Pharmacological properties of the drug Felodip

Pharmacodynamics. Felodip is a dihydropyridine derivative, a selective blocker of L-type calcium channels. It has a high affinity for smooth muscle cells of peripheral arterioles and coronary arteries. Felodip dilates arterioles, reduces peripheral vascular resistance and blood pressure. In therapeutic doses it has virtually no effect on myocardial contractility. Felodip has an antianginal effect by reducing vascular resistance of the coronary vessels, improving coronary circulation and oxygen supply to the myocardium, and also reduces afterload on the heart, which leads to a decrease in myocardial oxygen demand. Felodip improves exercise tolerance and reduces the frequency of attacks in patients with stable angina, and has an anti-ischemic effect in vasospastic angina. The primary hemodynamic effect of Felodip is a decrease in general peripheral vascular resistance, thereby reducing blood pressure. This effect is dose dependent. As a rule, a decrease in blood pressure is observed 2 hours after a single dose and lasts for at least 24 hours, the T/P ratio (plateau/peak) reaches a value well above 50%. There is a positive relationship between the concentration of the drug in the blood plasma, the level of decrease in OPSS and the decrease in blood pressure. Felodip has a slight natriuretic and diuretic effect, since it reduces tubular reabsorption of sodium. Felodip does not affect the daily excretion of potassium. In patients with reduced renal function, glomerular filtration rate may increase during treatment with Felodip. Felodip is well tolerated by patients after kidney transplantation. The drug does not affect the concentration of glucose in the blood and the lipid profile. Pharmacokinetics. Felodip is completely absorbed into the gastrointestinal tract. Bioavailability is about 15% and does not depend on the dose taken (first pass effect through the liver). 99% of Felodipa binds to blood plasma proteins, mainly albumin. Due to the peculiarities of the dosage form, the prolonged release of felodipine extends the absorption phase and ensures its uniform concentration in the blood plasma over 24 hours. The drug penetrates the BBB and the placental barrier, and into breast milk. Felodipine is completely metabolized in the liver, all of its metabolites are inactive. The half-life of felodipine is 25 hours. With prolonged use, accumulation of the active substance does not occur. In elderly patients and with impaired liver function, plasma concentrations of felodipine are higher than in young patients. The pharmacokinetics of Felodip does not change in patients with impaired renal function, including those undergoing hemodialysis. About 70% of the dose taken is excreted in the urine, and 30% is excreted in the feces in the form of metabolites. 0.5% of the dose taken is excreted unchanged in the urine.

Felodipine Canon (2.5 mg, 5 mg, 10 mg)

Pharmacodynamics

Felodipine is a slow calcium channel blocker (SCBC) used to treat hypertension and stable angina. Felodipine is a dihydropyridine derivative and is a racemic mixture. Felodipine reduces blood pressure (BP) by reducing total peripheral vascular resistance, especially in arterioles. The conductivity and contractility of vascular smooth muscle is inhibited by affecting the calcium channels of cell membranes. Due to its high selectivity for arteriole smooth muscle, felodipine in therapeutic doses does not have a negative inotropic effect on cardiac contractility or conduction. Felodipine relaxes the smooth muscles of the respiratory tract. Felodipine has been shown to have little effect on gastrointestinal motility. With long-term use, felodipine does not have a clinically significant effect on blood lipid concentrations. In patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, no clinically significant effect on metabolic processes was observed when using felodipine for 6 months. Felodipine may also be prescribed to patients with reduced left ventricular function receiving standard therapy and to patients with asthma, diabetes mellitus, gout or hyperlipidemia.

Antihypertensive effect: a decrease in blood pressure when taking felodipine is due to a decrease in peripheral vascular resistance. Felodipine effectively reduces blood pressure in patients with arterial hypertension both in the supine, sitting and standing positions, at rest and during physical activity. Since felodipine has no effect on venous smooth muscle or adrenergic vasomotor control, orthostatic hypotension does not occur. At the beginning of treatment, as a result of a decrease in blood pressure while taking felodipine, a temporary reflex increase in heart rate (HR) and cardiac output may be observed. An increase in heart rate is prevented by the simultaneous use of beta-blockers with felodipine. The effect of felodipine on blood pressure and peripheral vascular resistance correlates with the plasma concentration of felodipine. At steady state, the clinical effect persists between doses and the reduction in blood pressure persists for 24 hours. Treatment with felodipine leads to regression of left ventricular hypertrophy. Felodipine has natriuretic and diuretic effects and does not have a kaliuretic effect. When taking felodipine, tubular reabsorption of sodium and water decreases, which explains the absence of salt and fluid retention in the body. Felodipine reduces vascular resistance in the kidneys and increases renal perfusion. Felodipine has no effect on glomerular filtration rate and albumin excretion. The use of felodipine in combination with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and beta-blockers. If necessary, use diuretics to reduce diastolic blood pressure to less than 90 mmHg. in 93% of patients.

The use of BMCC, dihydropyridine derivatives as an initial course of therapy followed by the addition of beta-blockers, if necessary, does not affect the mortality rate from cardiovascular diseases compared with standard therapy with beta-blockers and/or diuretics. For the treatment of arterial hypertension, felodipine can be used alone or in combination with other antihypertensive drugs such as beta-blockers, diuretics or ACE inhibitors. Anti-ischemic effect: the use of felodipine leads to an improvement in blood supply to the myocardium due to dilation of the coronary vessels. Reducing the load on the heart is achieved by reducing peripheral vascular resistance (reducing the load overcome by the heart muscle), which leads to a decrease in myocardial oxygen demand. Felodipine relieves spasm of coronary vessels, improves myocardial contractility and reduces the frequency of angina attacks in patients with stable angina pectoris. At the beginning of therapy, a temporary increase in heart rate may be observed, which can be controlled by the administration of beta-blockers. The effect occurs after 2 hours and lasts for 24 hours.

For the treatment of stable angina, felodipine can be used in combination with beta-blockers or as monotherapy.

Pharmacokinetics

The systemic bioavailability of felodipine is approximately 15% and does not depend on the timing of meals. However, the rate of absorption, but not its extent, may vary depending on the timing of meals, and the maximum plasma concentration is thus increased by approximately 65%. The maximum concentration in the blood plasma is achieved after 3-5 hours. The drug binds to blood plasma proteins by 99%. The volume of distribution at steady state is 10 l/kg. The half-life is approximately 25 hours, the plateau phase is reached within approximately 5 days. Does not accumulate even with long-term use. The total plasma clearance averages 1200 ml/min. Reduced clearance in elderly patients and in patients with reduced liver function leads to increased plasma concentrations of felodipine. However, age only partially explains individual changes in plasma concentrations of felodipine. Felodipine is metabolized in the liver under the action of the CYP3A4 isoenzyme; all identified metabolites do not have a vasodilating effect (hemodynamic activity). About 70% of the dose taken is excreted in the form of metabolites through the kidneys, the rest through the intestines. Less than 0.5% is excreted unchanged by the kidneys. If renal function is impaired, the plasma concentration of felodipine does not change, but accumulation of inactive metabolites is observed. Felodipine is not eliminated by hemodialysis.

Use of the drug Felodip

AH (arterial hypertension) The dose is determined individually (including in elderly people). The initial dose is usually 5 mg 1 time per day. If necessary, the dose can be increased or another antihypertensive drug added. The maintenance dose is usually 5–10 mg once a day. To determine your individual dose, it is best to use 2.5 mg tablets. For use in the elderly, the initial dose is 2.5 mg/day. Stable angina. Treatment begins with a dose of 5 mg 1 time per day; if necessary, the dose can be increased to 10 mg 1 time per day. The maximum daily dose is 20 mg in 1 dose. In patients with severe liver dysfunction, the therapeutic dose should be reduced (the recommended initial dose is 2.5 mg/day). In patients with impaired renal function, changes in pharmacokinetics are insignificant, so dose adjustment of the drug is not required. It is better to take the drug in the morning before meals or after a light breakfast. Felodip tablets should not be chewed, divided or crushed. There is no experience with the use of Felodip in pediatrics.

Possibilities of felodipine in the treatment of arterial hypertension

About the article

9969

0

Regular issues of "RMZh" No. 21 dated September 25, 2008 p. 1416

Category: Cardiology

Author: Nedogoda S.V. 1 1 FSBEI HE Volgograd State Medical University of the Ministry of Health of Russia, Volgograd, Russia

For quotation:

Nedogoda S.V. Possibilities of felodipine in the treatment of arterial hypertension. RMJ. 2008;21:1416.

In Russia, felodipine, a representative of calcium antagonists (CA) from the subgroup of dihydropyridines, has not quite justifiably taken a backseat in the treatment of arterial hypertension (AH) compared to amlodipine, although throughout the world it continues to firmly occupy a leading position among a large number of antihypertensive drugs . This is due not only to the clinical and pharmacological characteristics of the drug [9,21,26], but also to the currently available large evidence base for its use in hypertension.

It seems that felodipine is going into the shadows in our country due to two most important reasons. Firstly, in Russia for a long time there were no high-quality generics of felodipine on the pharmaceutical market. And, secondly, in recent years, a number of large studies have been completed on another representative of this group of calcium antagonists - amlodipine, which, naturally, allowed it to come into the spotlight.

In contrast to non-dihydropyridine AKs - verapamil and diltiazem - dihydropyridine antagonists, including felodipine, have a slight effect on myocardial contractility and do not affect the function of the sinus node and atrioventricular conduction at all. These properties largely determine the features of clinical use [26]. Felodipine is a modern second-generation AK from the group of dihydropyridine derivatives. Moreover, felodipine has vascular selectivity 7–10 times greater than nifedipine [26].

When taken orally, felodipine is rapidly absorbed and its maximum concentration is observed after 1 hour. The relatively low bioavailability (about 15%) is due to the high rate of metabolism of the drug in the liver. In patients with liver cirrhosis, due to the high rate of presystemic elimination, it is necessary to reduce the daily dose of the drug. But for the same reason, in chronic renal failure there is no need to adjust the dose of felodipine. Up to 99% of felodipine is bound to protein. The half-life (T1/2) of felodipine averages about 14 hours, which ensures that its concentration in the blood remains constant. For the same reason, its use is much less likely to cause side effects typical of short-acting AKs. In terms of its pharmacokinetic parameters (Table 1), felodipine “loses” only to amlodipine [2], and clinical studies have not identified a “winner” [4,7,16,20,22–25,28].

The hypotensive effect develops within 15–45 minutes. after oral administration and has a dose-dependent nature, and its concentration in the blood plasma positively correlates with a decrease in vascular peripheral resistance and blood pressure (BP). At the beginning of treatment, a decrease in blood pressure may be accompanied by a transient increase in heart rate, but with long-term use, activation of the sympathetic-adrenal system is not observed [10,12,27]. Felodipine also has a mild diuretic effect (26). The optimal dosage regimen for felodipine for hypertension is considered to be 5–10 mg 1–2 times a day. It is important that during therapy with felodipine there is a significant regression of hypertrophied left ventricular myocardium (LVH). After several months of therapy, the mass of the myocardium, the thickness of the interventricular septum and the posterior wall of this ventricle decrease (according to echocardiography). Felodipine is a metabolically neutral drug, including in problematic patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) [5,13]. After stopping treatment with felodipine, no withdrawal syndrome is observed [3].

The undoubted advantages of felodipine include its antianginal effect [26].

The evidence base for the use of felodipine in hypertension is currently, of course, one of the most powerful.

First of all, it is necessary to remember that one of the fundamental studies in modern cardiology, HOT (Hypertension Optimal Treatment study), in which 18,790 patients took part, felodipine was used as the main drug. This study examined the effect of the degree of blood pressure reduction on the risk of developing cardiovascular diseases, as well as on mortality in patients with hypertension. The results of the HOT study [14] convincingly demonstrated that effective treatment of hypertension can be achieved using felodipine as the main antihypertensive drug. Thus, at the end of the study, 78% of patients continued to take felodipine as primary therapy, with only 41% of patients using it in combination with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACE inhibitor) and 28% with the beta-blocker metoprolol. Consequently, for about four years, antihypertensive monotherapy was effective in almost half of the patients, which is undoubtedly a very good indicator. It was shown that the good antihypertensive efficacy and tolerability of felodipine were independent of age and concomitant pathology, and the incidence of cardiovascular diseases and complications during treatment including felodipine was significantly lower than in earlier studies using a diuretic or beta-blocker. , due to effective BP control in the HOT study.

The HOT study demonstrated the high effectiveness of the combination of felodipine with metoprolol, an ACE inhibitor and acetylsalicylic acid. The advisability of using felodipine for hypertension in the elderly was also once again confirmed [8], which was previously shown in the STOP–Hypertension 2 study (Swedish Trial in Old Patients with Hypertension 2).

Unfortunately, in Russia, practicing doctors are poorly informed about the results of the relatively recently completed large study FEVER (Felodipine EVEnt Reduction), although the most famous specialist in the field of hypertension Prof. Alberto Zanchetti put it in line with studies such as PROGRESS, ALLHAT and others [17,18]. This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study assessed whether felodipine or placebo could reduce the risk of cardiovascular events in nearly 10,000 hypertensive patients with a baseline high risk of these events after their blood pressure had been significantly reduced by hydrochlorothiazide therapy. at a low dose, and felodipine was used to achieve its target level.

This study included hypertensive patients aged 50–79 years, of both sexes, with SBP/DBP <210/115 mmHg, on antihypertensive medication or with SBP 160–210 mmHg. or DBP 95–115 mm Hg. without antihypertensive therapy. Patients 50–60 years old had to have ≥2 risk factors or clinical manifestations of diseases, and patients 61–79 years old had to have ≥1 risk factor or clinical manifestations of diseases.

The main cardiovascular risk factors were male gender, smoking, total cholesterol ≥240 mg/dL during the last year or lipid-lowering therapy, compensated diabetes, LVH, proteinuria and excess body weight (BMI >27 kg/m2). Major cardiovascular events included myocardial infarction, stroke, stable angina or clinical manifestations of coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, peripheral circulatory disorders and transient ischemic attacks.

Patients were initially treated with hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) 12.5 mg/day monotherapy for 6 weeks (other antihypertensives were excluded in 89% of previously treated patients), followed by 9800 patients with DBP 90–100 mmHg. and/or SBP 140–160 mmHg. were randomized into 2 groups: some received HCTZ plus felodipine 5 mg/day, others HCTZ plus placebo.

The addition of a diuretic or other antihypertensive drugs was allowed at the discretion of the study physician. The most commonly prescribed medications were diuretics, ACE inhibitors, and ACE inhibitors, but 66.1% of patients in the felodipine group and 57.7% in the placebo group remained on these medications throughout the study period. The study ended when the required number of primary endpoints (400) were recorded.

The mean SBP/DBP at screening was 159/93 mmHg. After 6 months of follow-up, the mean SBP/DBP was 142.5/85 mmHg. in the placebo group versus 137.3/82 mm Hg. in the felodipine group. These group differences remained constant throughout the study period for a mean reduction in SBP/DBP of 4/2 mmHg. By the end of follow-up (60 months), more patients in the felodipine + HCTZ group achieved SBP <140 mmHg. and DBP <90 mm Hg. compared with the placebo + HCTZ group (Table 2).

The FEVER study showed that the number of strokes (fatal and non-fatal) was significantly lower (–28%) in the felodipine group (Table 3). It should be noted that this reduction in the risk of stroke was detected while taking diuretics, which are considered one of the most effective means in reducing the risk of stroke.

Significant reductions in the felodipine + HCTZ group versus placebo were also found in the secondary outcomes of cardiovascular events (-28%), all cardiovascular events (-28%), all cardiac events (-34%), all-cause mortality (-30%), cardiac –vascular mortality (–32%), coronary events (–32%), HF (–24%) and cancer (–40%).

All treatment regimens in the study were well tolerated, although the felodipine group experienced more frequent hot flashes (1.4% vs. 0.2%, p<0.001) and leg swelling (1.0% vs. 0.37%, p< 0.001), but symptoms of fatigue were significantly less common (0.64% vs. 1.05%, p=0.037) compared to the placebo group. There were no differences in the incidence of dizziness, headache or palpitations between the two groups.

Commenting on the results of the FEVER study, prof. Alberto Zanchetti noted that even differences in SBP/DBP ratios of 4/2 mmHg. when comparing calcium antagonists versus placebo, may be accompanied by a further reduction in cardiovascular events, even in patients at low cardiovascular risk compared with patients in most recent studies (Syst-Eur, Syst-China, HOPE, PATS, PROGRESS, ALLHAT, SCOPE, LIFE , VALUE, INVEST, EUROPA, ACTION), in which patients with hypertension initially had a high risk of developing cardiovascular complications. Also noteworthy was a significant reduction in the incidence of cancer in patients in the felodipine group.

It seems important that felodipine demonstrated an increase in the hypotensive effect and a decrease in the incidence of side effects when combined with enalapril (Enalapril Felodipine ER Factorial Study), a slowdown in chronic kidney disease in patients with hypertension and non-diabetic nephropathy when combined with ramipril (The Nephros Study), a marked decrease LVH in combination with irbesartan (SILVER) and a decrease in blood pressure in people with refractory hypertension in whom therapy with two antihypertensive drugs was ineffective (Cooperative Study Group) [6].

Today, claims that therapy with amlodipine and other calcium antagonists are pharmacoeconomically preferable to treatment with felodipine seem unfounded [4,7,16,19, 22–25,28]. Thus, after transferring 238 patients from 10 mg of amlodipine to 10 mg of felodipine [20], a tendency to a further decrease in blood pressure and a significant decrease in the number of heartbeats was observed (Table 4). However, concomitant antihypertensive therapy did not change (Table 5).

After the appearance in Russia of a high-quality generic felodipine - FELODIP (Teva company), the possibilities of reducing treatment costs are significantly reduced, despite the fact that one of the most modern AKs with a large evidence base and experience in clinical use is used. It should be noted that in terms of its pharmacokinetic parameters, generic FELODIP is practically no different from the original drug, which is confirmed by the results of a randomized crossover study of 48 healthy individuals. At the same time, the difference from the original in most pharmacokinetic parameters did not exceed 2%, with an acceptable level of 10%.

Thus, felodipine significantly expands the possibilities of mono- and combination therapy with other drugs, primarily ACE inhibitors [1,11] not only in patients with only hypertension, but also such concomitant diseases as diabetes, coronary artery disease, gout, broncho-obstructive syndrome, COPD . In addition, there is evidence of the high effectiveness of the drug for the treatment of hypertension in pediatric practice [15] and in the prevention of nephropathy during contrast studies [29].

References 1. Bainbridge AD, Macfadyen RJ, Stark S. et al. The antihypertensive efficacy and tolerability of a low dose combination of ramipril and felodipine ER in mild to moderate essential hypertension // Brit. J. Clin. Pharmacology. – 1993. – Vol. 36. – P. 323–330. 2. Baranda AB, Mueller CA, Alonso RM et al. Quantitative determination of the calcium channel antagonists amlodipine, lercanidipine, nitrendipine, felodipine, and lacidipine in human plasma using liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry // Ther. Drug Monit. – 2005. – Vol. 27. – P. 44–52. 3. Black HR, Elliott WJ, Weber MA et al. One–year study of felodipine or placebo for stage 1 isolated systolic hypertension // Hypertension. – 2001. – Vol. 38. – P. 1118–1123. 4. Blivin SJ, Pippins J., Annis LG, Lyons F. A comparative analysis of amlodipine and felodipine in a military outpatient population: efficacy, outcomes, and cost considerations // Mil. Med. – 2003. – Vol. 168. – P. 530–535. 5. Capewell S., Collier A., Matthews D. et al A trial of the calcium antagonist felodipine in hypertensive type 2 diabetic patients// Diabet–Med.– 1989. Vol. 6.– P. 809–12. 6. Cooperative Study Group. Felodipine vs hydralazine: a controlled trial as third line therapy in hypertension // Br J Clin Pharmacol. – 1986.– Vol. 21. P. 621–626. 7. Dimenas E, Dahlof C, Olofosson B, Wiklund I. An instrument for quantifying subjective symptoms among untreated and treated hypertensives: development and documentation // J Clin Res Pharmacoepidemiol. – 1990. –Vol. 4. P:205–17. 8. Ekbom T., Linjer E., Hedner T. et al. Cardiovascular events in elderly patients with isolated systolic hypertension. A subgroup analysis of treatment strategies in STOP–Hypertension–2 // Blood Press. – 2004. – Vol. 13. – P. 137–141. 9. Ernst ME, Dellsperger KC, Phillips BG. Comparison of amlodipine and felodipine on 24–hour ambulatory blood pressure in hypertensive patients [abstr] //Am J Hypertens. – 2001. – P.118A. 10. Ficek J., Kokot F., Chudek J. et al. Influence of antihypertensive treatment with perindopril, pindolol or felodipinon plasma leptin concentration in patients with essential hypertension // Horm. Metab. Res. – 2002. – Vol. 34. – P. 703–708. 11. Francischetti A., Ono H., Frohlich ED Renoprotective effects of felodipine and/or enalapril in spontaneously hypertensive rats with and without L–NAME // Hypertension. – 1998. – Vol. 31. – P. 795–801. 12. Grassi G., Seravalle G., Turri C. Short-versus long-term effects of different dihydropyridines on sympathetic and baroreflex function in hypertension // Hypertension. – 2003. – Vol. 41. – P. 558–562. 13. Hishikawa K., Luscher T. Felodipine inhibits free–radical production by cytokines and glucose in human smooth muscle cells // Hypertension. – 1998. – Vol. 32. – P. 1011–1015. 14. Jonsson B., Hansson L., Stalhammar NO Health economics in the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) study: costs and cost-effectiveness of intensive blood pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension // J. Intern. Med. – 2003. – Vol. 253. – P. 472–480. 15. Kotchen TA, Mansour G., Mansour AJ Calcium channel blockers (felodipine) and pediatric essential hypertension // Curr. Hypertens. Rep. – 2003. – Vol. 5. – P. 484–485. 16. Krantz SR, Rase RS, Peipho RW. Retrospective analysis of formulary transition at large metropolitan HMO: nifedipine GITS to felodipine ER // J Managed Care Pharm. – 1996.–Vol.2.– P.642–6. 17. Lisheng L, Yuqing Z, Guozhang L et al. FEVER study: a trial further supporting the concept of a blood pressure–independent stroke protective effect by dihydropyridines // Journal of Hypertension. – 2006. – Vol. 24. P.1215–1216. 18. Liu L, Zhang Y, Liu G, Li W, Zhang X, Zanchetti A. The Felodipine EVEnt Reduction (FEVER) study: A randomized long–term placebo controlled trial in Chinese hypertensive patients – design and principal results // J Hypertens . – 2005. Vol. 23(suppl 2).– S118: Abstract P1.347. 19. Mamdani MM, Reisig CJ, Stevenson JG. Cost analysis of therapeutic interchange of calcium channel blockers for the treatment of hypertension: unexpected results from a conversion program // J Managed Care Pharm. – 2000. – Vol.6.–P.390–4. 20. Manzo BA, Matalka MS, Ravnan SL Evaluation of a therapeutic conversion from amlodipine to felodipine // Pharmacotherapy. – 2003. – Vol. 23. – P. 1508–1512. 21. Mayer O. Calcium channel blockers in the treatment of hypertension and ischemic coronary disease. Conflicts in their evaluation // Cas. Lek. Cesk. – 1998. – Vol. 6. – P. 216–219. 22. Menzin J, Lang K, Elliott WJ et al. Adherence to calcium channel blocker therapy in older adults: a comparison of amlodipine and felodipine // J. Int. Med. Res. – 2004. – Vol. 32. – P. 233–239. 23. Oatis G, Stowers AD. Conversion from amlodipine to felodipine ER: did the change fulfill expectations? //Formulary.– 2000.Vol. 35.– P.435–42. 24. Ostergren J, Isaksson H, Brodin U, Schwan A, Ohman P. Effect of amlodipine versus felodipine extended release on 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure in hypertension // Am J Hypertens. – 1998. – Vol.11. – P.690–6. 25. Romito R., Pansini MI, Perticone F. et al. Comparative effect of lercanidipine, felodipine, and nifedipine GITS on blood pressure and heart rate in patients with mild to moderate arterial hypertension: the lercanidipine in adults (LEAD) study // J. Clin. Hypertension (Greenwich). – 2003. – Vol. 5. – P. 249–253. 26. Scholze JE Differential therapy with calcium antagonists // Herz. – 2003. – Vol. 28. – P. 754–763. 27. Smith SA, Mace PJ, Littler WA Felodipine, blood pressure, and cardiovascular reflexes in hypertensive humans // Hypertension. – 1986. – Vol. 8. – P. 1172–1178. 28. Walters J, Noel H, Folstad J, Kapadia V, White CM. Prospective evaluation of the therapeutic interchange of felodipine ER for amlodipine in patients with hypertension// Hosp Pharm.– 2000.– Vol. 35. – P.48–51. 29. Wongand GTC, Irwin MG Contrast-induced Nephropathy // Br J Anaesth. – 2007. – Vol.99. P474–483.

Side effects of the drug Felodip

Like other calcium antagonists, felodipine can cause facial flushing, headache, palpitations, dizziness, and fatigue. These reactions are temporary and occur more often at the beginning of treatment or when the dose is increased. Depending on the dose, edema in the ankle area may occur as a result of precapillary vasodilation. Patients with gum disease or periodontitis may experience mild swelling of the gums; this can be prevented by maintaining good oral hygiene. As with the use of other dihydropyridines, in some cases an increase in the manifestations of angina was noted, mainly at the beginning of treatment. Cardiovascular system: tachycardia, palpitations, rarely - syncope, peripheral edema, facial flushing. Central and peripheral nervous system: headache, dizziness, rarely - paresthesia. Gastrointestinal tract: nausea, abdominal pain, in isolated cases - hyperplasia, inflammation of the gums. Liver: in isolated cases, an increase in the level of liver transaminases is noted. Musculoskeletal system: rarely - pain in joints and muscles. Allergic reactions: facial flushing, skin rash, itching; rarely - urticaria; in isolated cases - photosensitivity, vasculitis. Urinary system: in isolated cases - pollakiuria. Other: rarely - fatigue, sexual dysfunction, impotence; in isolated cases - hypersensitivity reactions, for example angioedema, increased body temperature.

Special instructions for the use of the drug Felodip

During treatment with Felodip, you should refrain from engaging in potentially dangerous activities that require concentration and speed of psychomotor reactions. Patients with angina pectoris should take into account that the drug can cause arterial hypotension, which can cause the appearance or intensification of myocardial ischemia. If liver function is impaired, it is necessary to adjust the dose of the drug. Felodip does not affect the concentration of glucose in the blood plasma and the lipid profile. Felodipine should not be taken in combination with grapefruit juice due to the fact that the latter contains a flavonoid that increases the concentration of felodipine in the blood serum. Felodip is effective and well tolerated by patients regardless of gender and age, persons with asthma, other obstructive pulmonary diseases, impaired renal function, patients with diabetes mellitus, gout, hyperlipidemia, Raynaud's syndrome, and after lung transplantation. Felodip is prescribed with caution, especially in combination with β-adrenergic receptor blockers, to patients with severe heart failure.

Arterial hypertension (AH) has long gone beyond the scope of a purely medical problem. The widespread prevalence and severe consequences of this disease have made it a social problem. In Russia, as in most economically developed countries, hypertension is one of the most common cardiovascular diseases (CVD). According to a study conducted in 2008 [1], the prevalence of hypertension among the population of the Russian Federation was 40.8%. The arsenal of modern medicine contains a lot of powerful antihypertensive drugs that can significantly increase the life expectancy of patients and improve its quality. But, despite this, as international epidemiological studies have shown[2], the target level of blood pressure (BP) in real practice is achieved in no more than 40–60% of cases. The reason for inadequate blood pressure control is not so much the lack of effectiveness of the drugs as the low adherence of patients to treatment. In Russia, slightly more than two-thirds of patients with hypertension take antihypertensive drugs – 69.5%[1]. Of these, only 27.3% are effectively treated [1]. The peculiarities inherent in hypertension itself are partly to blame for low adherence. Most patients with hypertension do not have clinical symptoms, so only 40–50% of them actually begin to feel better during treatment [3]. In many patients, their health even worsens due to too rapid reduction in blood pressure or side effects of medications. Therefore, the drugs taken must, in addition to high antihypertensive effectiveness, be well tolerated and have a convenient dosage regimen. On the other hand, in our country, the first place among the factors influencing compliance with doctor’s recommendations is often “lack of funds,” and among those influencing the choice of a particular drug is its cost and presence in the list of DLO (additional drug provision) [4]. Therefore, when conducting pharmacotherapy, the doctor has to solve the problem of choosing a drug, based on data not only on its clinical effectiveness, but also on its real cost. Many generic drugs have therapeutic activity and a spectrum of side effects comparable to the original, but are significantly cheaper, since their creation involves significantly lower costs.

One of the successful generic drugs is the generic felodipine Felodip (TEVA), which is on the DLO list and is widely used by primary care physicians in outpatient practice. We carried out a study, the purpose of which was not only to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of the drug in patients with hypertension, but also to analyze the factors influencing adherence to therapy in real outpatient practice.

Material and methods

Open observation was carried out in 84 district clinics in Moscow. 185 cardiologists participated in the study. The study included 5474 patients with hypertension, men and women over 18 years of age, with a baseline office systolic blood pressure (SBP) of 140–179 mmHg. Art. and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) 99–100 mm Hg. Art., with or without antihypertensive therapy. A prerequisite was the absence of regular therapy with calcium antagonists (CA) for at least two weeks before inclusion in the study. In accordance with the ESH/ESC criteria [5], all patients had a high or very high risk of cardiovascular complications. Exclusion criteria were symptomatic hypertension, myocardial infarction or stroke suffered less than 3 months ago, decompensated heart failure, decompensated diabetes mellitus (DM) or requiring insulin, severe liver and kidney dysfunction, a history of intolerance to AA, aortic stenosis, for women - pregnancy and lactation.

In addition to a general clinical examination, all patients included in the study had their blood pressure measured in the doctor’s office (office blood pressure) and their body mass index (BMI) was calculated. An assessment of medical history, risk factors, and concomitant therapy was carried out. Quality of life was determined using a visual analogue scale (VAS). The patient's adherence to drug therapy was assessed using the Morisky–Green test [6].

Patients who answered “no” to these questions more than 3 times (scoring more than 3 points) were considered compliant:

- Have you ever forgotten to take your medications? (no Yes).

- Are you sometimes careless about the hours you take your medications? (no Yes).

- Do you skip taking medications if you feel well? (no Yes).

- If you feel unwell after taking medication, do you skip the next dose? (no Yes).

Study design

According to the results of the Morisky-Green test at the first visit, patients were divided into two groups: the first - with low adherence to treatment (LAT), the second - with high adherence to treatment (HPT).

Felodipine was prescribed at a dose of 5–10 mg once daily. Dose adjustments in both groups, if necessary, were made at week 4 of the study. Basic therapy remained unchanged. For the final visit (after 8 weeks), the patient was again invited to the clinic. The percentage of patients who achieved the target blood pressure level (office blood pressure - less than 140/90 mm Hg), the percentage of patients who had a decrease in DBP by more than 10 mm Hg were determined. Art. and SBP more than 20 mm Hg. Art. from the initial level. Tolerability of the drug (good/bad), quality of life was assessed according to the results of the visual analogue scale (starting and end points). The percentage of patients who noted various side effects was determined.

Statistical analysis was carried out using the SAS software package (version 6.12). During the analysis, average values (M) and their standard errors (m) were calculated. The significance of differences in mean values was assessed using the Student's t test (t). Parametric and nonparametric analysis programs were used. The results were considered significant at p < 0.05. Data are presented as M ± m. A logistic regression model was used to study adherence, and odds with 95% confidence intervals (CI) are given for a number of adherence-informative variables.

Results and discussion

Characteristics of groups

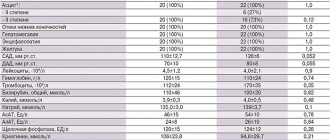

4816 charts of patients who completely completed the study were analyzed (Table 1).

. Characteristics of patient groups.

The groups did not differ in age, duration of hypertension, family history, BMI, and degree of physical activity. In the NPL group, the levels of SBP and DBP were initially significantly higher than in the HPL group. It was noted that associated diseases were less common in the NPL group. Patients in this group more often received drugs according to the DLO system (p = 0.001). At the same time, they were less likely to take drugs such as AA, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), aspirin, nitrates, and antiarrhythmic drugs. The average duration of hypertension did not differ between groups, but the proportion of patients with newly diagnosed hypertension was higher in the NLP group. The average daily dose of felodipine in the groups in the 4th week of taking it was 6.9 mg/day in the first group, 6.7 mg/day in the second. At the 8th week of dosing, the doses did not differ significantly.

Blood pressure dynamics

During treatment, after 4 and 8 weeks, a significant decrease in both SBP and DBP levels was observed in both groups. SBP levels decreased by an average of 31 mmHg. Art., DBP – by 15 mm Hg. Art. (p < 0.0001). The dynamics of average office blood pressure are shown in Fig. 1 and 2.

By the end of the study, 50.6% of patients in the NPL group and 47.7% of patients in the IDP group reached the target blood pressure level. SBP < 140 mm Hg. Art. or a decrease of 20 mm Hg. Art. or more, as well as DBP < 90 mm Hg. Art. or a decrease of 10 mm Hg. Art. or more were achieved in 98.8% of patients in the NPL group and 98.4% of patients in the IDP group.

The quality of life

Studying quality of life is an important aspect of assessing therapy. Analysis of VAS data at the beginning of the study revealed a significantly lower quality of life in the NPL group. After 8 weeks of observation, the quality of life significantly improved in both groups, but in the NPL group this improvement was more pronounced (Table 2).

. Change in quality of life according to VAS, points.

Subjective assessment of therapy

Patients rated therapy tolerability as excellent and good in 79% (NPL group) and 80.4% of cases (HPL group; p = 0.7). Improved well-being was noted by 95% of patients in the NPL group and 94.2% in the IDP group (p = 0.3). Well-being did not change (according to the subjective assessment of patients) in 5% of cases in the NDP group and in 5.8% in the IDP group. 90.1% of patients in the NPL group and 89.7% in the IDP group expressed a desire to continue felodipine therapy.

Adverse reactions noted during observation in patients are presented in Fig. 3. The most common symptoms observed were swelling of the legs, headache and facial flushing, which is consistent with the data of other authors [7].

Dynamics of adherence to therapy during treatment

During treatment, a significant increase in the proportion of patients who answered positively to the Morisky–Green test was noted. Moreover, in the group with initially low adherence the dynamics were more pronounced (Table 3).

. Dynamics of the number of patients with a positive answer to the Morisky-Green test during the study.

When analyzing the NPL group, it was noted that 1085 patients were non-compliant and remained so. At the same time, 1656 patients showed increased adherence to therapy at the final visit (according to the Morisky-Green test). In the IDP group, only 56 patients became less compliant, and 1724 patients remained highly compliant.

In the present study, of 4816 patients, only 31% were adherent to therapy. This practically coincides with the results of the Epoch-AG study (26.5%) [8] and is somewhat less than the figures given in the WHO report [9] – 40%. We analyzed factors that could influence adherence to therapy in this cohort of patients. The analysis included gender, age, presence of coronary artery disease and diabetes, duration of hypertension, smoking status, lifestyle, drug therapy (ACEI, ARB, ACB, aspirin), and the ability to measure blood pressure at home (having a tonometer at home).

As in the literature [1, 4, 10], women were more adherent to therapy (p < 0.0001). Adherence decreased with age (p < 0.004), which also corresponds to generally accepted ideas [4, 10]. Risk factors such as smoking and sedentary lifestyle were also associated with low levels of adherence (p < 0.0002 and p < 0.003, respectively). The addition of coronary artery disease and diabetes, on the contrary, significantly increases patient adherence to treatment (p < 0.0001), making them, apparently, finally realize the seriousness of the problem.

The presence of a home blood pressure monitor and the ability to independently monitor blood pressure levels also determined increased adherence to drug therapy (p < 0.03). This fact is confirmed by foreign authors [11, 12]. The ability to independently control blood pressure makes the patient an active participant in the treatment process and allows him to see its results with his own eyes. This makes taking medications more meaningful, hence increasing adherence. The very fact of purchasing a tonometer already indicates awareness of the existing problem.

An analysis of medications used by patients was carried out. It has been shown that patients taking ARBs, i.e., drugs that have a fairly high cost, are most adherent to therapy. Nevertheless, they currently occupy first place in terms of duration of retention on therapy among antihypertensive drugs. The leading position of these drugs is associated not so much with high efficiency, but with a favorable range of side effects [13, 14], and tolerability of treatment is the leading reason for “retention” or refusal of therapy.

We paid special attention to such a parameter as DLO. When assessing the basic model adjusted for sex and age, the contribution of DLO to treatment adherence was very high (Table 4). The presence of the drug in the DLO list and its dispensing to the patient significantly increase adherence to treatment (p < 0.0001). However, with the gradual inclusion in the analysis of such parameters as the presence of coronary artery disease, the addition of diabetes mellitus to coronary artery disease, and the presence of a home blood pressure monitor, we see a gradual decrease in the contribution of DLO to adherence to therapy.

. Contribution of DLO to treatment adherence.

Thus, the presence of a drug on the DLO list is not an independent and determining factor in adherence to treatment. If the patient is properly motivated, he will buy the medicine regardless of whether it is on the list. In this case, the effectiveness and safety of the drug comes to the fore.

Our data indicate the high effectiveness of felodipine. Two-month therapy led to a good hypotensive effect in the vast majority of patients. More than 98% of patients who completed the study either achieved the target blood pressure level or reduced it by more than 20 and 10 mm Hg. Art. (SBP and DBP respectively). The data obtained are consistent with the results of other studies [15], including studies using the original felodipine [16]. Tolerability of therapy was rated by patients as excellent or good in more than 80% of cases. There was a significant improvement in quality of life, more pronounced in the NPL group. Improvement in well-being was noted by more than 90% of patients in both groups. 90.1% of patients in the NPL group and 89.7% in the IDP group expressed a desire to continue therapy with Felodip.

Noteworthy is the fact that in the NPL group the effectiveness of treatment was as high as in the IDP group. Blood pressure levels at the last visit did not differ significantly between groups. This fact can be explained by the improvement in compliance in the NPL group. The majority of patients in this group (56.2%) became adherent to treatment by the end of follow-up (p = 0.001). Thus, we see that, on the one hand, the effectiveness, good tolerability and convenience of taking felodipine (“a good drug”) contributed to increased adherence.

On the other hand, increased adherence (“a good patient”) contributed to the effectiveness of therapy. What is the cause, what is the effect, is not so important. It is only worth noting that “a good drug” is apparently not the only reason for increased adherence. An important role was played by the formation of closer contact between the patient and the doctor during the study. It should be borne in mind that the doctor’s very attention to the problem of compliance, the corresponding questioning of the patient and the assessment of this indicator over time contribute to its increase [17].

conclusions

- A pronounced hypotensive effect when using felodipine in patients with hypertension was noted both during the dose selection period and during subsequent observation.

- During long-term therapy with felodipine, a significant improvement in compliance was noted in the group of patients with NPL.

- Male gender and older age are associated with lower adherence to therapy. The presence of a home blood pressure monitor in patients with coronary artery disease and diabetes, on the contrary, is associated with higher adherence.

- The presence of a drug on the DLO list is not an independent and determining factor in increasing treatment adherence.

- Felodipine can be recommended for widespread use in outpatient practice due to its effectiveness, good tolerability and positive effect on patient compliance.

Information about the authors: Tatyana Veniaminovna Fofanova – Candidate of Medical Sciences, senior researcher at the scientific dispensary department of the ICC named after. A.L. Myasnikov FGU RKNPK MHSR. Email; Smirnova Maria Dmitrievna – Candidate of Medical Sciences, junior researcher at the scientific and dispensary department of the ICC named after. A.L. Myasnikov FGU RKNPK MHSR. Tel., e-mail; Ageev Fail Taipovich – Doctor of Medical Sciences, head of the scientific and dispensary department of the ICC named after. A.L. Myasnikov FGU RKNPK MHSR. Email; Kadushina Elena Borisovna – psychoneurologist of the scientific and dispensary department of the ICC named after. A.L. Myasnikov FGU RKNPK MHSR. Patrusheva Irina Fedorovna – Candidate of Medical Sciences, senior researcher at the scientific and dispensary department of the ICC named after. A.L. Myasnikov FGU RKNPK MHSR. Kuzmina Alla Evgenievna – Candidate of Medical Sciences, senior researcher at the scientific and dispensary department of the ICC named after. A.L. Myasnikov FGU RKNPK MHSR. Deev Alexander Dmitrievich – Candidate of Physical and Mathematical Sciences, Head of the Biostatistics Laboratory of the State Research Center for Preventive Medicine.

Drug interactions Felodip

The hypotensive effect of Felodip is enhanced by other antihypertensive drugs (beta-adrenergic receptor blockers, ACE inhibitors, diuretics), tricyclic antidepressants, and alcohol. When using Felodip, β-adrenergic receptor blockers and organic nitrates, the antianginal effect of these drugs is summed up. When used simultaneously with NSAIDs Felodip, the antihypertensive effect of Felodip is not reduced. Inhibitors of microsomal enzymes (cimetidine, erythromycin, ranitidine, ketoconazole, itraconazole, ritonavir, saquinavir, quinidine) increase the concentration of felodipine in the blood plasma, therefore the prescribed dose of Felodipine should be reduced when used simultaneously with this group of drugs. Inducers of microsomal enzymes (for example, phenytoin, carbamazepine, rifampicin and barbiturates) can reduce the concentration of felodipine in the blood plasma, so the dose of Felodipine should be adjusted when these drugs are used in combination. When Felodip is used simultaneously with digoxin, the concentration of the latter increases, but no change in the dose of Felodip is required. Significant binding of felodipine to plasma proteins does not affect the particle free fractions of another drug, which is also characterized by significant binding to plasma proteins (for example, warfarin). Grapefruit juice, due to the presence of a flavonoid in it, increases the plasma level and bioavailability of felodipine, so it cannot be used together with Felodipine.

Felodip overdose, symptoms and treatment

Symptoms: arterial hypotension and bradycardia. Treatment: the stomach is washed, activated carbon is used, and the patient is subsequently placed in an intensive observation room to monitor the function of the cardiovascular and respiratory systems. In case of severe arterial hypotension, it is necessary to place the patient in a horizontal position with the lower limbs raised upward, increase the volume of blood plasma by administering a physiological solution of sodium chloride, glucose, dextran; introduce sympathomimetics: norepinephrine, mesaton, dopamine, dobutamine, as well as calcium chloride. In case of bradycardia, AV block of II–III degree, or the appearance of asystole, atropine sulfate, norepinephrine or calcium chloride is administered intravenously. If necessary and if indicated, an artificial pacemaker is used.