If an attack (paroxysm) of atrial fibrillation lasts longer than two days, the risk of blood clots and the development of ischemic stroke increases sharply. With a constant form of arrhythmia, chronic circulatory failure can progress.

According to statistics, atrial fibrillation accounts for 30% of all hospitalizations associated with arrhythmia. The disease occurs more often in elderly patients over 60 years of age.

Classification of atrial fibrillation

Taking into account the characteristics of the clinical course, electrophysiological mechanisms and etiological factors, cardiologists classify the disease as follows:

- chronic or permanent form of atrial fibrillation (symptoms remain pronounced, electrical cardioversion is ineffective);

- persistent form of atrial fibrillation (lasts more than a week);

- transient or paroxysmal form of atrial fibrillation (the attack lasts from 1 to 7 days).

Persistent and paroxysmal forms of atrial fibrillation are often recurrent. They also distinguish between a newly diagnosed attack of atrial fibrillation and a recurrent one.

Atrial fibrillation and flutter

The disease can occur in two different types of atrial disorders - fibrillation and atrial flutter. During fibrillation, only individual groups of muscle fibers contract, resulting in no coordinated contraction. As a result, a large number of electrical impulses are concentrated in the atrioventricular connection. Some of them spread to the ventricular myocardium, others are delayed.

Based on the frequency of ventricular contractions, atrial fibrillation comes in three forms:

- bradysystolic (less than 60 ventricular contractions per minute);

- normosystolic (from 60 to 90 contractions);

- tachysystolic (more than 90 ventricular contractions per minute).

In paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, blood is not pumped into the ventricles. The atria do not contract effectively enough, which is why at the moment of relaxation (diastole), the ventricles are only partially filled with blood. Consequently, the release of blood into the aortic system does not always occur.

With flutter, rapid atrial contraction is noted (200 - 400 per minute), the correct coordinated atrial rhythm is maintained. In this case, myocardial contractions follow each other almost without interruption, the diastolic pause practically does not occur, the atria cannot relax and are in a state of systole most of the time. They are not completely filled with blood, and its flow into the ventricles decreases.

Causes

The main cause of atrial fibrillation is a malfunction of the conduction system of the heart, which causes a disturbance in the order of heart contractions. In such a situation, muscle fibers do not contract synchronously, but in discord; the atria cannot make one powerful push every second and instead tremble, not pushing the required amount of blood into the ventricles.

The causes of atrial fibrillation are conventionally divided into cardiac and non-cardiac. The first group includes:

- High blood pressure. With hypertension, the heart works harder and pushes out a lot of blood. The heart muscle cannot cope with the increased load, stretches and weakens significantly. Disturbances also affect the sinus node and conduction bundles.

- Valvular heart defects, heart diseases (cardiosclerosis, myocardial infarction, myocarditis, rheumatic heart disease, severe heart failure).

- Congenital heart defects (insufficient development of blood vessels feeding the heart, poor formation of the heart muscle are noted).

- Heart tumors (cause disturbances in the structure of the conduction system and do not allow impulses to pass through).

- Previous heart surgery. In the postoperative period, scar tissue may form, which replaces the unique cells of the cardiac conduction system. Because of this, the nerve impulse begins to travel along other paths.

The group of non-cardiac causes includes:

- physical fatigue;

- bad habits, alcohol;

- stress;

- large doses of caffeine;

- viruses;

- thyroid diseases;

- taking certain medications (diuretics, adrenaline, Atropine);

- chronic lung diseases;

- diabetes;

- electric shock;

- sleep apnea syndrome;

- electrolytic disturbances.

Etiology of AF and cardiovascular risks

Atrial fibrillation is defined as a supraventricular tachyarrhythmia characterized by chaotic electrical activity of the atria at a high rate (350-700 per minute) and an irregular ventricular rhythm1. Previously, the term “atrial fibrillation” was widely used, which quite accurately conveys the essence of atrial fibrillation.

According to foreign studies, AF is the most common form of tachyarrhythmia in the world and occurs in 2% of the population2. There are valvular and non-valvular AF (NVAF). In the first case, AF is associated with damage to the heart valves and overload of the left atrium with pressure or volume, due to which fibrillation begins. The most common cause of valvular AF is rheumatic mitral valve stenosis or replacement1. All other cases of atrial fibrillation are defined as non-valvular.

NFP occurs against the background of a number of diseases and conditions, such as coronary heart disease, hypertension, primary myocardial diseases, diabetes mellitus, pheochromocytoma, as well as alcohol abuse, excess body weight and hypokalemia3. Due to the chaotic movement of blood in the fibrillating left atrium, the prerequisites are created for the formation of blood clots, which can spread through the left ventricle throughout the systemic circulation. Thromboembolic complications are the most dangerous complications of AF. These include:

- ischemic cardioembolic stroke;

- heart attacks of internal organs;

- thromboembolism of the vessels of the extremities.

In a cardioembolic stroke, an embolus (thrombus) located in the left atrium breaks off and enters the arterial system of the brain.

According to a number of epidemiological studies, NFP increases the risk of stroke by 2.6-4.5 times, depending on the clinical parameters of patients4. Moreover, for women, these risks, other things being equal, are higher than for men5.

A stroke that occurs during NAF is severe and more often leads to disability than a stroke in patients without AF6. The basis for the prevention of thromboembolism in NFP is oral anticoagulants. They reduce the activity of blood clotting and thus prevent the formation of emboli (blood clots). 10 years ago, the drug of choice was the vitamin K antagonist warfarin, but direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) appeared, in particular apixaban, which have a number of advantages over warfarin, which allowed DOACs to become the standard for stroke prevention in NAF.

Symptoms of atrial fibrillation

Symptoms of atrial fibrillation depend on:

- myocardial conditions;

- forms of the disease;

- features of the valve apparatus.

The worst case for patients is the tachysystolic form of atrial fibrillation. They experience:

- dyspnea;

- cardiopalmus;

- heartache;

- feeling of a sinking heart;

- pulsation of neck veins.

Typical cases of the disease are characterized by:

- sweating;

- randomness of heartbeats;

- unreasonable fear;

- shiver;

- polyuria.

If the heart rate is very high, Morgagni-Adams-Stokes attacks and fainting appear. As soon as sinus heart rhythm is restored, these symptoms disappear.

Over the years, those suffering from a chronic (permanent) form of atrial fibrillation generally cease to notice it.

If you experience similar symptoms,

consult your doctor . It is easier to prevent a disease than to deal with the consequences.

Diagnostics

Diagnosis of atrial fibrillation includes:

- Analysis of patient complaints and anamnesis. It is determined when the interruptions in heart function began, whether chest pain occurs, or whether fainting occurred.

- Life history analysis. The doctor examines whether the patient has undergone any operations, whether he has chronic diseases or bad habits. It is also clarified whether any of the relatives suffered from heart disease.

- General blood test, urine test, biochemistry.

- Physical examination. The condition of the skin and its color are assessed. It is determined whether there are heart murmurs or wheezing in the lungs.

- Hormonal profile (carried out to study the level of thyroid hormones).

- Electrocardiography. The main ECG sign of atrial fibrillation is the absence of a wave, which reflects the normal synchronous contraction of the atria. Irregular heart rhythm is also detected.

- Holter monitoring of the electrocardiogram. The cardiogram is recorded over 1-3 days. As a result, the presence of asymptomatic episodes, the form of the disease, and the conditions contributing to the onset and termination of the attack are determined.

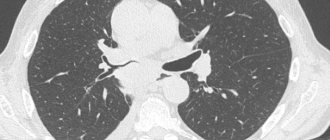

- Echocardiography. Aimed at studying structural cardiac and pulmonary changes.

- Chest X-ray. Shows increased size of the heart, changes that have occurred in the lungs.

- Treadmill test or bicycle ergometry. Assumes the use of stepwise increasing load.

- Transesophageal echocardiography. A probe with a special ultrasound sensor is inserted into the patient's esophagus. The method makes it possible to detect blood clots in the atria and their appendages.

Publications in the media

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is chaotic, irregular excitation of individual atrial muscle fibers or groups of fibers with loss of mechanical atrial systole and irregular, not always complete excitations and contractions of the ventricular myocardium. Clinical characteristic: atrial fibrillation.

Etiology • Rheumatic heart defects • IHD • Thyrotoxic heart • Cardiomyopathies • Arterial hypertension • Myocardial • COPD • PE • Condition after coronary artery bypass surgery • Vagotonia • Hypersympathicotonia • Hypokalemia • Idiopathic AF • Combinations of etiological factors.

Classification • Newly identified •• Paroxysmal - lasting up to 7 days, self-limiting •• Persistent - duration usually more than 7 days, not self-limiting •• Permanent form: cardioversion (CV) is ineffective or not indicated • According to the frequency of ventricular responses •• Tachysystolic form — AF with a ventricular activation rate of more than 90 per minute •• Normosystolic form ¾ with a ventricular contraction rate of 60–90 per minute •• Bradysystolic form — AF with a ventricular contraction rate of less than 60 per minute • Special forms •• AF in Wolff–Parkinson syndrome– White •• AF with sick sinoatrial node syndrome (brady-tachycardia syndrome) •• AF with complete AV block (Frederick's syndrome) • According to ECG parameters •• Large-wave AF - ff wave amplitude more than 0.5 mV, frequency 350 –450 per minute. QRS complexes are not the same in shape •• Medium-wave AF - the amplitude of ff waves is less than 0.5 mV, frequency 500-700 per minute •• Small-wave AF - difficult to distinguish ff waves.

Clinical manifestations • Vary from moderate weakness, palpitations, shortness of breath, dizziness and fatigue to severe heart failure, angina attacks, fainting • The most pronounced subjective sensations are with diastolic myocardial dysfunction, as well as tachysystole or bradysystole.

Differential diagnosis • Atrial flutter - lower frequency, contractions more regular • Atrial multifocal paroxysmal tachycardia is characterized by synchronous depolarization of the atria, but the pacemakers are two or more ectopic foci in the atria, alternately generating impulses. Atrial polytopic tachycardia is often observed in severe lung diseases, intoxication with cardiac glycosides, coronary heart disease and pulmonary embolism. Characterized by variability of the P wave and unequal R–R intervals.

TREATMENT

Therapeutic tactics • Assessment of the circulatory state • Carrying out electropulse therapy (EPT) for urgent indications • Pharmacological CV - in the absence of urgent indications or necessary conditions for EIT • Pharmacological control of heart rate before conducting CV and with a permanent form of AF • With a duration of AF more than 2 days - prescription of indirect anticoagulants for 3-4 weeks before and after CI (exception - patients with idiopathic AF under 60 years of age) •• Prevention of relapses of AF.

Restoration of sinus rhythm - contraindications: • Duration of AF for more than 1 year - unstable effect of CV does not justify the risk of its implementation • Atriomegaly and cardiomegaly (mitral valve disease, dilated cardiomyopathy, left ventricular aneurysm) - CV is performed only for urgent indications • Bradysystolic form of AF - after elimination AF often reveals sick sinoatrial node syndrome or AV block • Presence of thrombi in the atria • Uncorrected thyrotoxicosis.

EIT

• Indications: AF with signs of increasing heart failure, a sharp drop in blood pressure, and pulmonary edema.

• Method of implementation - see Electrical cardioversion.

• The prognosis is elimination of AF in 95% of cases.

• Complications of CV •• Thromboembolism during prolonged paroxysm of AF (for 2–3 days or more) due to the formation of intra-atrial thrombi (so-called normalization thromboembolism) ••• It is recommended before electrical CV (as well as before pharmacological) if AF lasts more than 2 days A 3–4-week course of therapy with indirect anticoagulants to prevent thromboembolism ••• Transesophageal echocardiography performed before EIT allows one to exclude a thrombus located in the left atrial appendage (the most common location of intra-atrial thrombi) and conduct early CV with heparin administration followed by indirect anticoagulants for 3–4 weeks • • Atrial asystole - see Atrial asystole.

Pharmacological CV is most effective with early restoration of sinus rhythm (duration of AF 7 days or less). The administration of antiarrhythmic drugs should be carried out under constant ECG monitoring against the background of correction of hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia.

• Procainamide 10–15 mg/kg IV, infusion at a rate of 30–50 mg/min, see Atrial flutter. In case of renal failure, the dose of the drug is reduced.

• Propafenone 2 mg/kg IV over 5–10 minutes. Orally 450–600 mg at once or 150–300 mg 3 times a day for 1–2 weeks. Indicated in the absence or minimally expressed structural changes in the myocardium.

• Amiodarone 5 mg/kg IV drip over 10–15 min (rate 15 mg/min) or 150 mg over 10 min, then either infusion 1 mg/kg over 6 hours, or orally 30 mg/kg (10–12 tablets) once, or 600–800 mg per day for 1 week, then 400 mg per day for 2–3 weeks. Indicated for patients with reduced myocardial contractile function.

• A combination of quinidine 200 mg orally 3–4 times a day with verapamil 40–80 mg orally 3–4 times a day is effective. Sinus rhythm is restored in 85% of patients on days 3–11.

Monitoring heart rate in a permanent form of AF and before CA: the choice of drug is determined by the underlying pathology (thyrotoxicosis, myocarditis, MI, etc.), as well as the severity of heart failure.

• Verapamil. It is especially indicated for concomitant COPD and peripheral arterial disease. Arterial hypotension may develop. Combination with IV beta-blockers is contraindicated. Regimens: •• IV 5–10 mg over 2–3 minutes, if necessary, repeat after 30 minutes with another 5 mg IV, the initial effect can be maintained by infusing the drug at a constant rate of 0.005 mg/kg/min •• • orally 40–80–160 mg 3 times a day.

• Diltiazem - 25 mg IV over 2-3 minutes or IV drip at a rate of 0.05-0.2 mg/min. Orally 120–360 mg per day.

• b-Adrenergic blockers. Indicated for hypersympathicotonia, thyrotoxicosis. Arterial hypotension may develop. Drugs: propranolol IV slowly over 5-10 minutes 1-12 mg under blood pressure control or metoprolol 5-15 mg IV. Orally, 20–40–80 mg of propranolol 3–4 times a day.

• Cardiac glycosides are indicated for persistent AF, especially for AF with reduced ventricular systolic function; contraindicated in the presence of Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome • • Rapid rate of saturation ••• Digoxin 0.5 mg IV over 5 minutes, repeat the dose after 4 hours, then 0.25 mg twice with an interval of 4 hours (total 1 .5 mg per 12 hours) ••• Digoxin 0.5 mg IV for 5 minutes, then 0.25 mg every 2 hours (4 times) ••• If intoxication with cardiac glycosides develops, potassium chloride solution in /in drip, see Intoxication with cardiac glycosides • • Average rate of saturation ••• Intravenous infusion of 1 ml of 0.025% digoxin solution (or 1 ml of 0.025% strophanthin K solution) and 20 ml of 4% potassium chloride solution in 150 ml of 5% glucose solution at a rate of 30 drops/min daily •••• Digoxin, first 0.75 mg orally, then 0.5 mg every 4–6 hours. The average dose for saturation is 2.5 mg.

• If monotherapy with digoxin, beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers is ineffective, various combinations of them should be used. When verapamil is combined with digoxin, the level of the latter in the blood may increase significantly; the dose of digoxin should be reduced.

Treatment of AF due to Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome - see Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome.

Relapse Prevention

• Selection of doses of antiarrhythmic drugs (amiodarone, quinidine, procainamide, etacizine, propafenone, etc.) with monitoring of hemodynamic parameters and ECG. Long-term use of antiarrhythmic drugs, especially subclass Ic, for the prevention of AF increases mortality in patients with post-infarction cardiosclerosis and impaired myocardial contractile function (see Cardiac Arrhythmias).

• Treatment of the underlying disease.

• Elimination of factors that provoke arrhythmia, such as psycho-emotional stress, fatigue, stress, consumption of alcohol, coffee and strong tea, smoking, hypokalemia, viscero-cardiac reflexes in diseases of the abdominal organs, anemia, hypoxemia, etc.

Surgical treatment is used in cases of severe clinical manifestations and ineffectiveness of drug therapy • An alternative method is radiofrequency catheter destruction of the atrioventricular node with implantation of a permanent pacemaker (if heart rate control with pharmacological drugs is ineffective or severe adverse reactions) • Radiofrequency destruction of the pulmonary veins in AF caused by the presence of foci of automaticity in this area • Implantation of atrial defibrillators that automatically record and eliminate attacks of AF through the generation of an electrical impulse • Open “corridor” and “maze” operations, as well as isolation of the pulmonary veins, are usually performed in combination with other open-heart interventions (valve replacement and etc.). In a small number of clinics, these same procedures are performed endovascularly.

Complications • Cardiogenic embolic stroke • Peripheral arterial embolism • Bleeding during anticoagulant therapy.

Course and prognosis • The risk of stroke is small with long-term anticoagulant therapy • AF increases the risk of death from cardiovascular disease.

Synonym . Atrial fibrillation.

Abbreviations • AF - atrial fibrillation • EIT - electrical pulse therapy • CV ¾ cardioversion.

ICD-10 • I48 Atrial fibrillation and flutter

Treatment of atrial fibrillation

Treatment of atrial fibrillation is aimed at:

- restoration, maintenance of sinus rhythm;

- relapse prevention;

- heart rate control.

Treatment of the paroxysmal form of atrial fibrillation involves the use of:

- "Novocainamide";

- "Cordarona";

- "Quinidine";

- "Propanorma".

Medicines are taken under constant monitoring of blood pressure and ECG. Also, for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, Anaprilin, Digoxin, and Verapamil can be prescribed. These medications provide a less pronounced effect, but also improve the patient's well-being and reduce the heart rate.

If drug treatment does not produce positive results, electrocardioversion is used. A pulsed electrical discharge is applied to the heart area, which stops the attack.

If the paroxysm lasts longer than 2 days, anticoagulant therapy for atrial fibrillation (Warfarin) is carried out to avoid the formation of blood clots. For preventive purposes, when sinus rhythm has already been restored, Propanorm, Cordarone Sotalex, etc. are used.

Treatment of permanent atrial fibrillation involves long-term use of:

- "Digoxin";

- adrenergic blockers (“Egilok”, “Atenolol”, “Concor”);

- "Warfarin";

- calcium antagonists (Verapamil, Diltiazem).

Surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation

Surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation is carried out if:

- antiarrhythmic therapy was ineffective;

- relapse prevention;

- During paroxysms, circulatory disturbances occur.

Most often, cardiologists use the following surgical treatment methods:

- Radiofrequency ablation of sources of atrial fibrillation. A special thin tube is passed through the femoral vessels to the heart. A radiofrequency pulse is sent through it, which eliminates possible sources of arrhythmia.

- Radiofrequency ablation of the atrioventricular node and installation of a pacemaker. The operation is performed if a chronic form of fibrillation is diagnosed and it is not possible to obtain a normal heart rate with the help of medications. This is a last resort. The radiofrequency pulse completely destroys the node responsible for transmitting the impulse from the atria to the ventricles. To ensure normal heart function, a pacemaker is installed, which supplies electrical impulses to the heart and creates a normal artificial rhythm.

- Installation of an atrial cardioverter-defibrillator. A cardioverter defibrillator is a device that is sewn under the skin in the upper chest. An electrode goes from it to the heart. The device blocks attacks of atrial fibrillation instantly by delivering electrical shocks.

- Open heart surgery. It is carried out if there are other serious heart diseases. At the same time, the sources of atrial fibrillation are affected in parallel.

Treatment of atrial fibrillation with folk remedies

Traditional medicine recipes can be used to normalize heart rate:

- Hawthorn tincture (sold in pharmacies). Take 20 drops 2-3 times a day.

- Infusion of viburnum fruits. 1 tbsp. l. pour a glass of boiling water over the viburnum fruit. Simmer over low heat for 5 minutes. Strain. Drink half a glass 2 times a day after meals.

- Infusion of dill seeds. Pour 1/2 teaspoon of seeds into a glass of boiling water. Leave for 30 minutes. Strain. Drink the resulting portion in three doses. You can add natural honey to the infusion.

Treatment of atrial fibrillation and flutter

What are the recommendations for antithrombotic therapy? How to choose a drug for preventive antiarrhythmic therapy?

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is one of the most common tachyarrhythmias in clinical practice, its prevalence in the general population ranges from 0.3 to 0.4% [1]. The detection of AF increases with age. Thus, among people under 60 years of age it is approximately 1% of cases, and in the age group over 80 years of age it is more than 6%. About 50% of patients with atrial fibrillation in the United States are over 70 years of age, and more than 30% of those hospitalized for cardiac arrhythmias are patients with this arrhythmia [2]. Atrial flutter (AFL) is a significantly less common arrhythmia compared to AF. In most countries, AF and AFL are considered different rhythm disorders and are not combined under the common term “atrial fibrillation.” In our opinion, this approach should be considered correct for many reasons.

Prevention of thromboembolic complications and relapses of atrial fibrillation and flutter

Atrial fibrillation and flutter worsen hemodynamics, aggravate the course of the underlying disease and lead to an increase in mortality by 1.5-2 times in patients with organic heart disease. Non-valvular (non-rheumatic) AF increases the risk of ischemic stroke by 2-7 times compared to the control group (patients without AF), and rheumatic mitral disease and chronic AF - by 15-17 times [3]. The incidence of ischemic stroke in non-rheumatic atrial fibrillation averages about 5% of cases per year and increases with age. Cerebral emboli recur in 30-70% of patients. The risk of another stroke is highest during the first year. The risk of stroke is low in patients with idiopathic AF under 60 years of age (1% per year), slightly higher (2% per year) at the age of 60-70 years. In this regard, most patients with frequent and/or prolonged paroxysms of atrial fibrillation, as well as its permanent form, should be prevented from thromboembolic complications. A meta-analysis of all studies on primary and secondary prevention of strokes showed that indirect anticoagulants reduce the risk of developing the latter by 47-79% (on average by 61%), and aspirin by a little more than 20%. It should be noted that when using aspirin, a statistically significant reduction in the incidence of ischemic stroke and other systemic embolisms is possible only with a fairly high dose of the drug (325 mg/day) [4]. At the same time, in the Copenhagen AFASAK Study [5], the number of thromboembolic complications in the groups of patients receiving aspirin 75 mg/day and placebo did not differ significantly.

In this regard, patients with AF who are at high risk for thromboembolic complications: heart failure, EF 35% or less, arterial hypertension, ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack in history, etc., should be prescribed indirect anticoagulants (maintaining the International Normalized ratio - INR - on average at the level of 2.0-3.0). For patients with non-valvular (non-rheumatic) atrial fibrillation who are not at high risk, continuous use of aspirin (325 mg/day) is advisable. There is an opinion that in patients under 60 years of age with idiopathic AF, in whom the risk of thromboembolic complications is very low (almost the same as in people without rhythm disturbances), preventive therapy may not be required. Antithrombotic therapy in patients with AFL should obviously be based on taking into account the same risk factors as in AF, since there is evidence that the risk of thromboembolic complications in AFL is higher than in sinus rhythm, but somewhat lower than in AF [ 6].

International experts offer the following specific recommendations for antithrombotic therapy for various groups of patients with atrial fibrillation, depending on the level of risk of thromboembolic complications [7]:

- age less than 60 years (no heart disease - lone AF) - aspirin 325 mg/day or no treatment;

- age less than 60 years (heart disease, but no risk factors such as congestive heart failure, EF 35% or less, arterial hypertension) - aspirin 325 mg/day;

- age 60 years or more (diabetes mellitus or coronary artery disease) - oral anticoagulants (INR 2.0-3.0);

- age 75 years or more (especially women) - oral anticoagulants (INR up to 2.0);

- heart failure - oral anticoagulants (INR 2.0-3.0);

- LVEF 35% or less - oral anticoagulants (INR 2.0-3.0);

- thyrotoxicosis - oral anticoagulants (INR 2.0-3.0);

- arterial hypertension - oral anticoagulants (INR 2.0-3.0);

- rheumatic heart defects (mitral stenosis) - oral anticoagulants (INR 2.5-3.5 or more);

- artificial heart valves - oral anticoagulants (INR 2.5-3.5 or more);

- history of thromboembolism - oral anticoagulants (INR 2.5-3.5 or more);

- the presence of a thrombus in the atrium, according to TPEchoCG, - oral anticoagulants (INR 2.5-3.5 or more).

The international normalized ratio should be monitored with indirect anticoagulants at the beginning of therapy at least once a week, and subsequently monthly.

In most cases, patients with recurrent paroxysmal and persistent atrial fibrillation in the absence of clinical symptoms of arrhythmia or their insignificant severity do not need to be prescribed antiarrhythmic drugs. In such patients, prophylaxis of thromboembolic complications (aspirin or indirect anticoagulants) and heart rate control are carried out. If clinical symptoms are pronounced, anti-relapse and relief therapy is required, combined with heart rate control and antithrombotic treatment.

In case of frequent attacks of atrial fibrillation and flutter, the effectiveness of antiarrhythmics or their combinations is assessed clinically; in case of rare attacks, TES or VEM is performed for this purpose after 3-5 days of taking the drug, and when using amiodarone - after saturation with it. To prevent relapses of AF/AFL in patients without organic heart disease, antiarrhythmic drugs of classes 1A, 1C and 3 are used. In patients with asymptomatic LV dysfunction or symptomatic heart failure, and possibly with significant myocardial hypertrophy, therapy with class 1 antiarrhythmics is contraindicated due to the risk of worsening life prognosis.

To prevent paroxysms of atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter, the following antiarrhythmics are used: quinidine (kinylentine, quinidine durules, etc.) - 750-1500 mg/day; disopyramide - 400-800 mg/day; propafenone - 450-900 mg/day; allapinin - 75-150 mg/day; etacizin - 150-200 mg/day; flecainide - 200-300 mg/day; amiodarone (maintenance dose) - 100-400 mg/day; sotalol - 160-320 mg/day; dofetilide - 500-1000 mcg/day. Verapamil, diltiazem and cardiac glycosides should not be used for anti-relapse therapy of AF and AFL in patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome (WPU), since these drugs reduce the refractoriness of the accessory atrioventricular conduction pathway and can cause aggravation of the arrhythmia.

In patients with sick sinus syndrome and paroxysms of atrial fibrillation and flutter (bradycardia-tachycardia syndrome), there are expanded indications for implantation of an electrical pacemaker (pacemaker). Permanent pacing is indicated in such patients both for the treatment of symptomatic bradyarrhythmia and for the safe administration of preventive and/or curative antiarrhythmic therapy. To prevent and relieve attacks of AF and AFL in patients without pacemakers, class 1A antiarrhythmics with anticholinergic effects (disopyramide, procainamide, quinidine) can be used. In hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, amiodarone is prescribed to prevent tachyarrhythmia paroxysms, and beta-blockers or calcium antagonists (verapamil, diltiazem) are prescribed to reduce the frequency of ventricular contractions.

As a rule, treatment with antiarrhythmics requires monitoring the width of the QRS complex (especially when class 1C antiarrhythmics are used) and the duration of the QT interval (when treated with class 1A and 3 antiarrhythmics). The width of the QRS complex should not increase by more than 150% of the initial level, and the corrected QT interval should not exceed 500 ms. Amiodarone has the greatest effect in preventing arrhythmia [14, 15, 16, 17]. A meta-analysis of published results from placebo-controlled studies involving 1465 patients showed that the use of low maintenance doses of amiodarone (less than 400 mg/day) did not cause an increase in lung and liver damage compared with the placebo group [8]. Some clinical studies have demonstrated a higher preventive effectiveness of class 1C drugs (propafenone, flecainide) compared to class 1A antiarrhythmics (quinidine, disopyramide). According to our data, the effectiveness of propafenone is 65%, ethacyzine - 61% [9, 10].

Choice of drug for prophylactic antiarrhythmic therapy of paroxysmal and persistent atrial fibrillation and flutter

We can agree with the opinion expressed in international recommendations for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation [7], according to which anti-relapse therapy in patients without heart pathology or with minimal structural changes should begin with class 1C antiarrhythmics (propafenone, flecainide). Let's add to them domestic drugs of the same class (allapinin and etacizin), as well as sotalol; they are quite effective and devoid of pronounced extracardiac side effects. If the listed antiarrhythmics do not prevent relapses of AF/AFL or their use is accompanied by side effects, you should proceed to prescribing amiodarone and dofetilide. Then, if necessary, class 1A drugs (disopyramide, quinidine) or non-pharmacological treatments are used. Probably, in patients with so-called “adrenergic” AF, one can expect a greater effect from therapy with amiodarone or sotalol, and in “vagal” AF it is advisable to start treatment with disopyramide.

Coronary heart disease, especially in the presence of post-infarction cardiosclerosis, and heart failure increase the risk of manifestation of the arrhythmogenic properties of antiarrhythmic drugs. Therefore, treatment of atrial fibrillation and flutter in patients with congestive heart failure is usually limited to the use of amiodarone and dofetilide. While the high efficacy and safety of amiodarone in heart failure and coronary artery disease (including myocardial infarction) has been proven for a long time, similar results for dofetilide were obtained in the recent placebo-controlled studies DIAMOND CHF and DIAMOND MI [11].

For patients with coronary heart disease, the recommended sequence of prescribing antiarrhythmics is as follows: sotalol; amiodarone, dofetilide; disopyramide, procainamide, quinidine.

Arterial hypertension, leading to hypertrophy of the left ventricular myocardium, increases the risk of developing polymorphic ventricular tachycardia “torsades de pointes”. In this regard, to prevent relapses of AF/AFL in patients with high blood pressure, preference is given to antiarrhythmic drugs that do not significantly affect the duration of repolarization and the QT interval (class 1C), as well as amiodarone, although it prolongs it, but extremely rarely causes ventricular tachycardia . Thus, the algorithm for pharmacotherapy of this rhythm disorder in arterial hypertension appears to be as follows: LV myocardial hypertrophy of 1.4 cm or more - use only amiodarone; There is no left ventricular myocardial hypertrophy or it is less than 1.4 cm - start treatment with propafenone, flecainide (bear in mind the possibility of using domestic class 1C antiarrhythmics allapinin and etacizin), and if they are ineffective, use amiodarone, dofetilide, sotalol. At the next stage of treatment (ineffectiveness or occurrence of side effects of the above drugs), disopyramide, procainamide, and quinidine are prescribed [7].

It is quite possible that with the emergence of new results from controlled studies on the effectiveness and safety of antiarrhythmic drugs in patients with various diseases of the cardiovascular system, changes will be made to the above recommendations for the prevention of relapses of paroxysmal and persistent AF, since at present the relevant information is clearly insufficient.

If there is no effect from monotherapy, combinations of antiarrhythmic drugs are used, starting with half doses. An addition, and in some cases an alternative to preventive therapy, as mentioned above, may be the prescription of drugs that worsen AV conduction and reduce the frequency of ventricular contractions during paroxysms of AF/AFL. The use of drugs that impair conduction in the AV junction is justified even in the absence of effect from preventive antiarrhythmic therapy. When using them, it is necessary to ensure that the heart rate at rest is from 60 to 80 per minute, and with moderate physical activity - no more than 100-110 per minute. Cardiac glycosides are ineffective for controlling heart rate in patients leading an active lifestyle, since in such cases the primary mechanism for reducing the frequency of ventricular contractions is an increase in parasympathetic tone. Therefore, it is obvious that cardiac glycosides can be chosen only in two clinical situations: if the patient suffers from heart failure or has low physical activity. In all other cases, preference should be given to calcium antagonists (verapamil, diltiazem) or beta-blockers. In case of prolonged attacks of atrial fibrillation or flutter, as well as in their permanent form, combinations of the above drugs can be used to reduce heart rate.

Relief of paroxysms of fibrillation and atrial flutter

The primary task during an attack of the tachysystolic form of AF/AFL is to reduce the heart rate, and then, if the paroxysm does not stop on its own, stop it. Control of the ventricular contraction rate (decrease to 70-90 per minute) is carried out by intravenous administration or oral administration of verapamil, diltiazem, beta-blockers, intravenous administration of cardiac glycosides (preference is given to digoxin), amiodarone. In patients with reduced LV contractile function (congestive heart failure or EF less than 40%), heart rate is reduced only with cardiac glycosides or amiodarone. Before stopping tachysystolic forms of atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter (especially atrial flutter) with class 1A antiarrhythmics (disopyramide, procainamide, quinidine), conduction blockade in the AV node is required, since the above-mentioned antiarrhythmic drugs have an anticholinergic effect (most pronounced with disopyramide) and can significantly increase the frequency contractions of the ventricles.

Considering the risk of thromboembolism during prolonged paroxysm of AF, the issue of stopping it must be resolved within 48 hours, since if the duration of an attack of AF exceeds two days, it is necessary to prescribe indirect anticoagulants (maintaining the INR at the level of 2.0-3.0) for 3-4 weeks before and after electrical or drug cardioversion. Currently, the most widely used indirect anticoagulants are coumarin derivatives: warfarin and syncumar. If the duration of AF is unknown, the use of indirect anticoagulants before and after cardioversion is also necessary. Similar prevention of thromboembolic complications should be carried out in case of atrial flutter.

For pharmacological cardioversion, the following antiarrhythmics are used:

- amiodarone 5-7 mg/kg - intravenous infusion over 30-60 minutes (15 mg/min);

- ibutilide 1 mg - intravenous administration over 10 minutes (if necessary, repeated administration of 1 mg);

- novocainamide 1-1.5 g (up to 15-17 mg/kg) - intravenous infusion at a rate of 30-50 mg/min;

- propafenone 1.5-2 mg/kg - intravenous administration over 10-20 minutes;

- flecainide 1.5-3 mg/kg - intravenous administration over 10-20 minutes.

The international recommendations for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiac care [12] and the ACC/AHA/ECC recommendations for the treatment of patients with atrial fibrillation [7] note that it is advisable to relieve paroxysm in patients with heart failure or EF less than 40% mainly with amiodarone. The use of other antiarrhythmics should be limited due to the rather high risk of developing arrhythmogenic effects and the negative impact of these drugs on hemodynamics.

The use of verapamil and cardiac glycosides is contraindicated in patients with AF/AFL and Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. In the presence of the latter, AF/AFL is treated with drugs that impair conduction along the Kent bundle: amiodarone, procainamide, propafenone, flecainide, etc.

Oral relief of atrial fibrillation and flutter with quinidine, procainamide, propafenone, flecainide, dofetilide, etc. is possible.

Atrial flutter (type 1) can be relieved or converted to AF by frequent transesophageal or endocardial atrial pacemaker. Stimulation is prescribed for a duration of 10-30 seconds with a pulse frequency that is 15-20% higher than the frequency of atrial contractions, i.e. 300-350 (400) pulses per minute.

When AF/AFL is accompanied by severe heart failure (cardiac asthma, pulmonary edema), hypotension (systolic pressure less than 90 mm Hg), increased pain and/or worsening myocardial ischemia, immediate electrical pulse therapy (EPT) is indicated.

In case of atrial fibrillation, EIT begins with a discharge with a power of 200 J; for biphasic current, the energy of the first discharge is less. If it turns out to be ineffective, discharges of higher power (300-360 J) are successively applied. Atrial flutter is often relieved by a low-energy shock (50-100 J).

Electropulse therapy can also be chosen for the planned restoration of sinus rhythm in patients with prolonged paroxysms of AF/AFL. Medical cardioversion is recommended if EIT is not possible, undesirable, or fails to restore sinus rhythm. In case of an attack of AF/AFL lasting more than 48 hours, indirect anticoagulants before cardioversion can not be used for a long time if transesophageal echocardiography (TPEchocardiography) excludes the presence of thrombi in the atria (in 95% of cases they are localized in the left atrial appendage). This is the so-called early cardioversion: intravenous administration of heparin (increase in aPTT by 1.5-2 times compared to the control value) or short-term administration of an indirect anticoagulant (bringing the INR to 2.0-3.0) before cardioversion and four weeks of indirect administration anticoagulants after restoration of sinus rhythm. According to preliminary data from the ACUTE multicentre study [13], the incidence of thromboembolic complications is significantly lower when using TPEchoCG and short courses of preventive therapy with heparin or warfarin (in the absence of a thrombus) or longer-term administration of an indirect anticoagulant (if a thrombus is re-detected after three weeks of warfarin treatment) before EIT, than with traditional therapy carried out “blindly” with indirect anticoagulants for 3-4 weeks before and after electrical cardioversion, and is 1.2% and 2.9%, respectively. In patients who do not receive anticoagulants before cardioversion, thromboembolic complications develop in 1-6% of cases.

For severe paroxysms of AF and AFL, refractory to drug treatment, non-pharmacological treatment methods are used: destruction of the AV connection with implantation of an electrical pacemaker, “modification” of the AV connection, implantation of an atrial defibrillator or special pacemakers, radiofrequency catheter destruction of the impulse circulation path in the right atrium during AFL and sources ectopic impulses in patients with focal atrial fibrillation, “corridor” and “labyrinth” operations.

Literature

1. Kastor JA Arrhithmias. Philadelphia: WB Saunders company 1994. P.25-124. 2. Bialy D., Lehmann MN, Schumacher DN et al. Hospitalization for arrhythmias in the United States: importance of atrial fibrillation (abstr) // J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1992; 19:41A. 3. Wolf PA, Dawber TR, Thomas HE, Kannel WB Epidemiologic assessment of chronic atrial fibrillation and risk of stroke: the Framingham study // Neurology. 1978; 28: 973-77. 4. The Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Study Group Investigators. Stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation study: final results//Circulation. 1991; 84:527-539. 5. Petersen P., Boysen G., Godtfredsen J. et al. Placebo-controlled, randomized trial of warfarin and aspirin for prevention of thromboembolic complications in chronic atrial fibrillation. The Copenhagen AFASAK study // Lancet. 1989; 1: 175-179. 6. Biblo LA, Ynan Z, Quan KJ et al. Risk of stroke in patients with atrial flutter // Am. J. Cardiol. 2000; 87: 346-349. 7. ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines for management of patients with atrial fibrillation//Circulation. 2001; 104: 2118-2150. 8. Vorperian VR, Havighurst TC, Miller S., Janyary CT Adverse effect of low dose amiodarone: a meta-analysis // JACC. 1997; 30: 791-798. 9. Bunin Yu. A., Fedyakina L. F., Bayroshevsky P. A., Kazankov Yu. N. Combined preventive antiarrhythmic therapy with etatsizin and propranolol for paroxysmal fibrillation and atrial flutter. Materials of the VII Russian National Congress “Man and Medicine”. Moscow, 2000. P. 124. 10. Semykin V.N., Bunin Yu.A., Fedyakina L.F. Comparative effectiveness of combined antiarrhythmic therapy with propafenone, verapamil and diltiazem for paroxysmal fibrillation and atrial flutter. Materials of the VII Russian National Congress “Man and Medicine”. Moscow, 2000. pp. 123-124. 11. Sager PT New advances in class III antiarrhytmic drug therapy. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2000; 15: 41-53. 12. Guidelines 2000 for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care // Circulation. 2000; 102 (suppl I): I-158-165. 13. Design of a clinical trial for the assessment of cardiversion using transesophageal echocardiography (the ACUTE multicenter study) // Am. J. Cardiol. 1998; 81: 877-883. 14. Bunin Yu. A., Firstova M. I., Enukashvili R. R. Maintenance antiarrhythmic therapy after restoration of sinus rhythm in patients with a permanent form of atrial fibrillation. Materials of the 5th All-Russian Congress of Cardiologists. Chelyabinsk, 1996. P. 28. 15. Bunin Y., Fediakina L. Low doses of amiodarone in preventing of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation and flutter. International academy of cardiology. 2nd international congress on heart disease. Abstract book of the congress, Washington, USA, 2001. 16. Gold RL, Haffajec CI Charoz G. et al. Amiodarone for refractory atrial fibrillation // Am. J. Cardiol. 1986; 57: 124-127. 17. Miller JM, Zipes DP Management of the patient with cardiac arrhythmias. In Braunwald E., Zipes D., Libby P. (eds). Heart disease. A textbook of cardiovascular medicine. Philadelphia: WB Saunders company. 2001. P. 731-736.

Diet

With atrial fibrillation, the patient should eat foods rich in vitamins, microelements and substances that can break down fats. This means:

- garlic, onion;

- citrus;

- honey;

- cranberry, viburnum;

- cashews, walnuts, peanuts, almonds;

- dried fruits;

- dairy products;

- sprouted wheat grains;

- vegetable oils.

The following should be excluded from the diet:

- chocolate, coffee;

- alcohol;

- fatty meat, lard;

- flour dishes;

- smoked meats;

- canned food;

- rich meat broths.

Apple cider vinegar helps prevent blood clots from forming. 2 tsp. You need to dilute it in a glass of warm water and add a spoonful of honey. Drink half an hour before meals. The preventive course is 3 weeks.

Prevention

Primary prevention of atrial fibrillation involves proper treatment of heart failure and arterial hypertension. Secondary prevention consists of:

- compliance with medical recommendations;

- conducting cardiac surgery;

- limiting mental and physical stress;

- giving up alcoholic drinks and smoking.

The patient must also:

- eat rationally;

- control body weight;

- monitor blood sugar levels;

- do not take medications uncontrollably;

- measure blood pressure daily;

- treat hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism.

This article is posted for educational purposes only and does not constitute scientific material or professional medical advice.