Mechanism of action and pharmacokinetics

Mirtazapine has a tetracyclic structure and is classified as a noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant (NSSA). Acting as an antagonist of “inhibitory” central presynaptic α-2 autoreceptors, interfering with negative feedback and causing the release of norepinephrine. Blockade of heteroreceptors, α-2 receptors contained in serotonin neurons, enhances the release of serotonin, increasing the interaction between serotonin and 5-HT1 receptors and thereby promoting the anxiolytic effect of mirtazapine. Mirtazapine also acts as a weak antagonist of 5-HT1 receptors and as a strong antagonist of 5-HT2 (especially subtypes 2A and 2C) and 5-HT3 receptors. Blockade of these receptors may explain the lower incidence of side effects such as anxiety, insomnia and nausea, which are common with SSRI antidepressants. Mirtazapine also exhibits significant antagonism at histamine H1 receptors, resulting in sedation. Mirtazapine does not affect the reuptake of norepinephrine and serotonin, and also has minimal activity at dopaminergic and muscarinic receptors.

- Bioavailability about 50%

- Equilibrium concentration in the blood is established after 3–4 days

- Half-life 20-40 hours

- Actively metabolized in the liver by demethylation and oxidation followed by conjugation

- Metabolized by cytochromes P450 2D6, P450 1A2 and P450 3A4.

- Eating does not affect absorption

Mirtazapine - a new generation antidepressant

S.G. Burchinsky, Institute of Gerontology of the Academy of Medical Sciences of Ukraine, Kiev

Summary

The article describes the mechanism of action of the new generation antidepressant, Mirtazapine, and provides a comparative description of the effects of this drug with other antidepressants widely used in clinical practice. The use of Mirtazapine in geriatric practice and issues of drug safety are discussed separately.

Keywords

depressive disorders, Mirtazapine.

One of the leading problems of modern psychiatry is depressive disorders, taking into account both the frequency of their development in the modern population (up to 10%), and their social, economic and psychological significance, as well as their role in the disability of the population. Accordingly, the search for highly effective tools for pharmacotherapy of depression—new drugs from the antidepressant group—becomes especially relevant in this regard.

Antidepressants are currently one of the most intensively developed groups of psychotropic drugs. For example, in the USA they occupy first place both in the number of new compounds studied and in the amount of capital investment in the creation of new drugs [19].

Considering the significance of depressive disorders in terms of their colossal role in the structure of morbidity, disability, and the economic costs of them in developed countries, the evolution of the clinical picture of depression observed over the past decades is of particular relevance, namely:

- an increase in the number of atypical, erased, comorbid clinical forms;

- increased frequency and severity of relapses;

- increased resistance to therapy with conventional antidepressant drugs - tricyclics (TADs) and serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

In addition, it is necessary to separately highlight the tendency towards increased polypharmacy in the treatment of depression due to an increase in the number of psycho- and somatotropic drugs taken in parallel, as well as a deterioration in the tolerability of many first-generation drugs, especially TAD [4, 31].

In this regard, in psychopharmacology there arose a need to develop new antidepressants, on the one hand, with an expanded mechanism of action, including an effect on various neurotransmitter systems, and, accordingly, with a wider range of clinical and pharmacological effects, and on the other hand, retaining a pronounced selectivity of action on individual links of synaptic structural and functional organization and, therefore, characterized by a high level of safety.

In this regard, drugs from the antidepressant group with a fundamentally different mechanism of action compared to representatives of the first generations deserve special attention, i.e. drugs with an effect not on the monoamine reuptake system, but on various receptor structures. One of these drugs is mirtazapine, a four-cyclic derivative, a noradrenergic and selective serotonergic antidepressant (NaSSA), the creation of which marked a new stage in the development of the pharmacology of these drugs.

Mirtazapine is an antidepressant with a unique mechanism of action. Unlike TAD and SSRI drugs, it does not affect the reuptake of serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine. This drug selectively blocks alpha-2 auto- and heteroadrenergic receptors, as well as serotonin 5-HT-2 and 5-HT-3 receptors.

Why is this mechanism of action interesting from the point of view of pharmacotherapy of depression?

As is known, activation of alpha-2-autoadrenergic receptors located on the presynaptic terminals of adrenergic neurons, through a feedback mechanism, helps to reduce the release of norepinephrine from the synaptic nerve ending and, accordingly, inhibit the implementation of adrenergic processes in the brain. At the same time, alpha-2-heteroadrenergic receptors are located on the terminals of serotonergic neurons, and their activation also weakens serotonergic effects in the central nervous system. Thus, blockade of both types of the mentioned receptors promotes the activation of both serotonin and adrenergic processes, i.e. provides a mechanism for the implementation of the antidepressant effect [7, 16, 26].

In addition, mirtazapine blocks 5-HT-2 and 5-HT-3 receptors, the activation of which is associated with unwanted side effects of TADs and SSRIs, including serotonin syndrome, agitation, anxiety, sexual dysfunction, dyspeptic disorders, headache and others [27]. At the same time, mirtazapine stimulates 5-HT-1 receptors, through which the actual antidepressant and anxiolytic effects of serotonin are realized [8, 12].

Thus, mirtazapine is characterized by a high degree of selectivity with respect to its effect on serotonin and adrenergic processes in the brain. It is important to emphasize that this selectivity manifests itself not only at the receptor, but also at the systemic level, promoting the activation of serotonin and adrenergic reactions, which are most significant from the point of view of pharmacotherapy of depression.

In addition, mirtazapine has the properties of a central blocker of histaminergic H1 receptors, exhibits anticholinergic properties to a small extent and has virtually no effect on dopaminergic processes [16, 24].

As a result, the clinical and pharmacological spectrum of action of mirtazapine is characterized by the following main features:

- the presence of pronounced thymoanaleptic and anxiolytic effects;

- the fastest possible onset of clinical effect (already in the 1st week of treatment);

- the presence of sedation and normalization of sleep.

In clinical practice, the use of mirtazapine has proven to be most effective for anxiety and depressive disorders, including in patients with severe agitation, anxiety, and sleep disorders [2, 6, 7, 18, 21]. It is especially important to emphasize the effectiveness of mirtazapine in severe depression, as well as in clinical forms resistant to conventional therapy (TAD and SSRIs) [5, 7, 16, 29]. In addition, given the low potential for drug-drug interaction of mirtazapine, in some cases with severe resistant depression, it is advisable to combine mirtazapine and venlafaxine as drugs that effectively complement each other from a pharmacological and clinical point of view [17].

One of the leading clinical advantages of mirtazapine is the early onset of thymoanaleptic and anxiolytic effects. Various studies of the effectiveness of mirtazapine compared with paroxetine, citalopram, and fluoxetine revealed significantly more pronounced effectiveness of mirtazapine in the 1-4 weeks of treatment, as well as higher rates of response to therapy [7, 16, 34]. When compared with amitriptyline, mirtazapine exhibits comparable efficacy, but patients treated with mirtazapine had fewer relapses (in a 2-year study) and greater persistence of remission than those treated with amitriptyline [33].

It is important to emphasize that the spectrum of clinical effects of mirtazapine includes a positive effect on symptoms of depression that are extremely difficult to correct with other antidepressants - anhedonia, psychomotor retardation, as well as cyclothymic disorders.

Thus, mirtazapine has proven to be an effective antidepressant both in the treatment of an acute depressive episode and as part of maintenance therapy. In addition to the anxiolytic profile of the drug, especially noteworthy is its normalizing effect on sleep.

Sleep disturbances in depression are one of the most typical diagnostic signs of this pathology, reflected in the DSM-IV [13] and observed in 80-90% of depressed patients. These include disturbances in falling asleep and waking up, as well as disorganization of sleep structure. In most cases, there is a clear correlation between the severity of the affective component and the severity of insomnia [9]. In this case, sleep disturbances can precede, accompany and/or seriously worsen the course of the pathological process, and also increase the likelihood of relapse [14].

Thus, a treatment strategy aimed at normalizing sleep structure in patients with depression can be considered not so much as symptomatic, but rather as pathogenetic therapy. In this regard, mirtazapine is one of the few antidepressants with proven effectiveness in correcting insomnia disorders in patients with depression [16].

Another relevant area of application of mirtazapine is geriatric practice. This drug is one of the best in terms of both effectiveness and tolerability in the elderly and senile [20, 28]. Considering that symptoms of depression such as concomitant anxiety, sleep disturbances, anhedonia and others are especially common in old age, as well as the fact that TAD drugs are not recommended for use in this age group [1], mirtazapine should be considered as the drug of choice in gerontopsychiatry for the treatment of all forms of depressive disorders.

Finally, a unique and very valuable property of mirtazapine is the possibility of correcting sexual disorders with its help (decreased libido, anorgasmia, accelerated ejaculation, etc.), which, on the one hand, are often one of the concomitant clinical manifestations of depression, and on the other hand, often develop as a complication of therapy with SSRI drugs [7, 11]. The possibility of safely switching therapy from SSRI drugs to mirtazapine, as well as the proven effectiveness of combination therapy (mirtazapine + SSRI) [30], allows in some cases not only to increase the effectiveness of treatment, but also to prevent the development of sexual dysfunction - one of the most common reasons for refusal to continue taking SSRIs.

Mirtazapine is one of the safest drugs in the antidepressant group. Unlike TAD, it is devoid of cardiotoxicity, does not have the ability to cause serotonin syndrome, and exhibits anticholinergic properties to a small extent (dry mouth, dyspepsia). The drug can sometimes cause increased sedation, dizziness, and drowsiness at the beginning of treatment, which, however, rarely reach clinically significant severity and usually disappear during further treatment. A more significant side effect of mirtazapine is considered to be increased appetite and weight gain, which, however, are also more often observed at the beginning of treatment and only in some cases can cause drug withdrawal [15, 25].

In direct comparative studies, mirtazapine proved to be a significantly safer antidepressant than amitriptyline, and compared to SSRI drugs, it was less likely to cause gastrointestinal disorders. Mirtazapine also had a beneficial effect on the sexual sphere [23, 25].

Thus, using the example of mirtazapine, one can verify the effectiveness of new generation antidepressants with a dual receptor mechanism of action (HaCCA) [3, 22, 32]. The possibility of using drugs that combine in their mechanism of action the effect on various neurotransmitter systems and the high selectivity of this effect allows:

- expand the possibilities of pharmacotherapy for various clinical forms of depressive disorders;

- ensure the earliest possible manifestation of the clinical effect;

- conduct effective and safe treatment for depressive disorders in various age groups;

- significantly reduce resistance rates during treatment with antidepressants.

In addition, mirtazapine treatment has been proven to be more cost-effective than amitriptyline and fluoxetine when assessing direct and indirect costs combined [10].

Among the mirtazapine drugs on the domestic pharmaceutical market, it is worth noting the appearance of the drug Mirtazapine Hexal (Germany), which combines a high level of quality in accordance with European standards and economic accessibility. Mirtazapine Hexal is available in the form of tablets of 15, 30 and 45 mg, which allows you to effectively combine different dosage regimens and schedules and titrate the dose depending on the characteristics of the clinical picture, treatment tolerance and concomitant pharmacotherapy in a particular patient.

Further expansion of experience with the use of mirtazapine may help optimize the pharmacotherapy of depressive disorders and improve the strategy and tactics of using new generations of antidepressants.

Literature 1. Burchinsky S.G. New approaches to optimizing pharmacotherapy of depression in the elderly and senile // Ukr. Newsletter of Psychoneurol. - 2006. - T.14, VIP. 1. - pp. 62-66. 2. Kolyutskaya E.V., Yastrebov D.V. The use of mirtazapine in the treatment of depression // Rus. honey. magazine - 1999. - T. 2, No. 2-3. — P. 50-52. 3. Morozova M.A. The effectiveness of mirtazapine therapy in patients with depression and affective disorders 4. Mosolov S.N. The current stage of development of psychopharmacotherapy // Ros. honey. magazine - 2002. - T. 10, No. 12-13. — P. 64-68. 5. Palamarchuk S.A. Remeron (mirtazapine) is a new generation antidepressant. Use in severe depression (literature review) // Tavrich. magazine psychiatrist - 2000. - T. 4, No. 1. - P. 51-54. 6. Petryuk P.T., Petryuk A.P. Clinical aspects of the use of mirtazapine (Remeron) in psychiatric practice // Mental Health. - 2005. - No. 3. - P. 54-60. 7. Remeron (mirtazapine) - a new generation antidepressant 8. Pharmacotherapy of depression: fourth generation of antidepressants 9. Abad VC, Guilleminault C. Sleep and psychiatry // Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. - 2005. - Vol. 7. - P. 291-303. 10. Brown MCJ, Nimmerrichter F., Guest JP Economic impact of using mitrazapine in the management of moderate and severe depression in France // Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. - 1998. - Vol. 8, Suppl. 2. - P. S150. 11. Clayton AH, Montejo AL Major depressive disorder, antidepressants and sexual dysfunction // J. Clin. Psychiat. - 2006. - Vol. 67, Suppl. 6. - P. 33-37. 12. Davis R., Wild MI Mitrazapine: a review of its pharmacology and therapeutic potential in the management of major depression // CNS Drugs. - 1996. - Vol. 5. - P. 389-402. 13. Fuchs E., Simon M., Schmelting B. Pharmacology of a new antidepressant: benefit of the implication of the melatonergic system // Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. - 2006. - Vol. 21, Suppl. 1. - P. S17-S20. 14. Gillin JC Are sleep disturbances risk factors for anxiety, depressive and addictive disorders? // Acta Psychiat. Scand. - 1998. - Vol. 98, Suppl. 393. - P. 39-43. 15. Gillman PK A systematic review of the serotonergic effects of mirtazapine in humans: implications for its dual action status // Hum. Psychopharmacol. - 2006. - Vol. 21. - P. 117-125. 16. Gorman JM Mirtazapine: clinical overview // J. Clin. Psychiat. - 1999. - Vol. 60, Suppl. 17. - P. 9-13. 17. Hannan N., Hamzah Z., Omeniyi A. et al. Venlafaxine — mirtazapine combination in the treatment of persistent depressive illness // J. Psychopharmacol. - 2006. - Vol. 19. - P. 43-49. 18. Holm KJ, Markham A. Mirtazapine: a review of its use in major depression // Adis. Drug Eval. - 1999. - Vol. 57. - P. 607-631. 19. Holmer AF Survey finds 103 medicines in clinical testing for mental disorders // New Med. Develop. Mental Illnesses. - 2000. - No. 6. - P. 1-16. 20. Hoyberg OJ, Maragakis B, Mullin J et al. A double-blind multicentre comparison of mirtazapine and amitriptiline in elderly depressed patients // Acta Psychiat. Scand. - 1996. - Vol. 93. - P. 184-190. 21. Lakatos L., Rihmer Z. 1×1 or 2×1? Another form of dual antidepressive mechanism of action // Neuropsychopharmacol. Hung. - 2005. - Vol. 7. - P. 118-124. 22. Millan MJ Serotonin 5-HT-2C-receptors as a target for the treatment of depressive and anxious states: focus on novel therapeutic strategies // Therapie. - 2005. - Vol. 60. - P. 441-460. 23. Montgomery SA Safety of mitrazapine: a review // Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. - 1995. - Vol. 10, Suppl. 4. - P. 37-45. 24. Nutt DJ Mirtazapne: pharmacology in relation to adverse effects // Acta Psychiat. Scand. - 1997. - Vol. 96, Suppl. 39. - P. 34-37. 25. Nutt DJ Tolerability and safety aspects of mirtazapine // Hum. Psychopharmacol. - 2002. - Vol. 17, Suppl. 1. - P. S37-41. 26. Pacher P., Kecskemeti V. Trends in the development of new antidepressants. Is there a light at the end of the tunnel? //Curr. Med. Chem. - 2004. - Vol. 11. - P. 925-943. 27. Pinder RM The pharmacologic rationale for the clinical use of antidepressants // J. Clin. Psychiat. - 1997. - Vol. 58. - P. 501-508. 28. Rabheru K. Special issues in the management of depression in older patients // Can. J. Psychiat. - 2004. - Vol. 49, Suppl. 1. - P. 41S-50S. 29. Richelson E. The pharmacologic rationale behind antidepressant efficacy in severe depression // J. Clin. Psychiat. - 1996. - Vol. 57. - P. 559-560. 30. Rojo JE, Ros S, Aguera L et al. Combined antidepressants: clinical experience // Acta Psychiat. Scand. - 2005. - Suppl. 428. - P. 25-31. 31. Schatzberg AF, Nemeroff CB Textbook of Psychopharmacology. —Washington: Amer. Psychiat. Press, 1998. - 598 p. 32. Stahl SM Are two antidepressant mechanisms better than one? // J. Clin. Psychiat. - 1997. - Vol. 58. - P. 339-340. 33. Stahl SM, Zivkov M., Reimitz PE et al. Meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, efficacy and safety studies of mirtazapine versus amitriptyline in major depression // Acta Psychiat. Scand. - 1997. - Vol. 96, Suppl. 391. - P. 22-30. 34. Wheatley DP, van Moffaert M, Timmerman L et al. Mirtazapine: efficacy and tolerability in comparison with fluoxetine in patients with moderate to severe major depressive disorder // J. Clin. Psychiat. - 1998. - Vol. 59. - P. 306-312.

Treatment regimen

◊ Dosage and dose selection

- For depression: 15-45 mg/day

- Initial dose – 15 mg in the evening; increase every 1-2 weeks until the effect is achieved; maximum – 45 mg/day

- Sedation will not increase with increasing dose

- Crushing the 15 mg tablet into two halves will increase sedation [1].

- For hot flashes: 7.5 mg-60 mg

- Insomnia/PTSD: 15-45 mg

- If anxiety, insomnia, agitation, or akathisia occur at the beginning of treatment or after interruption of treatment, the possibility of bipolar disorder should be considered and switched to a mood stabilizer or an atypical antipsychotic

◊ How quickly it works

- In patients with insomnia and anxiety, it may take immediate effect.

- Begins to act after 2-4 weeks

- If there is no effect after 6-8 weeks, you need to increase the dose or switch to another drug

- To prevent relapse, it can be taken for many years.

◊ Expected result

- Complete remission.

- After the symptoms of depression disappear, you should continue taking it for one year if this was the treatment of the first episode. If this is to treat a recurrent episode, treatment can be extended indefinitely.

- Use in the treatment of anxiety may be indefinite.

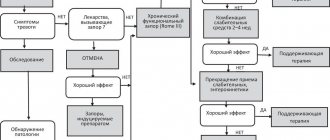

◊ If it doesn't work

- Change the dose, switch to another medicine or add an auxiliary drug;

- Connect psychotherapy;

- Review the diagnosis by identifying comorbid conditions;

- In patients with undiagnosed bipolar affective disorder, the effectiveness of treatment may be low, in which case it is necessary to switch to a mood stabilizer [1].

◊ How to stop taking it

It can be reduced gradually, but there is no need [1].

◊ Treatment combinations

- For fatigue, drowsiness, loss of concentration: modafinil [3].

- Use combinations with other antidepressants with caution because they may precipitate bipolar disorder and suicidal ideation.

- Combination with venlafaxine (“California Rocket Fuel”) is a strong combination, but watch for risk of bipolar disorder and suicidal ideation [1]

- Benzodiazepines

- For bipolar depression, psychotic depression, treatment-resistant depression, treatment-resistant anxiety disorder: mood stabilizers, atypical antipsychotics

- For anxiety disorder: gabapentin, tiagabine

Special patient groups

◊ Patients with kidney problems

With caution [1].

◊ Patients with liver disease

- Carefully;

- Lower doses are recommended [1].

◊ Patients with heart disease

- Carefully;

- Consider the risk of low blood pressure [1].

◊ Elderly patients

For some patients, it is better to stay at low doses [1].

◊ Children and teenagers

- Safety and benefit have not been proven

- It is necessary to regularly and personally check the patient's condition, especially in the first weeks of treatment.

- Inform adults about the risks.

◊ Pregnant women

- There have been no adequate studies in pregnant women [1].

- Not recommended for pregnant women, especially in the first trimester

- All risks should be weighed and compared

◊ Breastfeeding

- The medicine passes into breast milk.

- If the infant shows signs of irritation or sedation, stop feeding or taking mianserin

- However, treatment after childbirth may be necessary, so the risks should be weighed.

Side effects and other risks

◊ Mechanism of side effects

Most side effects occur immediately after starting treatment and go away over time, while the therapeutic effects increase over time. The action on the histamine receptor explains the sedation.

◊ Side effects

- Dry mouth, constipation, increased appetite

- Sedation, unusual dreams

- Low pressure

- Dangerous side effects: seizures, blood dyscrasia, mania

- Weight gain: very common

- Sedation: very common (worsens over time)

- Sexual dysfunction: no

◊ What to do about side effects

- Wait;

- Change drug [1].

◊ Long-term use

Safely

◊Addiction

Not expected.

◊ Overdose

- Rare cases of fatal overdoses have been associated with the use of mirtazapine along with other substances

- Sedation, disorientation, memory impairment.

results

- At week 12, Beck score was 18.0 (12.3) in the mirtazapine group and 19.7 (12.4) in the placebo group (adjusted mean difference, −1.83 (95% CI −3.92 to 0.27). ); P=0.09).

- At weeks 24 and 52, there were also no significant differences in depressive symptoms between the study groups (difference, −0.85 (95% CI −3.12 -1.43) at week 24 and 0.17 (95% CI −2 .13-2.46) at 52 weeks).

- Side effects were more common in the mirtazapine group. It was noteworthy that 46 patients from the main group stopped treatment due to adverse events, while only 9 in the placebo group.