazole and haloperidol found a slight increase in body weight, which was observed in patients with underweight (BMI <23 kg/m2). At the same time, in obese patients (BMI>27 kg/m2) a decrease in body weight was observed. At the same time, transferring a patient to aripiprazole in order to minimize metabolic disorders requires the inclusion of a comprehensive program for weight loss as part of the general improvement of the patient’s lifestyle (dietary recommendations, moderate physical activity, smoking cessation, etc.) [15, 37]. The risk of developing INDIS (not directly related to weight gain) is low when treated with aripiprazole, risperidone, ziprasidone and high-potency FGAs [27, 52, 56]. Although prospective randomized clinical trials (RCTs) did not show significant differences in antipsychotic treatment, patients on aripiprazole in the naturalistic STAR study had significantly less hyperglycemia compared with quetiapine, risperidone and olanzapine [17, 19, 23]. A comparative 4-week study of aripiprazole, risperidone and placebo showed a minimal increase in body weight from baseline in dynamics in all three groups: aripiprazole 20 mg - 1.2 kg aripiprazole 30 mg - 0.8 kg, risperidone 6 mg - 1 .5 kg These values were significantly different from those in the placebo group, in which a decrease in body weight of 0.3 kg was noted during the study period. The frequency of pharmacogenic weight gain was significantly higher in all treatment options compared to placebo: placebo - 2% ; aripiprazole 20 mg - 13% (p = 0.004); aripiprazole 30 mg - 9% (p = 0.04); risperidone 6 mg - 11% (p = 0.03) [8]. In a comparative study by Fleischhaker WW et al (2008) of aripiprazole and olanzapine, by week 26, 40% of patients taking olanzapine experienced significant weight gain compared with 21% of patients in the aripiprazole group. The statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) NNT (95% CI) was 5.2 (3.5-10.2). At week 52, similar results were observed (olanzapine 43%; aripiprazole 21%; NNT [95% CI], 4.5 [3.1-8.3]). The mean change in body weight from baseline was statistically significantly different between treatment groups (all p < 0.001 except day 4) in favor of aripiprazole. The mean change in body weight at week 26 was +4.30 kg in the olanzapine group and +0.13 kg in the aripiprazole group (p < 0.001), and at week 52 it was +4.74 kg versus +0.32 kg, respectively. The authors found more patients with increases in fasting total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and triglycerides (all p < 0.001) in the olanzapine group. In addition, a significant number of patients in the olanzapine group compared with the aripiprazole group experienced new-onset increases in total cholesterol, triglycerides, and fasting LDL. The average change in these indicators was also in favor of aripiprazole. There were no between-group differences in the percentage of patients with clinically significant levels of LDL cholesterol (p = 0.383), fasting glucose (p = 0.810), or fasting glycated hemoglobin (p = 0.056). In another 52-week comparative study [22], weight gain with olanzapine was 2.54 kg versus 0.04 kg with aripiprazole (p < 0.001). Among study completers, mean weight gain was 3.02 kg with olanzapine and 0.57 with aripiprazole (p = 0.004). More patients experienced pharmacogenic weight gain during olanzapine therapy (24% vs. 10%, p = 0.008). In addition, a similar trend was found - an increase in the number of such patients in each group, with persistent differences in favor of olanzapine. In terms of differences in drug effects on biochemical parameters, olanzapine was found to have greater effects on lipid, cholesterol, and LDL levels than aripiprazole. At week 52, patients in the aripiprazole group had modest improvements in HDL cholesterol levels and more favorable changes in triglyceride levels, which did not reach significance compared with olanzapine. Among patients with normal baseline fasting glucose values, potentially clinically significant values were observed to a greater extent in the olanzapine group compared with aripiprazal (27% vs. 16% p = 0.127), but no significant differences were found. However, it should be noted that the data obtained in the last 2 studies require a more balanced assessment and additional verification, since the analysis of biochemical parameters was carried out using the method of transferring the data of the last measurement forward. This method is quite widely used in statistical data processing, but significantly reduces the degree of their reliability.

When treated with aripiprazole, the incidence of metabolic syndrome is significantly lower than with a number of SGAs [24, 41, 42]. In addition, with timely detection of MS and transfer of the patient to aripiprazole, a reduction in MS symptoms was observed in 50% of patients after 3 months of therapy. According to a number of studies, the effect of aripiprazole on metabolic parameters is similar to those of ziprasidone. Short-term studies including 932 patients treated with aripiprazole, 201 patients treated with haloperidol, and 416 patients taking placebo found the following results: in 8% of patients taking aripiprazole, body weight increased more than 7% of the original, and the average increase in weight body weight when using all dosages was 0.71 kg and was not significantly different from the haloperidol group (0.56 kg), as indicated by Marder SR et al (2003). Marcus RN et al (2009) conducted a short-term placebo-controlled trial of aripiprazole in children and adolescents with autism. They used fixed dosages of aripiprazole - 5, 10 and 15 mg. At the end of 8 weeks, the increase in body weight in the placebo group was +0.3 kg; at dosages of aripiprazole 5 mg/day - 1.3 kg; 10 mg/day - 1.3 kg and 15 mg/day - 1.5 kg. The difference between the values in patients taking placebo and aripiprazole was significant (p < 0.05).

Thus, the data presented show the presence of a favorable endocrine safety profile and tolerability of aripiprazole, which distinguishes it favorably from many representatives of both FGAs and SGAs. In addition to the use of aripiprazole as a drug of choice for relief, and especially for long-term anti-relapse therapy, the possibility of transferring patients with mental disorders to taking the drug in the presence of NHP and metabolic disorders that developed during the use of FGAs and SGAs, as well as augmentation of aripiprazole to therapy with drugs with high prolactogenic activity. It should also be emphasized that the data obtained in clinical studies are often only to a certain extent useful in everyday clinical practice [12], since most often they relate to a rather limited range of problems of the drug under study. Of course, when prescribing any psychopharmacological drug, it is necessary to take into account not only the full range of its effectiveness and safety, but also the individual characteristics of the patient (soil factors, family history, etc.). Only with this approach can optimal treatment results be achieved in patients with mental disorders, which is a priority task for psychiatrists.

Bibliography

1. Gorobets L.N. Neuroendocrine dysfunctions and antipsychotic therapy. - M.: Publishing House "Medpraktika-M", 2007. - 312 p. 2. Gorobets L.N. Diagnosis, correction and prevention of neuroendocrine dysfunctions in patients with schizophrenia in the conditions of modern antipsychotic pharmacotherapy // Biological methods of therapy of mental disorders. Evidence-based medicine - clinical practice / Ed. S.N. Mosolova. - M., 2012. - P. 830-862. 3. Dratku L., Olowu M., Khorami M. et al. The use of aripiprazole in the treatment of exacerbation of schizophrenia in male patients in a city hospital: effectiveness, feasibility and risk // Social and Clinical Psychiatry. - T. 17. - Issue. 3. - M., 2007. - P. 61 -66. 4. Kanaeva L.S. Possibilities of using aripiprazole in the formation and maintenance of remissions in schizophrenia (literature review] // Psychiatry and psychopharmacotherapy. Journal named after P.B. Gannushkin. - 2009. - Volume 11, No. 4. - P. 30 -35. 5. Lyubov E. .B. Aripiprazole (Abilify): rational choice in the treatment of schizophrenia // Social and clinical psychiatry. - T. 18. - Issue 4. - M., 2008. - P. 94 - 103. 6. Mazo G.E. Prospects for the development of endocrinological psychiatry // Modern advances in the diagnosis and treatment of endogenous disorders. - St. Petersburg, 2008. - pp. 210-224. 7. Mosolov S.N. Antipsychotic pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia: from scientific data to clinical recommendations // Biological methods of therapy mental disorders. Evidence-based medicine - clinical practice / Edited by S.N. Mosolov. - M., 2012. - P. 11-60. 8. Potkin S.G., Sakha A.R., Kuyava M.J. and others. Aripiprazole, an atypical antipsychotic with a new mechanism of action and risperidone in comparison with placebo in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder // Social and clinical psychiatry. - T. 17. - Issue. 2. - M., 2007. - P. 72 -79. 9. Fleischhacker V.V., McQuaid R.D., Marcus R.N. et al. Double-blind, randomized study aimed at comparing aripiprazole and olanzapine in patients with schizophrenia // Social and clinical psychiatry. - T. 19. - Issue. 3. - M., 2009. - P. 47-55. 10. Chrzanowski V.K., Markus R.N., Torbanes A., et al. Efficacy of long-term aripiprazole therapy in patients with acute relapse of schizophrenia or chronic stable illness: an open, 52-week comparison with olanzapine. Social and Clinical Psychiatry. - T. 18. - Issue. 1. - M., 2008. - P. 62-69. 11. Shmukler A.B. Aripiprazole: new possibilities of antipsychotic therapy // Social and clinical psychiatry. - T. 16. - Issue. 4. - M., 2006. - P. 96-102. 12. Shmukler A.B. Evidence-based research in psychiatry: analysis of practical significance // Psychiatry and psychopharmacotherapy. Journal named after P.B. Gannushkina. - 2012. - Volume 14. No. 5.- P. 4-13. 13. Allison DB, Casey DE Antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a review of the literature // J. Clin. Psychiatry. - 2001. - Vol. 62. - R. 22-31. 14. Allison DB, Fontaine KR, Heo M. et al. The distribution of body mass index among individuals with and without schizophrenia // J. Clin. Psychiatry. - 1999. - Vol. 60. - R. 215-220. 15. American Psychiatric Association: Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition // Am. J. Psychiatry. - 2004. - Vol. 161. - P. 1-56. 16. Argo TR, Carnahan RM, Perry PJ Aripiprazole, a novel atypical antipsychotic drug // Pharmacotherapy. - 2004. - Vol. 24. - P. 212-228. 17. Blonde L, Kan HJ, Gutterman EM et al. Predicted risk of diabetes and coronary heart disease in patients with schizophrenia: aripiprazole versus standard of care // J. Clin. Psychiatry.. - 2008. -Vol. 69. - P. 741-748. 18. Burris KD, Molski TF, Xu C. et al. Aripiprazole, a novel antipsychotic, is a high affinity partial agonist at human dopamine D2receptors // J.Pharmacol.Exp. Ther. — 2002.- Vol. 302. - P. 381-389. 19. Bushe CJ Leonard BE Blood glucose and schizophrenia: a systematic review of prospective randomized clinical trials // J. Clin. Psychiatry. -2007. -Vol. 68. - P. 1682-1690. 20. Casey DE, Carson WH Saha AR et al. Switching patients to aripiprazole from other antipsychotic agents: a multicenter randomized study // Psychopharmacology (Berll - 2003. - 166: 391-399. 21. Christensen WK, Marcus RN, Torbeyns A. et al. Effectiveness of long-termaripiprazole therapy in patients with acutely relapsing or chronic stable schizophrenia: a 52-week, open-label comparison with olanzapine // Psychopharmacol. - 2006. - Vol. 113. - P. 148-153. 22. Chrzanowski WK, Marcus RN et al. Effectiveness of long-term aripiprazole therapy in patients with acutely relapsing or chronic, stable schizophrenia: a 52-week, open-label comparison with olanzapine // Psychopharmacology (Berl). -2006. - Dec; 189(2). - 259- 266. 23. Corey-Lisle P., Kolotkin RL, Crosby RD et al. Changes in Weight and Weight-Related Quality of Life in Aripiprazole Versus Standard of Care Treatment (The STAR Trial] // American Psychiatric Association 159th Annual Meeting, Toronto , Canada. May 20-25. - 2006. - Poster NR334. 24. De Hert M., Hanssens L., van Winkel R. et al. A case series: evaluation of the metabolic safety of aripiprazole // Schizophr. Bull. - 2007. - Vol. 33. - P. 823-830. 25. El-Sayeh HG, Morganti C. Aripiprazole for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. - 2006. - Vol. 2. - CD 004578. 26. Fleischhacker WW, Hofer A., Hummer M. Managing Schizophrenia: The Compliance Challenge.Second edition. - 2008. - p. 50. 27. Gardner DM, Baldessarini RJ, Waraich P. Modern antipsychotic drugs: a critical overview // CMAJ. — 2005. -Vol. 172; N 13. -P. 1703-1711. 28. Haddad PM, Sharma SG Adverse effects of atypical antipsychotics: differential risk and clinical implications // CNS Drugs. - 2007. - Vol. 21. - P. 911-936. 29. Halbreich U., Kahn LS Hormonal aspects of schizophrenias: an overview // Psychoneuroendocrinology. - 2003. - P. 16-28. 30. Haupt DW Differential metabolic effects of antipsychotic treatments // European Neuropsychopharmacology. - 2006. - No. 16. - P. 149-155 31. IDF Epidemiology Task Force Consensus. Group. The metabolic syndrome is a new worldwide definition //Lancet. - 2005. 32. Jordan S., Koprivica V., Chen R. et al. The antipsychotic aripiprazole in a potent, partial agonist at the human 5-HT1A receptor // Eur. J. Pharmacol. - 2002. - Vol. 441 - P. 137-140. 33. Kane JM, Carson WH, Saha AR et al. Efficacy and safety of aripiprazole and haloperidol versus placebo in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder // J.Clin. Psychiatry. - 2002. - 63: 763 - 771. 34. Kasper S., Lerman MN, VcQuade RD et al. Efficacy and safety of aripiprazole versus haloperidol for long-term treatment maintenance following acute relapse of schizophrenia // Int. J. Psychopharmacol.- 2003.- Vol. 6- P. 325-337. 35. Kerwin R., L'Italien G., Hanssens L. et al. Effectiveness of Aripiprazole Versus Standard of Care Treatment in Patients With Schizophrenia: The Schizophrenia Trial of Aripiprazole (STAR) Study //19th European College of Neuropsychopharmacology (ECNP) Congress, Paris, France, September 16-20, 2006. 36. Kerwin R. , Millet B., Herman E. et al. A multicentre, randomized, naturalistic, open-label study between aripiprazole and standard of care in the management of community treated schizophrenic patients. Schizophrenia Trial of Aripiprazole: (STAR) study // Eur. Psychiatry. - 2007. - Vol. 22. - P. 433-443. 37. Kim SH, Ivanova O., Abbasi FA et al. Metabolic impact of switching antipsychotic therapy to aripiprazole after weight gain: a study pilot // J. Clin. Psychopharmacol.- 2007. - Vol. 27. - P. 365-368. 38. Kim SW et al. Effectiveness of switching to aripiprazole from atypical antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia // Clinical Neuropharmacology. - 2009-32 (5); R. 243-249. 39. Kubo M., Mizooku Y., Osumi T. Development and validation of an LC-MS/MS method for the quantitative determination of aripiprazole and its metabolite, OPC14857, in human plasma // J. Chromatogr. B. -2005. - 822; 294-299. 40. Lieberman JA Dopamine partial agonists: a new class of antipsychotic // CNS Drugs. - 2004. - Vol. 18. - P. 251-267. 41. L'Italien GJ, Casey DE, Kan HJ et al. Comparison of metabolic syndrome incidence among schizophrenia patients treated with aripiprazole versus olanzapine or placebo // J. Clin. Psychiatry. -2007. - Vol. 68. -P. 1510-1516. 42. L'ltalien G., Hanssens L., Marcus R. et al. Metabolic Effects of Aripiprazole Versus Standard of Care (The STAR Trial] // American Psychiatric Association 159th Annual Meeting, Toronto, Canada. May 20-25, 2006. Abstract NR391. 43. Luft B., Taylor D. A review of atypical antipsychotic drugs versus conventional medication in schizophrenia // Expert Opin. Pharmacother. - 2006. - Vol. 7. - P. 1739-1748. 44. Madhusoodanan S., Parida S., Jimenez C. Hyperprolactinemia associated with psychotropics - a review // Hum. Psychopharmacol. Clin. Exp. - 2010. - 25; 281-297. 45. Marcus RN, Owen R., Kamen L. et al. A placebo-controlled, fixed-dose study of aripipazole in children and adolescents with irritability associated with autistic disorder // J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. - 2009. - Nov.; 48(11): 1110-9. 46. Marder SR, McQuade RD, Stock E. et al. Aripiprazole in the treatment of schizophrenia: safety and tolerability in short-term, placebo-controlled trials // Schizophr. Res. - 2003. - 61: 123-136. 47. McEvoy JP, Meyer JM, Goff DC et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia: baseline results from the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia trial and comparison with national estimates from NHANES III // Schizophr. Res. — 2005. -80: 19-32. 48. Newcomer JW Second-generation (atypical) antipsychotics and metabolic effects: a comprehensive literature review // CNS Drugs. -2005. - Vol. 19. - P. 1-93. 49. Newcomer JW, Campos JA, Marcus RN et al. A multicenter, randomized, doubleblind study of the effects of aripiprazole in overweight subjects with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder switched from olanzapine // J. Clin. Psychiatry. -2008. - Vol. 69. - P. 1046-1056. 50. Newcomer JW, Haupt DW The metabolic effects of antipsychotic medications // Can. J. Psychiatry. - 2006. - 51:480-491. 51. Pigott TA, Carson WH, Saha AR et al. Aripiprazole for the prevention of relapse in stabilized patients with chronic schizophrenia: a placebo-controlled 26-week study // J. Clin. Psychiatry. — 2003.- Vol. 64. No. 9.- P. 1048-1056. 52. Ramaswamy K., Masand PS, Nasrallah HA Do certain atypical antipsychotics increase the risk of diabetes? A critical review of 17 pharmacoepidemiologic studies // Ann. Clin. Psychiatry. — 2006. -Vol. 18.- P. 183-194. 53. Shim J.-Ch., Shin J.-G., Kelly D.L. et al. The partial dopamine agonist aripiprazole as adjunctive therapy for antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia: a placebo-controlled study. Modern Therapy of Mental Disorders. - No. 3. - M. - 2008. - P. 33-39. 54. Stahl SM Dopamine system stabilizers, aripiprazole, and the next generation of antipsychotics, part 1, “Goldilocks” actions at dopamine receptors // J. Clin. Psychiatry.- 2001. - Vol. 62. - P. 841-42. 55. Swainston HT, Perry CM Aripiprazole: a review of its use in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder // Drugs. -2004. - 64: 1715-1736. 56. van Winkel R., De Hert M., Wampers M/ et al. Major changes in glucose metabolism, including new-onset diabetes, within 3 months after initiation of or switch to atypical antipsychotic medication in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder // J. Clin. Psychiatry. -2008. - Vol. 69. P. 472-479. 57. Yokoi F, Grunder G, Biziere K et al. Dopamine D2 and D3 receptor occupancy in normal humans treated with the antipsychotic drug aripiprazole (OPC 14597): a study using positron emission tomography and (11C) raclopride // Neuropsychopharmacology. - 2002. - 27: 248-259.

The problems of aripiprazole therapy drug tolerance (endocrinological aspect)

Gorobets LN

Moscow Research Institute of Psychiatry [Russia]

SUMMARY : Introduced review has dedicated to one of the psychopharmacological significant problems - endocrinological aspects of drug tolerance by second-generation antipsychotics (SGA). Below presents the data of comparative studies by influence of separate antipsychotics compared to aripiprazole on levels of serum prolactin, high- and low-density lipoproteins (HDL and LDL), glucose and mass of a body change in the patients with mental illness. There were shown the aripiprazole preferences in respect of hyperprolactinemia (HP) and metabolic disorders.

KEY WORDS : aripiprazole, hyperprolactinemia, weight gain, high- and low-density lipoproteins (HDL and LDL), glucose level