- Symptoms of AF

- Pathogenesis and general clinical picture

- Causes of AF and risk factors

- Diagnostic methods

- AF treatment strategies

- Use of the drug Propanorm for AF

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a synonym for the more applicable term “Atrial Fibrillation” in the CIS countries.

Atrial fibrillation is the most common heart rhythm disorder. AF is not associated with a high risk of sudden death, so it is not classified as a fatal rhythm disorder, such as ventricular arrhythmias.

Atrial fibrillation

One of the most common types of supraventricular tachyarrhythmias is atrial fibrillation (AF). Fibrillation is a rapid, irregular contraction of the atria, with a frequency exceeding 350 beats per minute. The onset of AF is characterized by irregular contraction of the ventricles. AF accounts for more than 80% of all paroxysmal supraventricular tachyarrhythmias. Atrial fibrillation is possible in patients of all age categories, but in elderly patients the prevalence of the syndrome increases, which is associated with an increase in organic heart pathology.

Causes of development and risk factors

Cardiac pathology

- AMI (impaired conductivity and excitability of the myocardium).

- Arterial hypertension (LA and LV overload).

- Chronic heart failure (impaired myocardial structure, contractile function and conductivity).

- Cardiosclerosis (replacement of myocardial cells with connective tissue).

- Myocarditis (structural disorder due to inflammation of the myocardium).

- Rheumatic diseases with damage to the valves.

- SU dysfunction (tachy-brady syndrome).

Extracardiac pathology

- Diseases of the thyroid gland with manifestations of thyrotoxicosis.

- Drug or other intoxication.

- Overdose of digitalis preparations (cardiac glycosides) in the treatment of heart failure.

- Acute alcohol intoxication or chronic alcoholism.

- Uncontrolled treatment with diuretics.

- Overdose of sympathomimetics.

- Hypokalemia of any origin.

- Stress and psycho-emotional stress.

Age-related organic changes.

With age, the structure of the atrial myocardium undergoes changes. The development of small focal atrial cardiosclerosis can cause fibrillation in old age.

Prevention

Primary prevention of atrial fibrillation involves proper treatment of heart failure and arterial hypertension. Secondary prevention consists of:

- compliance with medical recommendations;

- conducting cardiac surgery;

- limiting mental and physical stress;

- giving up alcoholic drinks and smoking.

The patient must also:

- eat rationally;

- control body weight;

- monitor blood sugar levels;

- do not take medications uncontrollably;

- measure blood pressure daily;

- treat hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism.

This article is posted for educational purposes only and does not constitute scientific material or professional medical advice.

Classification of atrial fibrillation

According to the duration of clinical manifestations.

The following forms of AF are distinguished:

- Paroxysmal (paroxysmal).

Single episodes of AF lasting no more than 48 hours in the case of cardioversion, or up to 7 days in the case of spontaneous restoration of rhythm. - Persistent form.

Episodes of atrial fibrillation lasting more than 7 days without spontaneous recovery, or atrial fibrillation amenable to cardioversion (medical or electrical) after 48 hours or more. - Permanent form (chronic).

Continuous AF not amenable to cardioversion, if the physician and patient decide to abandon attempts to restore sinus rhythm.

By heart rate

- Tachysystolic.

Atrial fibrillation with a ventricular rate of more than 90–100 beats. per minute - Normosystolic.

The AV node allows the ventricles to contract at a rate of 60–100 beats/min. - Bradysystolic.

Heart rate with this form of fibrillation does not reach 60 beats/min.

Types of atrial fibrillation (AF)

The term “atrial fibrillation” can refer to the following two types of supraventricular tachyarrhythmia.

Fibrillation (atrial fibrillation).

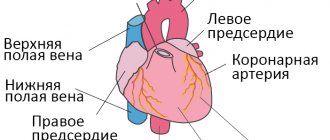

Normally, an electrical impulse arises in the sinus node (in the wall of the right atrium), spreads throughout the myocardium of the atria and ventricles, causing their successive contraction and ejection of blood. In AF, the electrical impulse travels chaotically, causing the atria to “flicker” as the myocardial fibers contract uncoordinatedly and very quickly. As a result of the chaotic transmission of excitation to the ventricles, they contract irregularly and, as a rule, not efficiently enough.

Atrial flutter.

In this case, contraction of myocardial fibers occurs at a slower pace (200–400 beats/min.). Unlike AF, with flutter the atria still contract. As a rule, due to the refractory period of the atrioventricular node, not every electrical impulse is transmitted to the ventricles, so they do not contract at such a rapid pace. However, as with fibrillation, with flutter the pumping function of the heart is disrupted, and the myocardium experiences additional stress.

Complications of atrial fibrillation

According to the latest data, patients with atrial fibrillation are at risk not only for the development of thromboembolic stroke, but also for myocardial infarction. The mechanisms of damage are as follows: with atrial fibrillation, full contraction of the atria is impossible, so the blood stagnates in them and blood clots form in the parietal space of the atria. If such a thrombus enters the aorta and smaller arteries with the blood flow, then thromboembolism occurs in the artery supplying any organ: the brain, heart, kidneys, intestines, lower extremities. The cessation of blood supply causes infarction (necrosis) of a section of this organ. A cerebral infarction is called an ischemic stroke. The most common complications are:

- Thromboembolism and stroke.

Most often, the target is the brain (through the straight carotid arteries, the thrombus quite easily “shoots” in this direction). According to statistics, every fifth patient with a stroke has a history of atrial fibrillation. - Chronic heart failure.

Atrial fibrillation and flutter can cause increased symptoms of circulatory failure, including attacks of cardiac asthma (acute left ventricular failure) and pulmonary edema. - Dilated cardiomyopathy.

The tachysystolic form of AF, when the frequency of ventricular contractions constantly exceeds 90 beats, quickly leads to pathological expansion of all cardiac cavities. - Cardiogenic shock and cardiac arrest

. In rare cases, an attack of atrial fibrillation or flutter with severe hemodynamic disturbances can lead to arrhythmogenic shock, a life-threatening condition.

Diet

With atrial fibrillation, the patient should eat foods rich in vitamins, microelements and substances that can break down fats. This means:

- garlic, onion;

- citrus;

- honey;

- cranberry, viburnum;

- cashews, walnuts, peanuts, almonds;

- dried fruits;

- dairy products;

- sprouted wheat grains;

- vegetable oils.

The following should be excluded from the diet:

- chocolate, coffee;

- alcohol;

- fatty meat, lard;

- flour dishes;

- smoked meats;

- canned food;

- rich meat broths.

Apple cider vinegar helps prevent blood clots from forming. 2 tsp. You need to dilute it in a glass of warm water and add a spoonful of honey. Drink half an hour before meals. The preventive course is 3 weeks.

Drug therapy

The following areas of drug therapy for atrial fibrillation are distinguished: cardioversion (restoration of normal sinus rhythm), prevention of repeated paroxysms (episodes) of supraventricular arrhythmias, control of the normal frequency of contractions of the ventricles of the heart. Another important goal of drug treatment for MA is the prevention of complications - various thromboembolisms. Drug therapy is carried out in four directions.

Treatment with antiarrhythmics.

It is used if a decision has been made to attempt drug cardioversion (restoring the rhythm with the help of drugs).

The drugs of choice are propafenone, amiodarone.

Propaphenone

is one of the most effective and safe drugs used to treat supraventricular and ventricular heart rhythm disorders. The action of propafenone begins 1 hour after oral administration, the maximum concentration in the blood plasma is reached after 2–3 hours and lasts 8–12 hours.

Heart rate control.

If it is impossible to restore the normal rhythm, it is necessary to bring the atrial fibrillation back to normal form. For this purpose, beta-blockers, non-dihydropyridine calcium antagonists (verapamil group), cardiac glycosides, etc. are used.

Beta blockers

. Drugs of choice for controlling heart function (frequency and strength of contractions) and blood pressure. The group blocks beta-adrenergic receptors in the myocardium, causing a pronounced antiarrhythmic (heart rate reduction) as well as hypotensive (blood pressure reduction) effect. Beta blockers have been shown to statistically increase life expectancy in heart failure. Contraindications for use include bronchial asthma (since blocking beta 2 receptors in the bronchi causes bronchospasm).

Anticoagulant therapy.

To reduce the risk of thrombosis in persistent and chronic forms of AF, blood thinning drugs must be prescribed. Anticoagulants of direct (heparin, fraxiparin, fondaparinux, etc.) and indirect (warfarin) action are prescribed. There are regimens for taking indirect (warfarin) and so-called new anticoagulants - antagonists of blood clotting factors (Pradaxa, Xarelto). Treatment with warfarin is accompanied by mandatory monitoring of coagulation parameters and, if necessary, careful adjustment of the drug dosage.

Metabolic therapy.

Metabolic drugs include drugs that improve nutrition and metabolic processes in the heart muscle. These drugs purport to have a cardioprotective effect, protecting the myocardium from the effects of ischemia. Metabolic therapy for MA is considered an additional and optional treatment. According to recent data, the effectiveness of many drugs is comparable to placebo. Such medicines include:

- ATP (adenosine triphosphate);

- K and Mg ions;

- cocarboxylase;

- riboxin;

- mildronate;

- preductal;

- mexico.

Diagnosis and treatment of any type of arrhythmia requires considerable clinical experience, and in many cases, high-tech hardware. In case of atrial fibrillation and flutter, the main task of the doctor is, if possible, to eliminate the cause that led to the development of the pathology, preserve heart function and prevent complications.

ATRIAL FIBRILLATION AND FLUTTER

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common tachyarrhythmia, the incidence of which increases significantly with age. According to the Framingham study, it is diagnosed in 2-4% of the general population of people over 65 years of age, while less than 1% are diagnosed under 60 years of age. At least a third of those hospitalized due to cardiac arrhythmias are patients with AF, and in older age groups, according to our data, their number reaches 70%. Population studies indicate that atrial flutter (AFL) occurs significantly less frequently than atrial fibrillation: no more than 0.09% in the general population, and in people over 80 years of age – 0.7%.

The priority of electrocardiographic diagnosis of AF in humans is associated with the names of two European scientists - C. Rothberger and H. Winterberg, who in 1909 described its characteristic ECG signs. At the same time, T. Lewis in 1920 was the first to suggest that the cause of this arrhythmia could be the circulation of an excitation wave in the atria. Atrial flutter and ECG criteria for differential diagnosis with AF were first described in 1911 by W. Jolly and W. Ritchie.

ECG diagnostics

Electrocardiographic diagnosis of atrial fibrillation and flutter, as a rule, rarely causes difficulties. ECG signs of AF are the absence of P waves, instead of which small, irregular ascilations of varying amplitude and shape, called F waves (their frequency from 350 to 600 per minute) and RR intervals of varying duration are recorded.

The rate of ventricular responses with normal atrioventricular (AV) conduction and the absence of additional atrioventricular conduction pathways ranges from 100 to 160 per minute.

Unlike atrial fibrillation, in which there is no effective contraction, AFL is accompanied by regular and coordinated excitation of the atrial myocardium and their active systole. Electrocardiographically, two types of AFL are distinguished. Type 1

(“typical” or “improved” AV conduction until the development of 1:1 AFL with a very high ventricular rate and corresponding negative hemodynamic manifestations.

Clinic

Most patients with atrial fibrillation and flutter are diagnosed with cardiovascular disease. Thus, atrial fibrillation is often recorded in hypertension and coronary artery disease and in 40-50% of patients with mitral stenosis undergoing surgery. In addition, AF develops in 10-20% of patients with thyrotoxicosis, in 20-50% of adult patients with atrial septal defect, in 25% of patients with dilated and 10% with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. It occurs in 25-30% of patients after coronary artery bypass surgery and in 40% of cases during surgery on the heart valves. The cause of AF may be alcoholic heart disease (“holiday heart”). Less commonly, AF occurs in amyloidosis and sarcoidosis of the heart, hypothyroidism, ventricular septal defect, and chronic lung diseases.

In 5-11% of patients, no signs of disease of the cardiovascular system, lungs or endocrine pathology can be detected. In these cases, the term “idiopathic” AF (“isolated” atrial fibrillation – lone atrial fibrillation) is used. Among young patients, idiopathic AF accounts for 20 to 45% of all cases of paroxysmal and persistent AF. There are vagal, adrenergic and mixed (unspecified) idiopathic AF. There is evidence of a family predisposition to the development of AF, and some authors believe that the cause of arrhythmia in these patients may be structural changes in the atrial myocardium as a consequence of a history of asymptomatic myocarditis.

It is necessary to highlight atrial fibrillation and flutter in acute diseases and conditions: myocardial infarction, acute pericarditis, pneumonia, chest trauma, acute alcohol intoxication, intoxication with cardiac glycosides, taking sympathomimetics, etc. Attacks of AF/AFL in these patients, as a rule, do not recur after resolution of the underlying disease or cessation of intoxication and, therefore, often do not require long-term preventive antiarrhythmic therapy.

Atrial fibrillation and flutter worsen hemodynamics, aggravate the course of the underlying disease and lead to an increase in mortality by 1.5-2 times in patients with organic heart disease. Non-valvular (non-rheumatic) AF increases the risk of ischemic stroke by 2-7 times compared with the control group (patients without AF), and in rheumatic mitral disease with chronic AF it increases by 15-17 times. The incidence of ischemic stroke in non-rheumatic atrial fibrillation averages about 5% per year. Atrial fibrillation is the cause of stroke in 7-31% of patients over 60 years of age. The risk of stroke is low in patients with idiopathic AF younger than 60 years (1% per year) and slightly higher (2% per year) at the age of 60-70 years (Mayo clinic study, 1980). The risk of thromboembolic complications also increases significantly with atrial flutter.

Classification

Traditionally, atrial fibrillation and flutter, like other tachyarrhythmias, were divided into paroxysmal and chronic. However, in 2001, experts from the American College of Cardiologists and the Heart Association and the European Society of Cardiology (ACC/ANA/ESC) proposed a different classification of AF (adopted by the All-Russian Scientific Society of Cardiology in 2005):

1. First identified

.

2. Paroxysmal

: duration up to 7 days, self-limiting.

3. Persistent

: duration usually more than 7 days, does not stop on its own.

4. Constant

: Cardioversion (medical or electrical) is ineffective or has not been performed.

We can agree with the opinion of M.M. Gallagher (1997) that in some cases it will be necessary to distinguish a mixed form of AF (paroxysmal-persistent), when some episodes of atrial fibrillation resolve on their own, while others require cardioversion.

Based on the frequency of ventricular contractions, brady-, normo-, and tachysystolic forms of AF/AFL are distinguished (the frequency of ventricular contractions per 1 minute, respectively, is less than 60, from 60 to 99, 100 or more).

TREATMENT

The main directions in the treatment of atrial fibrillation and flutter are:

1. Establishing the cause of AF and AFL and influencing it (surgical treatment of mitral valve disease, treatment of hyperthyroidism, limiting or stopping alcohol intake, eliminating an overdose of cardiac glycosides, sympathomimetics, etc.).

2. Prevention of thromboembolic complications.

3. Heart rate control, stopping and preventing relapses of arrhythmia. Table 1 presents the classification of antiarrhythmic drugs by E. Vaughan Williams.

Table 1. Classification of antiarrhythmic drugs E.Vaughan Williams*

| Class I Sodium channel blockers: | |

| IA disopyramide, procainamide, quinidine; | |

| IV lidocaine, mexiletine, phenytoin (diphenin); | |

| IC flecainide, moricizine (ethmosin), propafenone. | |

| Class II Beta-adrenergic receptor blockers. | |

| Class III Drugs that increase the duration of the action potential: amiodarone, sotalol, dofetilide, ibutilide, etc. | |

| Class IV Calcium channel blockers: verapamil, diltiazem. | |

* Domestic antiarrhythmics etatsizin and allapinin belong to class IC, and nibentan – to class III.

RELIEF OF PAROXYSMS

It is known that 50-60% of recently developed (less than 48 hours) paroxysms of AF cease on their own. Spontaneous restoration of sinus rhythm occurs much less frequently with prolonged (more than 7 days) atrial fibrillation, and pharmacological cardioversion with most antiarrhythmics during these periods becomes significantly less effective. The algorithm for emergency treatment of AF/AFL is presented in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1. Relief of paroxysm of atrial fibrillation.

TPEchoCG – transesophageal echocardiography; EIT – electric pulse therapy; * - with a high risk of thromboembolism (history of thromboembolism, severe heart failure, mitral stenosis, etc.), TPEchoCG or long-term anticoagulant therapy is probably necessary before cardioversion; ** - use only in specialized cardiology departments; *** — electrical cardioversion is the main method of stopping prolonged attacks of AF/AFL (more than 48 hours) regardless of the state of LV myocardial contractility; **** - with a high risk of rhythm disruption and the development of thromboembolism, long-term antithrombotic therapy.

It is not advisable to dock

:

1. Short-term, well-tolerated attacks of atrial fibrillation and flutter.

2. Paroxysms of AF/AFL (in the absence of urgent indications) in patients with a high risk of recurrence: sick sinus syndrome, especially in the absence of an implanted pacemaker; untreated hyperthyroidism; significant enlargement of the heart chambers, refractory to preventive antiarrhythmic therapy, etc. In these patients, heart rate is reduced and thromboembolism is prevented (indirect anticoagulants or aspirin).

When a paroxysm of tachyarrhythmia leads to a critical deterioration of the patient’s condition, immediate EIT

. Transthoracic electrical cardioversion of atrial fibrillation, which must be synchronized with the heart's own electrical activity (in parallel with the R wave on the ECG), begins with a 200 J shock (for biphasic current, the discharge energy is less). When the first shock is ineffective, shocks of higher power are applied - 300, 360 J. TP is often stopped with a low energy discharge - 100 J. If the first attempt at EIT was not successful, it is recommended to change the position of the electrodes (antero-posterior to antero-lateral or vice versa), administer an antiarrhythmic before repeated cardioversion (for this purpose, intravenous administration of ibutilide or nibentan is suggested), and in specialized departments use transvenous endocardial electrical cardioversion.

If the duration of paroxysm of fibrillation or atrial flutter is more than 2 days

it is necessary to prescribe indirect anticoagulants (maintaining INR at 2.0-3.0) for 3-4 weeks before and after electrical or drug cardioversion. When the duration of AF/AFL is unknown, the use of indirect anticoagulants before and after cardioversion is also necessary. Currently, coumarin derivatives (warfarin) are mainly used.

Indirect anticoagulants before cardioversion are not used for a long time if intracardiac thrombi are excluded using transesophageal echocardiography (in 95% of cases they are localized in the left atrial appendage). This is the so-called early cardioversion

: intravenous administration of unfractionated heparin (first infusion of 60 units/kg, but not more than 4000 units, then drip at a rate that ensures an increase in aPTT of 1.5-2.0 compared to the control value) and/or short-term use of an indirect anticoagulant (bringing the INR to 2.0-3.0) before cardioversion and continuing to take it for 3-4 weeks after restoration of sinus rhythm. Thus, transesophageal echocardiography saves time before cardioversion, which is especially important in patients with unstable hemodynamics.

If the duration of the arrhythmia is even more than 48 hours, in case of emergency EIT in patients with complicated AF/AFL, it is not postponed until therapeutic hypocoagulation is achieved. Unfractionated heparin is injected intravenously and then administered intravenously under APTT control. After restoration of sinus rhythm, therapy with oral anticoagulants (INR 2.0-3.0) continues for 3-4 weeks.

Atrial flutter is more difficult to slow down and stop with antiarrhythmics

Therefore, electrical pulse therapy and cardiac pacing are more often used. It has been proven that the use of a number of class I and III antiarrhythmics (procainamide, disopyramide, propafenone, ibutilide) before cardiac stimulation, “facilitating the penetration” of the impulse into the re-entry circuit, increases its effectiveness and reduces the risk of provoking AF.

If there are no indications for emergency EIT, one of the main goals for tachysystolic fibrillation or atrial flutter is to reduce the heart rate and only then, if the paroxysm does not stop on its own, is it stopped. As mentioned above, before drug cardioversion of AF/AFL (especially atrial flutter) occurring at a high heart rate, antiarrhythmic drugs of IA and IC classes, conduction block in the AV node is required, because they can significantly increase the frequency of ventricular contractions.

Heart rate control (decrease to 70-90 per minute) is carried out by intravenous administration of verapamil, diltiazem, beta-blockers, cardiac glycosides (preference is given to digoxin), amiodarone, and in less acute situations, oral use of verapamil, diltiazem, beta-blockers can be recommended. adrenergic blockers:

1. Verapamil

5-10 mg (0.075-0.15 mg/kg) IV over 2 minutes or orally 120-360 mg/day.

2. Diltiazem

20 mg (0.25 mg/kg) IV over 2 minutes (continuous infusion 5-15 mg/hour) or orally 180-360 mg/day.

3. Metoprolol

5.0 mg IV over 2 to 3 minutes (up to 3 5.0 mg doses may be given 5 minutes apart) or 25 to 100 mg orally twice daily.

4. Propranolol

5-10 mg (up to 0.15 mg/kg) IV over 5 minutes or orally 80-240 mg/day.

5. Esmolol

0.5 mg/kg IV over 1 minute (continuous infusion 0.05-0.2 mg/kg/min).

6. Digoxin

0.25-0.5 mg IV, then for rapid saturation, 0.25 mg IV can be administered every 4 hours up to a total dose of no more than 1.5 mg. Maintenance dose 0.125-0.25 mg.

7. Amiodarone

5-7 mg/kg IV over 30-60 minutes (15 mg/min), then IV infusion up to 1.2-1.8 g/day (50 mg/hour). Oral: 800 mg/day. – 1 week, 600 mg/day. – 1 week, 400 mg/day. – 4-6 weeks, then a maintenance dose of 100-200 mg/day.

Verapamil, diltiazem and beta blockers are first line drugs

for emergency intravenous reduction of heart rate, since these antiarrhythmics are highly effective and quickly (within 5-10 minutes) manifest their effect. With IV administration of digoxin, a sustained slowdown in ventricular rate is achieved much later (after 2-4 hours). However, if the contractile function of the LV is reduced (congestive heart failure, cardiac glycosides or amiodarone. In patients with a high risk of systemic embolism (AF/AFL lasting more than 2 days), amiodarone to reduce the heart rate is a reserve drug: it is possible to restore sinus rhythm and, therefore, the appearance of “normalization” thromboembolism.

Table 2 presents the main antiarrhythmics used for pharmacological cardioversion of AF/AFL.

A number of international recommendations (ACC/AHA/ESC, 2000, 2001, 2003) note that relief of paroxysmal AF/AFL in patients with heart failure or EF less than 40% should be carried out with amiodarone.

Other antiarrhythmics should be used with caution or not be used due to the relatively high risk of developing arrhythmogenic effects and negative effects on hemodynamics. A meta-analysis of the results of placebo-controlled studies on cardioversion of AF with amiodarone showed late relief of arrhythmia paroxysms: a significant difference in effectiveness between amiodarone and placebo was noted no earlier than 6-8 hours after their intravenous use.

Taking this into account, after intravenous administration of a “loading” dose of amiodarone (5 mg/kg over 30-40 minutes), it is advisable to then continue its intravenous infusion (300-600 mg) for 6-12 hours (administration rate 50 mg/day). hour).

If the arrhythmia does not stop, the IV administration of amiodarone can be prolonged or the issue of performing EIT can be decided. The reduction in ventricular rate with intravenous use of amiodarone occurs quite quickly (blockade of beta-adrenergic receptors and calcium channels), which makes AF/AFL easier to tolerate.

Table 2. Antiarrhythmic drugs for intravenous relief of atrial fibrillation and flutter

| A drug | Dose and route of administration | Main side effects |

| Amiodarone | IV administration of 5-7 mg/kg over 30-60 minutes. (15 mg/min.), then continued intravenous administration of 1.2-1.8 g/day. (50 mg/hour) | Hypotension, bradycardia, QT prolongation, torsade de pointes (rare) |

| Ibutilide* | IV administration 1 mg per 10 min. If necessary, repeated intravenous administration of 1 mg | QT interval prolongation, torsade de pointes (TdP) |

| Nibentan * | IV 0.125 mg/kg. Repeated administration is possible after 15 minutes. | QT interval prolongation, torsade de pointes (TdP) |

| Novocainamide* [] | IV infusion 1.0-1.5 g (up to 15-17 mg/kg) at a rate 30-50 mg/min. | Hypotension, prolongation of the QT interval, tachycardia “pirouette”, “improvement” of AV conduction with increasing heart rate |

| Propaphenone*¨ | IV administration 1.5-2.0 mg/kg over 10-20 minutes. | Hypotension, QRS widening, atrial flutter with rapid AV conduction |

| Flecainide*¨ | IV administration 1.5-3.0 mg/kg over 10-20 minutes. | Hypotension, QRS widening, atrial flutter with rapid AV conduction |

* - Heart failure or EF less than 40% - use with caution or not use; [] – less effective than other listed drugs; ¨

- chronic ischemic heart disease - use with caution or not use (unstable angina, myocardial infarction - contraindicated)

Ibutilide is highly effective in the pharmacological cardioversion of fibrillation and especially atrial flutter.

and

nibentan

. The effectiveness of nibentan in stopping paroxysmal AF and AFL is more than 80%, and arrhythmogenic effects are 2.9% of VT “torsades de pointes” and 7.8% of bradycardia (L. Rosenshtrauch et al., 2003). Nibentan and ibutilide should be used only in specialized departments under electrocardiographic control (contraindicated in patients with heart failure, prolonged QT interval and CVS).

Effective antiarrhythmics that are recommended for clinical use for the purpose of conversion of atrial fibrillation are class IC drugs propafenone and flecainide.

.

They are effective when administered intravenously and orally. For oral relief, take a single dose of 600 mg

of propafenone or

300 mg

of flecainide. Sinus rhythm in patients with AF is restored 2-6 hours after oral administration. According to our placebo-controlled study, the effectiveness of propafenone in atrial fibrillation (single oral dose of 600 mg, observed for 8 hours) is approximately 80%. However, several randomized, controlled studies emphasize the limited ability of intravenously administered propafenone to convert LT (no more than 40%). Our observations also indicate a rather low effectiveness of propafenone in the oral treatment of TP. The use of class IC antiarrhythmics is contraindicated in patients with acute myocardial ischemia (unstable angina, MI).

The effectiveness of novocainamide in stopping AF (should be administered intravenously, not as a stream, but as a drip, at a rate of 30-50 mg/min) is higher than placebo, but less than that of all of the above antiarrhythmic drugs.

When a paroxysm of atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter develops in a patient with sick sinus syndrome

(bradycardia-tachycardia syndrome) without an implanted pacemaker (pacemaker), then in the absence of emergency indications, it is necessary to monitor it until the attack spontaneously stops, since the use of antiarrhythmics increases the risk of severe bradycardia after the end of the arrhythmia.

To relieve paroxysms of AF/AFL in patients without a pacemaker, class IA antiarrhythmics (disopyramide, procainamide, quinidine) are used, the anticholinergic effect of which reduces the risk of developing asystole after restoration of sinus rhythm. However, electropulse therapy is a safer method of stopping them than the use of antiarrhythmic drugs. Conversion of tachyarrhythmia, even with the help of class IA antiarrhythmics or EIT, can be complicated by asystole or the appearance of a replacement rhythm with a low heart rate. In this regard, restoration of sinus rhythm is recommended to be carried out in a hospital under the cover of temporary cardiac pacing. With an implanted pacemaker, relief of AF and AFL is carried out according to general principles.

In patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome (WPU)

the frequency of ventricular contractions during AF and AFL, as a rule, is higher than in patients without ventricular preexcitation syndrome, and reaches 220-250 per minute or more, and the ECG shows tachycardia with an irregular rhythm and wide QRS complexes.

The use of verapamil, diltiazem, and cardiac glycosides is contraindicated in VPU syndrome, since they, by reducing the refractoriness of the Kent bundle, can increase heart rate and even cause ventricular fibrillation. AF/AFL is treated with drugs that impair conduction along the accessory atrioventricular conduction pathway. International recommendations for the treatment of patients with AF (ACC/AHA/ESC, 2001) suggest that for this purpose, primarily intravenous administration of procainamide or ibutilide (nibentan)

. When AF or AFL in VPU syndrome is complicated by severe hemodynamic disorders, emergency electrical cardioversion is performed.

Development of paroxysm of atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter in a patient with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM)

leads to the appearance or worsening of symptoms of congestive heart failure. Therefore, they usually need restoration of sinus rhythm. Taking into account the significant increase in the risk of arrhythmogenic action (including the development of tachycardia of the “pirouette” type) of a number of antiarrhythmic drugs in patients with significant myocardial hypertrophy, it is likely that it is advisable to use amiodarone or EIT to stop AF/AFL in HCM.

(The ending follows.)

PREVENTION OF THROMBOEMBOLIC COMPLICATIONS AND RECURRENCES

Risk stratification of thromboembolic complications, prevention of ischemic stroke and systemic embolism are one of the most important tasks in the treatment of atrial fibrillation and flutter.

A meta-analysis of eleven studies on the primary and secondary prevention of strokes in AF showed that indirect anticoagulants reduce the risk of their development by an average of 61%, and aspirin by a little more than 20%. It should be noted that the use of aspirin only in a fairly high dose (325 mg/day) showed the possibility of a statistically significant reduction in the incidence of ischemic stroke and other systemic embolisms.

Therefore, patients with AF who are at high risk for thromboembolic complications (heart failure, EF 35% or less, arterial hypertension, ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack in history, mitral stenosis, etc.) should be prescribed indirect anticoagulants (maintenance of INR, on average, at the level of 2.0-3.0). For patients with non-valvular (non-rheumatic) atrial fibrillation who are not at high risk, continuous use of aspirin (325 mg/day) is advisable. Patients under 60 years of age with idiopathic AF, in whom the risk of thromboembolic complications is very low, do not need prophylactic therapy. Antithrombotic therapy in patients with AFL is based on taking into account the same risk factors as in AF, because the risk of thromboembolic complications in AFL is higher than in sinus rhythm, but somewhat less than in AF.

Coumarin derivatives (warfarin, etc.) are preferred over another group of indirect anticoagulants - indanedione derivatives (phenylin) due to their good bioavailability and the stability of the achieved hypocoagulation.

ACC/AHA/ESC (2001) experts offer the following specific recommendations for antithrombotic prophylaxis in patients with atrial fibrillation:

1. Age less than 60 years (no heart disease - lone AF): aspirin 325 mg/day.

or without treatment.

2. Age less than 60 years (heart disease, but no risk factors such as heart failure, EF 35% or less, arterial hypertension): aspirin 325 mg/day.

3. Age 60 years or more (diabetes mellitus or coronary artery disease): oral anticoagulants (INR 2.0-3.0).

4. Age 75 years or more (especially women): oral anticoagulants (INR up to 2.0)

5. Heart failure: oral anticoagulants

(INR 2.0-3.0).

6. LVEF 35% or less: oral anticoagulants (INR 2.0-3.0).7. Thyrotoxicosis: oral anticoagulants (INR 2.0-3.0).

8. Arterial hypertension: oral anticoagulants (INR 2.0-3.0).

A necessary condition is adequate blood pressure control.

9. Rheumatic heart defects (mitral stenosis): oral anticoagulants (INR 2.5-3.5 or more).

10. Artificial heart valves :

oral anticoagulants (INR 2.5-3.5 or more).

11. History of thromboembolism: oral anticoagulants (INR 2.5-3.5 or more).12. Presence of a thrombus in the atrium according to TPEchoCG: oral anticoagulants (INR 2.5-3.5 or more).

Evidence has recently been provided of the fairly high efficacy of the direct thrombin inhibitor ximelagatran.

(no need to monitor coagulation parameters) in the prevention of ischemic stroke in patients with AF (SPORTIF III and V studies, 2005)

In patients with asymptomatic recurrent paroxysmal and persistent AF/AFL, in most cases there is no need to use antiarrhythmic drugs. They carry out prevention of thromboembolic complications and heart rate control. If clinical symptoms are severe, anti-relapse and relief therapy is required, combined with heart rate control and antithrombotic treatment.

For rare, mild but prolonged attacks of AF/AFL, the use of oral relief therapy is justified. At the same time, frequent hemodynamically significant and rare paroxysms with severe clinical symptoms require preventive antiarrhythmic therapy. For frequent attacks, the effectiveness of antiarrhythmics or their combinations is assessed clinically; for rare attacks, transesophageal cardiac pacing ( TEPS)

) after 3-5 days of taking the drug, and when prescribing amiodarone after saturation with it.

To prevent relapses of AF/AFL in patients without organic heart disease and coronary artery disease, antiarrhythmic drugs of classes IA, IC and III

.

In patients with asymptomatic LV dysfunction or symptomatic chronic heart failure (CHF), therapy with class I

is contraindicated due to the risk of worsening life prognosis. It is not advisable to use IC class drugs for ischemic heart disease (especially during its exacerbation).

Table 3

Antiarrhythmics used to prevent paroxysms of atrial fibrillation and treperation.

| quinidine - 750-1500 mg/day. disopyramide - 400-800 mg/day. propafenone - 450-900 mg/day. allapinin - 75-150 mg/day. | etacizin - 150-200 mg/day. flecainide - 200-300 mg/day. amiodarone (maintenance dose) - 100-200 mg/day. sotalol - 160-320 mg/day. dofetilide - 500-1000 mcg/day. |

When monitoring antiarrhythmic therapy, it is necessary to take into account concomitant diseases and other conditions that affect its effectiveness and safety. The arrhythmogenic effect of antiarrhythmic drugs is less likely to occur in patients with idiopathic AF/AFL, while at the same time with severe organic heart damage, electrolyte disturbances, hypoxia, etc. they occur much more often. Treatment with antiarrhythmics requires monitoring the width of the QRS complex (especially when class IC antiarrhythmics are used) and the duration of the QT interval (therapy with class IA and III antiarrhythmics). The width of the QRS complex should not increase by more than 50% of the initial level, and the corrected QT interval should not exceed 500 ms.

Amiodarone has the greatest preventive antiarrhythmic effect

.

A meta-analysis of published placebo-controlled studies showed that low maintenance doses of amiodarone ( less than 400 mg/day

) did not cause an increase in lung and liver damage compared with placebo (VRVorperian et al., 1997). Some clinical studies have shown a higher preventive effectiveness of class IC drugs (propafenone, flecainide) compared to class IA antiarrhythmics quinidine and disopyramide. According to our data, the effectiveness of propafenone is 65%. In recent years, a number of reports have appeared on the advisability of using ACE inhibitors in complex preventive antiarrhythmic therapy for AF. Continuation of these studies will show the practical significance of these assumptions.

SELECTION OF A DRUG FOR PREVENTIVE ANTIARRYTHMIC THERAPY

We can agree with the opinion expressed in the international recommendations for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation (2001) that anti-relapse therapy in patients without heart pathology or with minimal structural changes should begin with class IC antiarrhythmics ( propafenone, flecainide

), let's add to them domestic drugs of the same class (

allapinin and etacizin

), and

sotalol

, since they are quite effective and devoid of pronounced extracardiac side effects.

If these antiarrhythmics do not prevent relapses of AF/AFL or their use is accompanied by side effects, it is necessary to proceed to the prescription of second-line antiarrhythmic drugs ( amiodarone, dofetilide

), and then, if necessary, third-line drugs of class IA (

disopyramide, quinidine

) or use non-pharmacological treatment methods .

Coronary heart disease (especially in the presence of post-infarction cardiosclerosis) and heart failure increase the risk of manifestation of the arrhythmogenic properties of antiarrhythmic drugs. Therefore, treatment of atrial fibrillation and flutter in patients with congestive heart failure is usually limited to the use of amiodarone and dofetilide.

. The high efficacy and safety of amiodarone in heart failure and coronary artery disease (including myocardial infarction) has been proven for a long time, and dofetilide - in the placebo-controlled studies DIAMOND CHF and DIAMOND MI conducted in 2000.

In patients with coronary heart disease, the recommended sequence of prescribing antiarrhythmics is as follows: 1) sotalol

, 2)

amiodarone, dofetilide

;

3) disopyramide, quinidine

. Sotalol is considered by ACC/AHA/ECC experts as a first-line drug for ischemic heart disease due to the fact that it combines the properties of a beta-blocker (certainly useful for this disease) and an effective class III antiarrhythmic. Arrhythmogenic effects (bradycardia and ventricular tachycardia, including the “pirouette” type), which manifest themselves mainly at the beginning of treatment with sotalol, require special attention. Daily ECG recording is required (monitoring the duration of the QT, PQ intervals, ventricular rate, and the appearance of ventricular ectopy) in the first 4 days of taking the drug.

Arterial hypertension, leading to hypertrophy of the left ventricular myocardium, increases the risk of developing polymorphic ventricular tachycardia “torsades de pointes”. In this regard, antiarrhythmic drugs that do not significantly affect the duration of repolarization and the QT interval ( IC class

), as well as

amiodarone

, although it prolongs it, but extremely rarely causes ventricular tachycardia, is preferred in preventing relapses of AF/AFL in patients with high blood pressure.

Thus, the algorithm for pharmacotherapy of this rhythm disorder in arterial hypertension appears to be as follows: 1) LV myocardial hypertrophy of 1.4 cm or more - use only amiodarone

;

2) there is no LV myocardial hypertrophy or it is less than 1.4 cm - start treatment with propafenone, flecainide

(bear in mind the possibility of using domestic class IC antiarrhythmics

allapinin and etacizin

), and if they are ineffective, use

amiodarone, dofetilide, sotalol

.

At the next stage of treatment (ineffectiveness or side effects of the above drugs), disopyramide

or

quinidine

.

Verapamil, diltiazem and cardiac glycosides should not be used for anti-relapse therapy in patients with VPU syndrome, because they may worsen the course of the arrhythmia.

In patients with sick sinus syndrome

and paroxysms of AF/AFL, the indications for pacemaker implantation have been expanded. They need permanent pacing both for the treatment of symptomatic bradyarrhythmia and for the safe administration of antiarrhythmic therapy.

For HCM

To prevent paroxysms of tachyarrhythmia, amiodarone is prescribed, and to slow down the frequency of ventricular contractions, beta blockers or calcium antagonists (verapamil, diltiazem).

It is quite likely that changes will be made to the above recommendations for the prevention of relapses of paroxysmal and persistent AF if new data from controlled studies on the effectiveness and safety of antiarrhythmic drugs in patients with various diseases of the cardiovascular system become available, since at present they are clearly insufficient.

If there is no effect from monotherapy, combinations of antiarrhythmic drugs are used, starting with half doses. The most studied combinations of beta blockers, verapamil with amiodarone and class IC drugs. An addition, and in some cases an alternative to preventive therapy (as discussed above), may be the prescription of drugs that worsen AV conduction and reduce the frequency of ventricular contractions during paroxysms of AF/AFL. The effectiveness and safety of this treatment strategy for AF/AFL was proven in the AFFIRM study (2002).

The use of drugs that impair conduction in the AV junction is also justified in the absence of effect from preventive antiarrhythmic therapy. When using them, it is necessary to ensure that the heart rate during tachyarrhythmia at rest is from 60 to 80 per minute, and with moderate physical activity - no more than 100-110 per minute. Cardiac glycosides are little effective for controlling heart rate in patients leading an active lifestyle, since in them the primary mechanism for reducing the frequency of ventricular contractions is an increase in parasympathetic tone. Therefore, cardiac glycosides are the drugs of choice, obviously, only in two clinical situations: with heart failure and in patients with little physical activity. In all other cases, preference is given to calcium antagonists (verapamil, diltiazem) or beta-blockers. To reduce heart rate, you can use combinations of the above drugs.

For severe paroxysms of fibrillation and atrial flutter that are refractory to drug treatment, surgical treatment methods are used.

Yuri BUNIN,

Professor of the Department of Cardiology of the Russian Medical Academy of Postgraduate Education.

Symptoms of AF

Depending on the form of arrhythmia (constant or paroxysmal) and the patient’s susceptibility, the clinical picture of AF varies from the absence of symptoms to the presence of signs of heart failure. Patients may complain of:

- interruptions in heart function;

- “bubbling” and/or chest pain;

- a sharp increase in heart rate;

- darkening of the eyes;

- general weakness, dizziness (against the background of hypotension);

- lightheadedness or fainting;

- a feeling of lack of air, shortness of breath and a feeling of fear.

Atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter may be accompanied by increased urination caused by increased production of natriuretic peptide. Attacks that last several hours or days and do not go away on their own require medical intervention.

Diagnostics

Diagnosis of atrial fibrillation includes:

- Analysis of patient complaints and anamnesis. It is determined when the interruptions in heart function began, whether chest pain occurs, or whether fainting occurred.

- Life history analysis. The doctor examines whether the patient has undergone any operations, whether he has chronic diseases or bad habits. It is also clarified whether any of the relatives suffered from heart disease.

- General blood test, urine test, biochemistry.

- Physical examination. The condition of the skin and its color are assessed. It is determined whether there are heart murmurs or wheezing in the lungs.

- Hormonal profile (carried out to study the level of thyroid hormones).

- Electrocardiography. The main ECG sign of atrial fibrillation is the absence of a wave, which reflects the normal synchronous contraction of the atria. Irregular heart rhythm is also detected.

- Holter monitoring of the electrocardiogram. The cardiogram is recorded over 1-3 days. As a result, the presence of asymptomatic episodes, the form of the disease, and the conditions contributing to the onset and termination of the attack are determined.

- Echocardiography. Aimed at studying structural cardiac and pulmonary changes.

- Chest X-ray. Shows increased size of the heart, changes that have occurred in the lungs.

- Treadmill test or bicycle ergometry. Assumes the use of stepwise increasing load.

- Transesophageal echocardiography. A probe with a special ultrasound sensor is inserted into the patient's esophagus. The method makes it possible to detect blood clots in the atria and their appendages.

Causes of AF and risk factors

Diseases of various origins

Most often, AF occurs in patients with diseases of the cardiovascular system - arterial hypertension, coronary artery disease, chronic heart failure, heart defects - congenital and acquired, inflammatory processes (pericarditis, myocarditis), heart tumors. Among the acute and chronic diseases not related to heart pathology, but affecting the occurrence of atrial fibrillation, there are dysfunctions of the thyroid gland, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, sleep apnea syndrome, kidney disease, etc.

Age-related changes

Atrial fibrillation is called “grandfather arrhythmia” because the incidence of this arrhythmia increases sharply with age. Electrical and structural changes in the atria may contribute to the development of this cardiac arrhythmia. However, experts note that atrial fibrillation can occur in young people who do not have heart pathology: up to 45% of cases of paroxysmal and up to 25% of cases of persistent fibrillation.

Other risk factors

Atrial fibrillation can develop due to alcohol consumption, electric shock, and open heart surgery. Paroxysms can be triggered by factors such as physical activity, stress, hot weather, and drinking too much. In rare cases, there is a hereditary predisposition to the occurrence of AF.

Causes

The main cause of atrial fibrillation is a malfunction of the conduction system of the heart, which causes a disturbance in the order of heart contractions. In such a situation, muscle fibers do not contract synchronously, but in discord; the atria cannot make one powerful push every second and instead tremble, not pushing the required amount of blood into the ventricles.

The causes of atrial fibrillation are conventionally divided into cardiac and non-cardiac. The first group includes:

- High blood pressure. With hypertension, the heart works harder and pushes out a lot of blood. The heart muscle cannot cope with the increased load, stretches and weakens significantly. Disturbances also affect the sinus node and conduction bundles.

- Valvular heart defects, heart diseases (cardiosclerosis, myocardial infarction, myocarditis, rheumatic heart disease, severe heart failure).

- Congenital heart defects (insufficient development of blood vessels feeding the heart, poor formation of the heart muscle are noted).

- Heart tumors (cause disturbances in the structure of the conduction system and do not allow impulses to pass through).

- Previous heart surgery. In the postoperative period, scar tissue may form, which replaces the unique cells of the cardiac conduction system. Because of this, the nerve impulse begins to travel along other paths.

The group of non-cardiac causes includes:

- physical fatigue;

- bad habits, alcohol;

- stress;

- large doses of caffeine;

- viruses;

- thyroid diseases;

- taking certain medications (diuretics, adrenaline, Atropine);

- chronic lung diseases;

- diabetes;

- electric shock;

- sleep apnea syndrome;

- electrolytic disturbances.

Diagnostic methods

First you need to determine your individual risk of stroke:

Determination of stroke risk during primary* (if no previous stroke) prevention (J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;38:1266i-1xx).

| Source | High risk | Medium risk | Low risk |

| Atrial Fibrillation Investigators (1)** | Age 65 years and older History of hypertension Diabetes | Age younger than 65 years No high-risk features | |

| American College of Chest Physicians (2) | Age over 75 years History of hypertension LV dysfunction *** More than 1 moderate risk factor | Age 65 - 75 years Diabetes IHD Thyrotoxicosis | Age under 65 No risk factors |

| Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation (3) | Women over 75 years of age Systolic blood pressure more than 160 mm Hg. Art. LV dysfunction** | History of hypertension No high-risk features | No high-risk features No history of hypertension |

Obtaining required data

Studying the patient's medical history and complaints. It is necessary to find out the specific symptoms that manifest atrial fibrillation, determine its clinical form, the date of appearance of the first signs, the frequency and duration of paroxysms, determine the predisposing factors and provoking diseases, and the effectiveness of the treatment.

Carrying out ECG, EchoCG. These examinations make it possible to determine the type of heart rhythm disturbances, assess the size of the heart chambers and the condition of the valves, and changes in myocardial contractility.

Blood test. To determine the function of the thyroid gland (T3, T4) and pituitary gland (TSH), to identify a lack of electrolytes (potassium) and signs of acute rheumatism or myocarditis.

Getting More Data

Holter monitoring ECG. 24-hour ECG recording allows you to monitor and evaluate heart rate at different times of the day (including sleep) during the patient’s normal daily routine, and to record attacks of AF.

Record AF paroxysms online. This type of Holter monitoring allows you to record electrocardiogram signals transmitted by telephone directly at the time of an attack.

Bicycle ergometry, treadmill test and other stress tests. These methods are used in cases where adequate control of heart rate is not established (in chronic AF), to provoke arrhythmia caused by exercise, as well as to exclude cardiac ischemia before treatment with class 1C antiarrhythmics.

Transesophageal echocardiography. This test helps identify the presence of a thrombus in the left atrium before cardioversion.

Electrophysiological study. EPI is performed to explain the mechanism of tachycardia, identify and surgically treat predisposing arrhythmia (radiofrequency ablation).

AF treatment strategies

There are two main strategies used to treat patients with atrial fibrillation:

- rhythm control – restoration of sinus rhythm (drug or electrical cardioversion with subsequent prevention of relapse;

- rate control – heart rate control combined with anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapy (if AF persists).

The treatment strategy for a particular patient is chosen depending on many factors, and, first of all, the form of the disease - paroxysmal or persistent atrial fibrillation. So, in the first case, the attack must be stopped (this is especially true for the very first manifestation of AF). With a persistent form of atrial fibrillation, constant medication is prescribed to control heart rate and prevent stroke.

According to the results of recent studies, the use of propafenone provides high efficiency in restoring and maintaining sinus rhythm. Following the VNOK recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of fibrillation, this drug is classified as the first line of drugs used for persistent AF for pharmacological cardioversion (class I, level of evidence A).

Treatment

Conservative treatment of atrial fibrillation (atrial fibrillation)

Atrial fibrillation is a risk factor for ischemic stroke, which develops as a result of the formation of blood clots in the cavity of the left atrium. The first-line treatment for atrial fibrillation is drugs that prevent blood clots. They are prescribed by a doctor, because... monitoring of the blood coagulation system is required. These drugs are indicated for almost all patients who suffer from atrial fibrillation, regardless of whether the arrhythmia is constantly present or occurs in attacks (paroxysmal form of arrhythmia). The risk of stroke is the same both in the presence of a chronic form of arrhythmia and in a paroxysmal form of arrhythmia.

In patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, the issue of preventing the occurrence of arrhythmia attacks is addressed. If the attack occurs for the first time, antiarrhythmic drugs are not prescribed. Medications may be recommended to control heart rate and improve tolerance to repeated episodes of arrhythmias. Antiarrhythmic drugs are also not prescribed if the patient’s arrhythmia attacks are asymptomatic and do not reduce his quality of life. If rhythm disturbances recur and paroxysm tolerance deteriorates, the cardiologist-arrhythmologist, together with the patient, decides on the prescription of antiarrhythmic drugs or surgical treatment of arrhythmia (catheter ablation).

If a prolonged attack of atrial fibrillation develops, which does not go away on its own, it is necessary to contact a specialist cardiologist-arrhythmologist, who will choose the most suitable method for stopping the arrhythmia for the patient. A technique for medicinal restoration of normal heart rhythm has been developed, as well as a procedure for restoring rhythm using electrical cardioversion. To restore the rhythm, a certain medication preparation is necessary, the regimen of which will be determined by the doctor, based on the individual characteristics of the course of the disease. With the advent of the latest highly effective antiarrhythmic drugs, preference is given to drug restoration of rhythm.

When transforming the paroxysmal form of atrial fibrillation into a chronic form, the main task is to control the heart rate. In the presence of tachysystole (high heart rate), drugs are prescribed that reduce the heart rate, the primary of which are beta-blockers. An integral part of the treatment of atrial fibrillation is the treatment of the disease that provoked the rhythm disturbance - coronary heart disease, heart failure, arterial hypertension, disorders of the thyroid gland and others.

It is necessary to contact a cardiologist-arrhythmologist if:

- development of an attack of atrial fibrillation for the first time in life,

- development of another attack of arrhythmia that cannot be controlled by usual means,

- ineffectiveness of previously prescribed antiarrhythmic therapy.

Use of the drug Propanorm for AF

Relief of paroxysms

The strategy, called the “pill in the pocket,” is based on taking a loading dose of Propanorm, which allows you to restore the heart rhythm both in hospital and outpatient treatment. According to many placebo-controlled studies, the effectiveness of a single oral dose of 450-600 mg of propafenone ranges from 56 to 83% (Boriari G, Biffi M, Capucci A, et al., 1997). According to the all-Russian study "PROMETHEUS", which involved 764 patients with recurrent atrial fibrillation, the effectiveness of the loading dose of the drug was 80.2%.

Prevention of paroxysms

The strategy is based on taking the drug daily to prevent paroxysms. The multicenter, open-label, randomized, prospective comparative study "Prostor" provided the following preliminary results.

- Propanorm® does not lead to a deterioration in hemodynamic parameters in patients with arterial hypertension, coronary heart disease and chronic heart failure with preserved systolic function. The use of the drug for atrial fibrillation for prophylactic purposes helps reduce the number of hospitalizations associated with circulatory decompensation by 72.9%.

- The antiarrhythmic effectiveness of Propanorm after 12 months from the start of administration is almost equal to the indicators when using Cordarone - 54.2% and 52.9%, respectively.

- In the absence of post-infarction cardiopathy (ejection fraction less than 40%), Propanorm® can be used as an antiarrhythmic drug, including in combination with beta-blockers, if necessary.

- Propanorm® has a better safety profile compared to Cordarone.

To maintain sinus rhythm in patients diagnosed with recurrent atrial fibrillation, the recommended daily dose for continuous use of Propanorm is 450 mg (3 times a day) or 600 mg (2 times a day). With frequent occurrence of paroxysms, it is possible to increase the dose to 900 mg (3 times a day).

Epidemiology of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation and flutter are the most common and dangerous types of heart rhythm disturbances and occur in 0.4–1.0% of cases in the population [1, 2].

The incidence of atrial fibrillation/flutter increases with age. According to the Framingham Study, the incidence of atrial fibrillation (AF) doubles every 10 years of life: 0.55% in patients aged 50–59 years and 8.8% in patients aged 81–90 years [3]. Over the past 20 years, there has been a trend towards an increase in the incidence of AF, especially among men. In addition, there has been an increase in the number of hospitalizations for MA; in the USA, for example, this parameter increased 2.5 times over the period from 1985 to 1999 [4, 5]. The negative impact of atrial fibrillation/flutter was also studied: the risk of thromboembolic complications increased by 4–5 times, the mortality rate by 1.5–2.0 times [6, 7]. This pathology can lead to the development and progression of heart failure and a decrease in quality of life. Among patients hospitalized for cardiac arrhythmias, AF occurs in 34%, atrial flutter – in 4% of cases.

As a rule, at the very beginning, MA is paroxysmal. The prevalence of AF paroxysms varies, according to various sources, in the range of 22–65%. Of these, in 35–78% of cases, the paroxysmal form of arrhythmia becomes persistent [8].

Definition, classification of paroxysms of flickering

The term “paroxysmal atrial fibrillation” refers to a rhythm disturbance associated with chaotic contraction of individual groups of atrial muscle fibers, lasting no more than 7 days with the possibility of spontaneous relief. The frequency of atrial waves can reach up to 600 beats/min. Due to the variability of atrioventricular conduction under these conditions, partly due to the hidden conduction of some impulses, the ventricles contract randomly. In the absence of additional disturbance of atrioventricular conduction, the ventricular rate is about 100–150 beats per minute (tachysystolic atrial fibrillation). It is believed that the electrophysiological basis of atrial fibrillation is multiple small circles of impulse circulation in the atrial myocardium. Attacks of atrial fibrillation, especially the normo- and bradysystolic forms, often do not cause pronounced hemodynamic disorders and may not be accompanied by a noticeable deterioration in the patient’s condition and well-being.

In terms of prescribing differentiated therapy, it is noteworthy to distinguish two forms of paroxysmal MA: with a predominance of the tone of the parasympathetic nervous system (“vagal” paroxysmal MA) and with a predominance of the tone of the sympathetic nervous system (“adrenergic”, “catecholamine” paroxysmal arrhythmia) [9].

Definition, classification of flutter paroxysms

Atrial flutter is a regular contraction of the atria at a rate of about 250–350 beats per minute. The ventricular rhythm may be regular or irregular. The frequency and regularity of the ventricular rhythm during atrial flutter is determined by atrioventricular conduction, which can change. Atrial flutter occurs 10–20 times less frequently than paroxysmal fibrillation. Sometimes atrial fibrillation and flutter alternate in one patient. The term “atrial fibrillation” was proposed by G.F. Lang to designate atrial fibrillation and flutter due to the commonality of some pathogenetic and clinical features, however, in the diagnosis, arrhythmia must be specifically designated as fibrillation or flutter.

With the paroxysmal form of flutter, the frequency of paroxysms can be very different: from once a year to several times a day. Paroxysms can be triggered by physical activity, emotional stress, hot weather, drinking too much, alcohol, and even intestinal upset. Paroxysms sometimes go away on their own, but sometimes drug treatment is required. Some people with MA do not feel it, while others notice a slight irregularity in their heart rhythm. You may also experience dizziness, pressure, and chest pain.

Atrial flutter, being one of the forms of AF, differs little in clinical manifestations from atrial fibrillation, but is characterized by somewhat greater persistence of paroxysms and greater resistance to antiarrhythmic drugs. There are regular (rhythmic) and irregular forms of this arrhythmia. The latter is clinically more similar to atrial fibrillation. In addition, there are two main types of atrial flutter: 1 – classic (typical); 2 – very fast (atypical) [10].

Pathogenesis of atrial fibrillation/flutter

It was found that AF is predominantly an atrial tachyarrhythmia, which begins and forms in the left atrium, where several microreentry circles occur. Atrial flutter, on the other hand, usually occurs in the right atrium - in its lower part. The macroreentry circle, which underlies atrial flutter, is located mainly in the area (bridge) of the right atrium connecting the mouth of the inferior vena cava and the tricuspid valve annulus. Naturally, in our time, methods of treating paroxysms of atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter - these two related, but still different atrial tachyarrhythmias - should be considered separately.

Diagnosis of atrial fibrillation/flutter

In AF, the electrocardiogram (ECG) shows no P wave, diastole is filled with small waves of irregular configuration and rhythm, more noticeable in lead VI. Their frequency is 300–600 beats per minute (usually not counted). Ventricular complexes follow an irregular rhythm and are usually not deformed. With a very fast ventricular rhythm (more than 150 beats/min), blockade of the leg, usually the right one, of the atrioventricular bundle is possible. Under the influence of treatment, as well as in the presence of atrioventricular conduction disturbances along with atrial fibrillation, the ventricular rate may be lower. At a frequency of less than 60 beats/min, we speak of the bradysystolic form of atrial fibrillation. Occasionally, atrial fibrillation is combined with complete atrioventricular block. At the same time, the ventricular rhythm is rare and regular. In persons with paroxysms of atrial fibrillation, when recording an ECG outside the paroxysm, especially soon after it, a more or less pronounced deformation of the P wave is often detected.

With atrial flutter, the ECG reveals regular atrial waves without diastolic pauses, having a characteristic sawtooth appearance, more clearly expressed in lead AVF. Atrial waves fill the ventricular diastole, they are also superimposed on the ventricular complexes, slightly deforming them. Ventricular complexes can follow rhythmically - after every second (then the ventricular rhythm is about 120-160 beats / min), third, etc. atrial wave, or arrhythmically, if the ratio of atrial and ventricular contractions is not constant. With a frequent ventricular rhythm, a violation of intraventricular conduction is possible, more often - blockade of the right leg of the atrioventricular bundle. With a frequent and regular ventricular rhythm, flutter is difficult to distinguish by ECG from other supraventricular tachycardias. If it is possible to temporarily reduce atrioventricular conduction (using carotid sinus massage, digoxin or 5 mg verapamil), the ECG picture becomes more characteristic.

Treatment of atrial fibrillation

When treating patients with atrial fibrillation and flutter at the prehospital stage, the feasibility of restoring sinus rhythm should be assessed. The absolute indication for restoration of sinus rhythm during the development of paroxysmal AF is the development of pulmonary edema or arrhythmogenic shock. In this case, emergency cardioversion should be performed prehospital.

Contraindications to restoring sinus rhythm at the prehospital stage include:

- the duration of paroxysm of atrial fibrillation is more than two days;

- proven dilatation of the left atrium (antero-posterior size 4.5 cm, according to echocardiography);

- presence of blood clots in the atria or a history of thromboembolic complications;

- development of paroxysm against the background of acute coronary syndrome (in the presence of stable hemodynamics);

- development of paroxysm against the background of pronounced electrolyte disturbances;

- decompensation of thyrotoxicosis;

- severe chronic hemodynamic disorders and some others.

In such cases, treatment should be aimed at stabilizing hemodynamics, preventing thromboembolism and controlling the heart rate in order to maintain it within 60–90 beats/min.

The drug of choice for heart rate control is cardiac glycosides, particularly digoxin. Further tactics are determined in the hospital. Persistent normosystolic form of AF without signs of heart failure does not require antiarrhythmic therapy at all [11].

It is known that 50–60% of recently developed (less than 48 hours) paroxysms of AF cease spontaneously. S. Ogawa et al. [12] in the J-RHYTHM study found that parameters such as mortality and the number of complications when stopping paroxysms of atrial fibrillation do not depend on the chosen treatment tactics (lowering the heart rate or restoring sinus rhythm). Similar results were obtained in their study by SH Hohnloser et al. [13].

Starting to characterize the methods of drug treatment of paroxysms of AF, we consider it necessary to emphasize that an antiarrhythmic drug has not yet been synthesized that can eliminate paroxysms of atrial fibrillation in every patient. The doctor must have a set of various effective drugs in order to be able to adequately replace one drug with another. Typically, treatment of AF paroxysm begins with an intravenous infusion of potassium chloride solution, often together with digoxin. Potassium chloride itself often eliminates paroxysms of AF after 3–5 infusions. In addition, an increase in plasma potassium concentration by 0.5–1.5 µm/l creates a favorable background for the subsequent action of other antiarrhythmic drugs.

In case of failure with the use of cardiac glycoside and potassium chloride or in the presence of contraindications to the use of cardiac glycosides, procainamide is administered. If necessary, this can be done earlier, for example, after 1-2 infusions of potassium chloride solution. According to the observations of various authors, the results of treatment of AF with procainamide are noticeably improved if it is administered to patients 20–30 minutes after intravenous infusion of a solution of potassium chloride and cardiac glycoside. In this way, sinus rhythm was restored in 65% of patients who did not respond at the prehospital stage to a sufficiently large dose of procainamide (up to 15 ml of a 10% solution) administered intravenously [14].

Effective antiarrhythmic drugs that are recommended for clinical use for the purpose of conversion of atrial AF are the IC class drugs propafenone and flecainide. They are effective when administered intravenously and orally. Sinus rhythm in patients with AF is restored 2–6 hours after oral administration. According to a placebo-controlled study by Yu.A. Bunina et al. [15], the effectiveness of propafenone in AF (single oral dose of 600 mg, observation for 8 hours) is about 80%. However, several randomized controlled studies emphasize the limited ability of intravenously administered propafenone to convert atrial flutter (no more than 40%). Our observations also indicate a rather low effectiveness of propafenone in the oral treatment of atrial flutter.

The use of class IC antiarrhythmics is contraindicated in patients with acute myocardial ischemia (unstable angina, myocardial infarction). A meta-analysis showed that antiarrhythmics of classes IC, IA and III have approximately the same effectiveness in stopping AF. However, no evidence was found of any effect of these drugs on the survival and quality of life of patients [16].

If a paroxysm of AF is preceded by an increase in sinus rhythm, if the paroxysm occurs in the daytime under the influence of stressors, physical or emotional stress, it must be assumed that the basis of such paroxysm is a hypersympathicotonic mechanism. Verapamil, diltiazem and β-blockers are first-line drugs for emergency intravenous reduction of heart rate, because these antiarrhythmics are highly effective and quickly (within 5-10 minutes) exert their effect. With intravenous digoxin, a sustained slowdown in ventricular rate is achieved much later (after 2–4 hours). For patients with a high risk of systemic embolism (atrial fibrillation/flutter lasting more than 2 days), in order to reduce the heart rate, amiodarone is a reserve drug, after the use of which it is possible to restore sinus rhythm and, consequently, the appearance of “normalizing” thromboembolism [17].

A number of international recommendations [18, 19] note that the relief of paroxysmal fibrillation/flutter in patients with heart failure or a left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 40% should be carried out with amiodarone. Other antiarrhythmics should be used with caution or not be used due to the relatively high risk of developing arrhythmogenic effects and negative effects on hemodynamics. A meta-analysis of the results of placebo-controlled studies of cardioversion of AF with amiodarone showed late relief of arrhythmia paroxysms: a significant difference in effectiveness between amiodarone and placebo was noted no earlier than 6 hours after their intravenous use. Taking this into account, after an intravenous “loading” dose of amiodarone is administered, it is then advisable to continue its intravenous infusion for 6–2 hours.

In a study by R.D. Kurbanova et al. [20] found that a course of treatment with a saturating dose of amiodarone helps restore sinus rhythm in 30% of patients with dilated cardiomyopathy complicated by AF. At the same time, long-term treatment with amiodarone helps maintain sinus rhythm in the next 6 months and compensates for heart failure. A meta-analysis also showed that treatment with amiodarone facilitates the procedure for restoring sinus rhythm and has a positive effect on patient survival [21].

In the study by S.A. Filenko [22] found that in patients with coronary heart disease, the paroxysmal form of AF occurs in the sympathetic and mixed types. In a study of drugs that have an anti-relapse effect on paroxysmal fibrillation, it was shown that amiodarone is the most effective, and in patients with paroxysmal AF of the sympathetic type, metoprolol also turned out to be effective.

S.A. Starichkov et al. [23] studied patients with arterial hypertension (AH) suffering from AF. Analysis of the results showed that the use of a combination of amiodarone and metoprolol for hypertension makes it possible to reduce the doses of antiarrhythmic drugs used and contributes not only to more effective control of blood pressure levels, but also to the prevention of AF paroxysms in 71% of patients. The use of β-blockers, both as monotherapy and in combination with amiodarone, leads to normalization of heart rate variability and has a positive effect on the processes of myocardial remodeling in various chambers of the heart.

It is known that blockade of type 1 angiotensin II receptors, in addition to lowering blood pressure, can lead to a decrease in myocardial remodeling and hypertrophy, normalization of electrolyte balance, and has indirect anti-ischemic and anti-adrenergic effects [24]. In the study by Yu.G. Schwartz et al. [25] treatment with losartan in patients with a combination of paroxysms of AF and hypertension was accompanied by a significant decrease in the frequency of arrhythmia paroxysms, in contrast to patients treated with nifedipine and atenolol. The authors believe that the likely mechanism for the positive effect of losartan on the course of AF paroxysms is a direct effect on the myocardium. Even J. Mayet [26] suggested that regression of left ventricular hypertrophy is associated with the antiarrhythmic effect of antihypertensive therapy.

One promising avenue for the treatment of arrhythmias is the use of omega-3-polyunsaturated fatty acids (ω-3-PUFA). In 2005, a study was published showing that consumption of fatty fish rich in long-chain ω-3-PUFA may reduce the risk of AF [27]. The authors explained this antiarrhythmic effect of ω-3-PUFA by reducing blood pressure and improving left ventricular diastolic function.

I.V. Antonchenko et al. [28] found that one of the possible mechanisms of the protective effect of ω-3-PUFA in patients with paroxysmal AF is reverse electrical remodeling of the atrial myocardium. The addition of ω-3-PUFAs to relief therapy reduces the number of episodes of AF and the time of their relief. However, the electrophysiological effects of using ω-3-PUFA at a dose of 1 g/day occur no earlier than the 20th day of administration.

The treatment tactics for paroxysms of atrial flutter largely depend on the severity of hemodynamic disorders and the patient’s well-being. This arrhythmia often does not cause severe hemodynamic disturbances and is little felt by the patient even with significant ventricular tachysystole. In addition, such paroxysms are usually difficult to stop with intravenous administration of antiarrhythmics, which can even cause a deterioration in the patient’s condition. Therefore, in these cases, emergency treatment is usually not required.

Speaking about drug treatment of this arrhythmia, it should be borne in mind that, according to the authors of the “Sicilian Gambit” concept [29], paroxysms of type I atrial flutter are better controlled by class IA drugs (quinidine, procainamide, disopyramide). However, when using drugs of this class there is a risk of paradoxical acceleration of the ventricular rate, so it is better to first use verapamil or beta-blockers. Paroxysms of type II atrial flutter are better controlled by class I3 drugs, in particular amiodarone. Domestic authors note the high effectiveness of nibentan in relieving paroxysms of fibrillation and especially atrial flutter [30].

It has now been proven that mental disorders worsen the course of arrhythmias, in particular AF, by complicating clinical manifestations and reducing quality of life. There is also an opinion that patients with depressive disorders have a violation of the autonomic regulation of heart rhythm (decreased parasympathetic and increased sympathetic tone), which increases the risk of AF.

In the study by B.A. Tatarsky et al. [31] the addition of Afobazole was accompanied by a pronounced anxiolytic effect without severe sedation, effective correction of autonomic disorders, and the absence of drug dependence and withdrawal syndrome. It was found that Afobazole treatment of patients with paroxysmal AF without pronounced structural changes in the heart was accompanied by a decrease in the frequency of paroxysms, the duration of arrhythmia episodes, and easier tolerability; there was a tendency to transform into an asymptomatic form.