- Gallery

- Reviews

- Articles

- Licenses

- Vacancies

- Insurance partners

- Partners

- Controlling organizations

- Schedule for receiving citizens for personal requests

- Online consultation with a doctor

- Documentation

Pancreatitis is inflammation of the pancreas. There are 2 main forms of this inflammation: acute and chronic. These forms are more common in adults.

In recent years, it has become common to identify another one - reactive pancreatitis (correctly called reactive pancreatopathy) - which is more common in children.

When the pancreas becomes inflamed, the enzymes secreted by the gland are not released into the duodenum, but begin to destroy it (self-digestion). The enzymes and toxins that are released often enter the bloodstream and can seriously damage other organs: the brain, lungs, heart, kidneys and liver.

In 97% of cases, the main cause of pancreatitis is:

- poor nutrition;

- monotonous food;

- regular overeating;

- acute poisoning;

- preference for fried, fatty, spicy foods and fast food instead of healthy foods.

Pancreatitis has the same symptoms regardless of the form of the disease: chronic or acute. The main symptom of the disease is acute pain in the abdominal area.

About the disease

Pancreatitis is a common pathology of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT), which is accompanied by local inflammation of the pancreatic tissue and its ducts.

The organ in question plays a key role in the digestion process, ensuring the release of large amounts of enzymes into the intestines. The pancreas is also involved in controlling blood glucose levels through the secretion of insulin. Pancreatitis leads to disruption of these functions, which can cause a serious deterioration in the child’s condition. The disease occurs acutely or chronically. In children, it is important to recognize the pathology as quickly as possible in order to prescribe adequate treatment in a timely manner. Otherwise, the disease progresses and leads to organic damage to the gland tissue and an increased risk of developing serious complications - diabetes mellitus, severe digestive disorders, collapsed reactions (fainting and loss of consciousness).

Acute pancreatitis: treatment and first aid

When initial symptoms of the disease appear, you must call an ambulance. Treatment of acute pancreatitis takes place exclusively in a hospital setting under the constant supervision of specialists.

While waiting for doctors, to alleviate the patient’s condition, you can put cold on his stomach. As for medications, you can take any antispasmodics - papaverine, no-shpu, smazmalgon, etc. From the moment the first symptoms appear, you should stop any food intake (including juices) and go to bed. Doctors say that no medicine treats pancreatitis better than cold, hunger and rest.

Treatment in a hospital is carried out taking into account the clinic. Antispasmodics, prokinetics, anti-inflammatory drugs, antisecretory, antibacterial drugs are used (for the prevention or treatment of bacterial complications). Treatment is carried out by infusion (through a dropper). Diet therapy (when the patient is allowed to resume eating) is of great importance. Enzyme preparations are used during meals.

Symptoms of pancreatitis

Pancreatitis is a disease that in 90% of cases is accompanied by a violation of the secretion of digestive enzymes by the gland. The result of such a lesion is a deterioration in the functioning of the child’s gastrointestinal tract with the appearance of characteristic symptoms. The most common signs of pancreatitis in children are:

- pain in the abdomen - the discomfort is girdling in nature and radiates to the back;

- flatulence;

- violation of bowel movements such as diarrhea;

- loss of appetite;

- nausea, vomiting;

- increase in body temperature to 37-38°C.

In infants and newborns, the symptoms of pancreatitis are less severe than in children of the older age group.

Sometimes parents may not even notice any special changes in the baby’s behavior. In adolescents, the symptoms of the disease differ in brightness and intensity. This is due to the influence of a significant number of provoking factors. The clinical picture of the disease depends on the form and duration of the pathological process, as well as the degree of damage to the pancreas. With chronic inflammation, the pain can be of a protracted, aching nature. At the same time, the child loses body weight, the condition of the skin, nails, and hair worsens.

If any of these signs are detected, parents should seek help from a doctor. Early diagnosis of pancreatitis with the prescription of adequate treatment helps to quickly stabilize the baby’s digestive function and minimize the risk of complications.

Reactive pancreatitis

Reactive pancreatitis is caused by spasms of the pancreatic ducts, as a result of which enzymes cannot enter the gastrointestinal tract and accumulate in the gland, beginning to “digest” it. The child begins to experience pain, which usually manifests itself sharply and sharply, is clearly localized above the navel and is girdling in nature. Nausea and vomiting of undigested stomach contents are possible. The attack of pain can last up to several hours.

An attack of reactive pancreatitis can be caused by:

- inflammatory processes in the child’s body (with acute respiratory viral infections, influenza, sore throat, diseases of the gastrointestinal tract);

- excessive consumption of food that the child’s body is not able to cope with. First of all, these are fried foods, dry foods (chips, crackers with seasonings), carbonated drinks;

- food with a large number of preservatives, flavor enhancers and other food additives;

- change of diet (for example, when a child enters school or kindergarten). This is how the body reacts to unusual food;

- taking certain medications (antibiotics or antiviral drugs).

Causes of pancreatitis

The pathogenetic basis of pancreatitis of any origin is local inflammation of the gland tissue.

The key mechanism of this pathological process is the release of excessive amounts of active enzymes, which begin to damage the organ's own structures. Hyperactivation of the secretory function of the gland can be either primary or secondary (develops as a result of pathology of other organs and systems). In newborns and infants, pancreatitis most often occurs as a result of congenital anomalies in the development of the organ and its ducts. Due to the lack of adequate outflow, enzymes accumulate inside the gland and trigger the process of lysis (chemical destruction) of its own tissues.

In school-age children and teenagers, activation of the secretion of bioactive enzymes can be triggered by the following factors:

- eating large amounts of fried and fatty foods - the child’s digestive tract is not suitable for digesting “heavy” foods;

- viral or bacterial lesions of the gastrointestinal tract with penetration of the pathogen into the pancreas;

- narrowing of pancreatic ductuses against the background of neoplastic processes in the abdominal cavity.

The risk of developing pancreatitis also increases with irregular nutrition, consumption of large amounts of fast food, and carbonated drinks. Damage to the pancreas sometimes occurs due to the use of aggressive medications or the entry of toxins into the baby’s gastrointestinal tract.

Pancreatitis in children

The problem of pancreatitis in childhood is not new today, but remains, perhaps, the least studied page in pediatric gastroenterology. Its active study began after the introduction of ultrasound into everyday practice, which suggested a relatively high frequency of pancreatitis, including chronic pancreatitis, in the structure of diseases of the digestive organs in children. In the 60–80s. last century, these issues were intensively studied in our country and, perhaps, much more intensively than abroad. In the domestic pediatric literature one can find many articles devoted to pancreatitis in children. These studies were headed by A.V. Mazurin, A.M. Zaprudnoy, I.V. Dvoryakovsky, N.G. Zernov, B.G. Apostolov, G.V. Rimarchuk, Zh.P. Gudzenko. In 1980, Zh. P. Gudzenko’s book “Pancreatitis in Children” was published, which remained the only monograph devoted to this topic. Currently, research into the problem of pancreatitis in childhood continues both in our country and abroad. A special message for the development of this direction was given by the isolation and genetic identification of the so-called. hereditary pancreatitis. However, many questions, both theoretical and directly practical, remain unresolved. In numerous gastroenterology forums, this problem has received relatively little attention, not due to lack of relevance, but due to the lack of tangible progress.

The frequency of pancreatitis in children with diseases of the digestive system, according to various authors, ranges from 5 to 25%. Such a significant scatter is associated both with diagnostic difficulties and with the lack of a clear terminological definition of the subject of study. In everyday practice, there are usually four diagnoses that somehow fit into the topic of this discussion: acute pancreatitis, chronic recurrent pancreatitis, chronic latent pancreatitis, reactive pancreatitis (and/or secondary pancreatitis). The first two diseases are quite unambiguous from a diagnostic and terminological point of view, and their frequency can be reliably determined.

As for chronic latent pancreatitis, its diagnosis is very difficult due to the lack of criteria available for everyday use. The basis for such a diagnosis is usually the identification of compaction of the pancreatic parenchyma (PG) and/or its heterogeneity during ultrasound examination and the absence of corresponding clinical symptoms. However, whether these signs correspond to chronic pancreatitis in all cases is a question that is quite difficult to answer. The widespread introduction of ultrasound into clinical pediatric practice has revealed a fairly large number of such findings. This was a cause for concern, since it indicated a high incidence of chronic latent pancreatitis in children, and also gave reason to doubt the diagnostic significance of such an interpretation of the results due to possible overdiagnosis. The question of reactive pancreatitis causes even more controversy.

Pancreatitis is based on a destructive process in the pancreas, accompanied by microcirculatory disorders (which often precede the destruction itself), an inflammatory process and, to a greater or lesser extent, fibrosis. Against the background of the latter, exocrine and/or endocrine insufficiency of the pancreas can form. To be fair, it should be noted that pancreatic insufficiency with pancreatitis in children develops relatively rarely. The active destructive process in the pancreas is accompanied by the phenomenon of “evasion of pancreatic enzymes into the blood,” an increase in their concentration in the blood due to the destruction of acinar cells and increased permeability of the barrier between the acini and the blood. This phenomenon allows one to reliably identify destruction in the pancreas and diagnose acute pancreatitis or exacerbation of chronic recurrent pancreatitis.

In light of the presented general scheme, acute pancreatitis (as well as exacerbation of chronic) is an active destructive process in the pancreas tissue. Chronic pancreatitis is characterized by fibrosis of the pancreas, against the background of which, from time to time, under the influence of various provoking factors, destructive processes develop, i.e., exacerbations occur. Chronic latent pancreatitis theoretically has the right to exist as fibrosis of the pancreas, also associated with periodic episodes of destruction, which has not manifested itself as documented exacerbations. It is assumed that the destruction of the pancreas in this case occurs gradually, which leads to the absence of a typical clinical picture and the appearance of primary chronic latent pancreatitis. This concept is logical, but we judge the frequency of this condition only from ultrasound data. Computed tomography (not to mention biopsy), which could give us more reliable information, cannot be used on a mass scale for this purpose. There are no other signs of latent pancreatitis and cannot be by definition (aka latent!). This circumstance constitutes the first serious problem facing pediatric gastroenterologists. Moreover, it also applies to the diagnosis of chronic recurrent pancreatitis without exacerbation. And it is precisely because of this that we do not have accurate statistics on pancreatitis in children.

The second question is reactive pancreatitis. This concept often hides two states, sometimes different and sometimes coinciding. Firstly, we can talk about secondary pancreatitis, which was a consequence of any disease, including the digestive organs. Secondly, we can talk about a condition that precedes the destruction of pancreatic tissue in the form of its edema, which is revealed by ultrasound in the form of an increase in the size of one or more parts of the organ and corresponding changes in its parenchyma. This condition is most often secondary, and the term “reactive” in this case is quite appropriate, but it is not actually “pancreatitis”. In addition, this condition is reversible provided that the underlying disease is treated and, perhaps, some auxiliary therapy aimed at improving microcirculation. The appearance of signs of cytolysis, i.e. hyperenzymemia, clearly indicates acute pancreatitis or exacerbation of chronic pancreatitis, and in this case additional terminology is no longer required. Thus, it is necessary to decide whether by the term “reactive pancreatitis” we mean secondary pancreatitis (precisely pancreatitis) or do we mean a reactive state of the pancreas without destruction (which most often occurs in practice), when the term “dyspancreatism” may be more appropriate " However, these issues should be resolved centrally in forums of pediatric gastroenterologists and continue to be spoken “in the same language.” The importance of this problem is determined by the prognosis of the development of this condition, which in some patients will be reversible with adequate treatment of the underlying disease, but in some of them “true” pancreatitis may develop. The mechanism of this process is most likely associated with prolonged ischemia of pancreatic tissue against the background of microcirculatory disorders.

Leaving terminological disputes aside, it should be recognized that pancreatitis, including chronic pancreatitis, is a reality in pediatric practice. The latter (like any chronic process) can have a recurrent or latent course, which is a general pathological pattern.

Also, pediatricians quite often encounter a reactive state of the pancreas, which can evolve both towards restoring the state of the organ and along the path of its destruction.

The reasons for the development of pancreatitis in children are numerous and can be combined into several groups.

- Violation of the outflow of pancreatic secretions:

- anomalies of the pancreatic ducts, anomalies of the pancreas, compression of the ducts from the outside, obstruction with stones;

- pathology of the duodenum (observed in approximately 40% of patients), increased intraduodenal pressure of various origins;

- pathology of the biliary tract (observed in approximately 40% of patients).

- Increased (absolute or relative) activity of pancreatic enzymes in pancreatic tissue:

- excessive stimulation of the pancreas, primarily determined by the nature of nutrition;

- hereditary pancreatitis (premature activation of enzymes).

- Infectious factor:

- mumps virus, hepatitis viruses, enteroviruses, cytomegaloviruses, herpes viruses, mycoplasma infections, salmonellosis, infectious mononucleosis and many others. etc.

This group also includes the development of pancreatitis due to helminthiasis (opisthorchiasis, strongyloidiasis, ascariasis, etc.), as well as pancreatitis due to sepsis.

- Pancreatic injury.

- System processes:

- connective tissue diseases;

- endocrine pathology;

- hyperlipidemia;

- hypothyroidism;

- hyperparathyroidism;

- hypercalcemia of various origins;

- chronic renal failure;

- cystic fibrosis.

The last disease is, of course, special in the above list. Fibrosis in cystic fibrosis is associated to a large extent with the characteristics of fibroblast function and is of a congenital (genetic) nature, although the factor of impaired outflow from the pancreas is also important. Whether the processes occurring in the pancreas during cystic fibrosis can be regarded as pancreatitis is a controversial issue and requires separate discussion.

- Microcirculation disorders, including systemic ones:

- allergic diseases, consumption of foods containing xenobiotics, as well as secondary conditions in diseases of the digestive system and many others.

This group in pediatric practice is very numerous, especially when it comes to the so-called. reactive pancreatitis.

- Toxic effects of certain drugs:

- corticosteroids, sulfonamides, cytostatics, furosemide, metronidazole, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, etc.

Pancreatitis of hereditary origin deserves special attention. Described in 1952 by Comfort and Steiberg, it has in recent years become the object of close study throughout the world. Currently, several mutations of several genes responsible for the development of this disease have been identified. In one of the variants of hereditary pancreatitis, the disease is transmitted in an autosomal dominant manner with 80% penetrance. In 1996, the gene responsible for its development, encoding cationic trypsinogen, was identified on chromosome 7 q35. To date, 8 mutations in this gene have been described. Mutations D22G, K23R, N29I, N29T, R122H and R122C lead to increased autoactivation of trypsinogen, mutations N29T, R122H and R122C stabilize trypsin in relation to its inhibitors, while mutations D22G, K23R and N29I are not associated with any known effect . The R122H mutation removes the autolysis point Arg122, the D22G and K23R mutations suppress activation by cathepsin B. In all cases of these mutations, the balance between proteases and antiproteases is disrupted with an increase in intracellular protease activity and cell destruction. Hereditary pancreatitis manifests itself from the first years of life, and in older age, the presence of these mutations is associated with a 50-fold increase in the risk of developing pancreatic cancer. In addition to changes in the trypsinogen gene, mutations in the trypsin inhibitor gene (Serin Protease Inhibitor Kazal type 1 = SPINK1 or PSTI) on chromosome 5, and in the cystic fibrosis gene on chromosome 7 may also be responsible for the development of pancreatitis. In these cases, an autosomal recessive mode of inheritance is assumed.

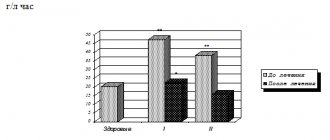

Secondary dysfunction of the pancreas is observed in many conditions, including intestinal malabsorption syndrome. Thus, with celiac disease and lactase deficiency (LD), it is possible to identify varying degrees of severity of involvement of the pancreas in the pathological process. According to our data, with celiac disease in the active stage of the disease, pancreatic damage is observed in 88% of patients, in the remission stage - in 79%, and with LN - in 76%. An increase in trypsin activity in the blood, indicating a destructive process in the pancreas, is observed in 37% of children in the active stage of celiac disease and in 12% of patients in remission. In LN, high trypsinogenemia was observed only in 7% of patients. As for the increased excretion of triglycerides in feces, indicating exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, we found the opposite picture: a low frequency in the active stage (18%) and a higher frequency in the remission stage (52%). In LN, moderate steatorrhea due to triglycerides was observed in 38% of children. The identified pattern coincided with that when assessing the frequency of detection of signs of chronic pancreatitis according to ultrasound data. Signs of chronic pancreatitis were not detected in the active stage of celiac disease, but were found in 58% of patients with celiac disease in remission and in 32% of sick children with LI. One can assume the gradual formation of chronic pancreatitis as the process progresses, even against the background of persistent remission of celiac disease with a decrease in exocrine pancreatic function.

The mechanisms of pancreatic damage in celiac disease are directly related to the atrophic process in the small intestine. This atrophy is hyperregenerative in nature, which is manifested by significant deepening of the crypts and increased mitotic activity in them. Along with the increase in the number of enterocytes themselves, the number of somatostatin-producing D-cells in the crypts also increases in the active stage of celiac disease with their normalization in the remission stage. Hyperplasia of D-cells is accompanied by an increase in the production of somatostatin and, as a consequence, suppression of the activity of I-cells producing cholecystokinin and S-cells producing secretin, which leads to a decrease in the function of acinar cells of the pancreas.

Another mechanism of damage to the pancreas in celiac disease is associated with a violation of its trophism and, apparently, has more long-term consequences. Severe malnutrition, regardless of the cause, is characterized by dysfunction of all organs, including the digestive glands.

Trophic disturbances and a decrease in the stability of cell membranes, of course, contribute to the development of cytolysis of acinar cells of the pancreas, which are quite sensitive to various unfavorable factors. Destruction is manifested by pancreatic hyperfermentemia and is an essentially implicit reflection (without clear clinical manifestations) of acute pancreatitis or exacerbation of chronic pancreatitis in a patient with celiac disease. In the pathogenesis of these disorders, an autoimmune mechanism cannot be excluded, since it is known that autoantibodies to various organs, including pancreatic cells, appear in the blood in celiac disease, although autoaggression against acinar cells remains unproven. Ischemia of pancreatic tissue, which persists for a long time, can be the cause of sluggish pancreatitis with its chronicity in the future. And although in the remission stage of celiac disease, intestinal absorption and nutritional status are restored, the number of somatostatin-producing cells is normalized, and the level of a number of trophic factors even increases, the damage caused to the pancreas in the active stage remains not always reparable. This is manifested by a high frequency of chronic pancreatitis with exocrine pancreatic insufficiency against the background of well-being in the underlying disease.

Changes in the pancreas with lactase deficiency are milder and transient in nature, however, the possibility of developing chronic pancreatitis in this group of children should also be taken into account by doctors when drawing up an examination and treatment plan.

Food allergies are also often accompanied by damage to the pancreas. According to our data, the frequency of pancreatic hyperenzymemia, which indicates the possibility of pancreatitis, with food allergies in children is observed in approximately 40% of cases, and the frequency of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency of varying severity according to the results of indirect tests (stool lipid profile) approaches 60%. In this case, the frequency of damage correlates with the age of the patient or, essentially, with the duration of the disease. Damage to the pancreas in food allergies is associated with the release of a significant amount of vasoactive mediators with the development, on the one hand, of direct damage to the parenchyma and, on the other hand, disruption of microcirculation in the organ, its ischemia, secondary damage and subsequent sclerosis. The presented mechanisms demonstrate the possibility of development of both acute and chronic processes. True acute pancreatitis with food allergies in children rarely develops, and only isolated cases have been described. Most often, chronic pancreatitis gradually develops, which can manifest itself as exocrine pancreatic insufficiency. At the same time, disruption of the digestion processes contributes to allergies, since it increases the antigenic load in various ways. Thus, allergy and pancreatic damage mutually support each other, which is confirmed by the high frequency of allergies in chronic pancreatitis of other origins.

Diagnosis of pancreatitis, as mentioned above, is difficult when it comes to chronic pancreatitis without exacerbation. Acute pancreatitis and exacerbation of chronic pancreatitis are characterized by a clinical picture in which, as a rule, there are abdominal pain, vomiting, and a general serious condition with symptoms of intoxication. In typical cases, the pain is intense, localized in the paraumbilical area with irradiation to the back or has a girdling nature, however, pain symptoms in children are often blurred without a distinct localization. Vomiting, repeated in typical cases, may be single or even absent. A characteristic laboratory marker of this condition is hyperenzymemia with an increase in the activity of amylase, lipase, trypsin, elastase 1 and a number of other enzymes in the blood. It should be noted that amylase has a low diagnostic value. More informative are the levels of lipase and trypsin activity in the blood. Determination of elastase 1 in the blood is considered an accurate marker of pancreatic tissue destruction, but its determination in our country is carried out only in some laboratories.

Ultrasound examination of the pancreas shows an increase in the size of the organ and signs of edema. As the severity of the process subsides, the size of the pancreas decreases and signs become apparent, usually interpreted as sclerotic changes characteristic of chronic pancreatitis, in the form of compaction and heterogeneity of the parenchyma.

Exocrine pancreatic secretion during pancreatitis in children suffers relatively little, but its assessment can help in the diagnostic process and is of great importance for developing patient management tactics, especially in the remission stage.

To assess exocrine pancreatic secretion in everyday practice, well-known methods such as coprogram and fecal lipidogram, as well as relatively new ones, including determination of elastase 1 activity in stool, which in recent years have become the modern “gold standard” for assessing pancreatic function, can be used. Pancreatic elastase 1 reaches the distal intestine unchanged and is determined by enzyme immunoassay using monoclonal antibodies (Elastase 1 stool test). The method was shown to be highly informative, which in this regard is comparable to the pancreozymin test. At the same time, the determination of elastase 1 in feces is much cheaper and easier to carry out. The norm is considered to be elastase 1 values in feces above 200 mcg/ml feces. Lower values indicate pancreatic insufficiency. It is important that the test results are not affected by the patient’s diet or the use of pancreatic enzyme medications.

On the other hand, this method does not allow assessing the severity of the relatively common relative pancreatic insufficiency, while showing normal values of fecal elastase 1. Only by comparing these data with the results of indirect tests (coprograms or stool lipidograms) can we draw a conclusion about the secondary nature of digestive insufficiency. The only exception is primary lipase deficiency, in which, against the background of severe steatorrhea due to triglycerides, a normal value of fecal elastase 1 will be observed.

Finally, only data from indirect methods of studying the exocrine function of the pancreas make it possible to assess the adequacy of replacement therapy and select the dose of the drug.

Treatment of exacerbation of chronic recurrent pancreatitis begins with bed rest and fasting. Diet is an important component of the treatment complex. Hunger prescribed for no more than one day is subsequently replaced by the gradual introduction of foods from the 5p diet, characterized by mechanical, chemical and thermal sparing of the gastrointestinal tract and the exclusion of pancreatic secretion stimulants.

Therapy is aimed at eliminating microcirculation disorders in the pancreas, ensuring its functional rest, replacing impaired functions and reducing the aggressiveness of damaging factors.

In connection with these tasks, patients are prescribed infusion therapy aimed at eliminating microcirculatory disorders and detoxification. This therapy also includes drugs that have anti-enzyme activity, such as Aprotinin, as well as drugs that affect microcirculation - Trental, Curantil, Dalargin.

Functional rest of the pancreas is ensured by:

- a diet that reduces nutritional stimulation of the organ;

- antisecretory drugs: M-anticholinergics (selective - pirenzepine), H2-blockers (famotidine) or proton pump inhibitors, which reduce gastric secretion and, accordingly, stimulation of the pancreas with acid;

- preparations of pancreatic enzymes that inhibit gastric secretion according to the principle of negative feedback, destroying releasing peptides produced in the mucous membrane of the duodenum.

Somatostatin analogue drugs (octreotide) are highly effective, and have now become key in the treatment of acute pancreatitis and exacerbation of chronic pancreatitis. Somatostatin, produced mainly in the digestive organs and the central nervous system, is one of the most important neurotransmitters in the human and animal body, regulates (suppresses) secretory processes, including in the pancreas, proliferation, contractility of smooth muscles, motility of the digestive organs , intestinal absorption and many other processes.

Complex therapy at the first stage of intensive care may also include glucocorticoid hormones and antibiotics.

An important task for normalizing the condition of the pancreas is to ensure the outflow of pancreatic secretions, the main solution to which is the prescription of antispasmodics and prokinetics. Among antispasmodics, mebeverine (Duspatalin) occupies a special place due to its dual effect: pronounced antispasmodic, on the one hand, and prevention of sphincter hypotension, on the other. Among prokinetics, trimebutine (Trimedat) is preferred, as it has a modulating effect on the motility of the digestive organs.

The optimal way to correct exocrine pancreatic insufficiency in children with chronic recurrent pancreatitis is the administration of microspheres (Creon 10,000) in a dose of 3–6 capsules per day, which quickly eliminates steatorrhea. Moreover, after long-term (1–2 months) therapy, it is possible to discontinue the drug, which indicates the high compensatory ability of the child’s pancreas. As for the treatment of a patient with exacerbation of chronic recurrent pancreatitis, our experience shows the advisability of short-term (in the absence of signs of pancreatic insufficiency) administration of pancreatic enzymes against the background of expanding the diet after a period of intensive therapy in a dose adequate to the volume and nature of nutrition, usually up to 4 capsules of Creon 10,000 per day.

Of course, an integral task in the treatment of pancreatitis is to eliminate the causes that caused its development. This task becomes especially important in reactive states of the pancreas due to their potential reversibility. Additionally, medications that improve microcirculation (Curantil, Trental, etc.) may be prescribed.

Surgical treatment is required in case of progression of destruction, development of pancreatic necrosis and ineffectiveness of conservative therapy.

Despite the certain success of the treatment, much more effort is required to increase its effectiveness. An important promising task is to reduce the activity and stimulate the reverse development of sclerotic changes in the pancreatic parenchyma, which today is practically impossible to solve.

In general, the problem of pancreatitis in children requires further study at the current level of knowledge and technical capabilities, including aspects of terminology and associated epidemiology, etiology and pathogenesis, as well as diagnosis and treatment. The achievements available in this direction only highlight the variety of still unresolved problems.

S. V. Belmer , Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor T. V. Gasilina , Candidate of Medical Sciences, Russian State Medical University , Moscow

Diagnosis of pancreatitis

Gastroenterologists and pediatricians at SM-Doctor are specialists with experience of 10 years or more. Thanks to the extensive experience and modern equipment that our clinic is equipped with, doctors can quickly identify pancreatitis even in the early stages of development. All this creates optimal conditions for prescribing adequate treatment and, consequently, restoring the child’s condition in the shortest possible time. The doctor makes a preliminary diagnosis of pancreatitis at the first consultation. Anamnesis of the disease and features of the clinical picture help him with this. To verify the diagnosis, the following additional studies are prescribed:

- general clinical analysis of blood and urine;

- biochemical blood test - special attention is paid to the level of alpha-amylase;

- ultrasound scanning (ultrasound) of the abdominal organs;

- stool test for elastase-1;

- CT, MRI of the abdominal cavity (if necessary in complex clinical cases).

If there is a suspicion of concomitant dysfunction of other internal organs and systems, the gastrologist refers the child for consultation to related specialists (infectious disease specialist, neurologist, nephrologist).

Treatment of pancreatitis

The key aspect of the treatment of pancreatitis is to ensure the maximum possible functional rest of the gland in the acute phase of inflammation.

A significant decrease in the secretory function of the organ, created artificially, contributes to the natural attenuation of the activity of the pathological process. For this purpose, doctors prescribe bed rest and fractional consumption of still water (in the first days) with a gradual expansion of the diet through the use of pureed foods. To relieve the clinical picture with the help of medications, the following groups of drugs are used:

- analgesics and antispasmodics - to eliminate pain;

- antisecretory drugs;

- enzymes - to stabilize digestive function;

- protease inhibitors.

Anomalies of pancreas development may sometimes require surgical treatment.

When a bacterial cause of the disease is identified, the doctor additionally uses antibiotics to destroy the pathogen. Prevention of the disease involves following a rational diet that is appropriate for the baby’s age, and timely treatment of other gastrointestinal diseases.

“SM-Doctor” is a modern clinic specializing in providing a full package of services for the diagnosis and treatment of all kinds of gastrointestinal diseases of children from 0 to 18 years old. Thanks to high-tech equipment and the extensive experience of our doctors, we guarantee a rapid improvement in the well-being of each patient. Contact qualified specialists at a convenient time!

Pancreatitis in early childhood

Diagnosis and treatment of pancreatitis in children

Pancreatitis can be diagnosed even in infants. As a rule, the cause of the disease at this age is congenital enzyme deficiency or malformations of the digestive system. Pancreatitis can also be a manifestation of mumps (“mumps”). In some cases, the cause of pancreatitis in young children is nutritional imbalances, injuries, or medications.

A small child is not able to complain where it hurts. With pancreatitis, the baby cries hysterically and quickly loses weight. His tummy is swollen. With such symptoms, the child should be shown to a doctor as soon as possible in order to establish a diagnosis and begin treatment.