An increase in monocytes in the analysis causes concern for patients. Experienced doctors know that the content of only one type of blood cell cannot make any conclusion about the state of health. There are no clear answers to the question of why some cells are increased and others are decreased.

Any changes in blood tests are used as an addition to the symptoms of the disease and are taken into account in differential diagnosis and treatment.

To understand when and in what ways elevated levels of monocytes cause pathology in the body, we need to remember the role of these cells in supporting health.

Basic functions of monocytes

Increased level of monocytes in the blood

Monocytes are single-celled mature leukocytes, formed in the bone marrow, their life expectancy does not exceed three days. In the bloodstream they reach their most active state. Here they grow, function, and after about 70 hours they degenerate into macrophages, after which they penetrate into nearby tissues.

Protective and cleansing – this is their main function. Moving along the blood stream, they find foreign bodies such as cancer cells, infections, viruses, parasites and try to destroy them. To do this, the cell gets close to the detected problem, envelops it with its body, neutralizes it and removes it from the body. In the same way, monocytes destroy bacteria, dead cells and other substances that pollute the human body.

Macrophages act on the same principle, but they take longer to destroy harmful cells.

Monocytes also take part in the synthesis of interferon, which makes cells immune to the virus, thereby enhancing the body’s protective functions.

Thus, an increase in the content of monocytes means that there is a disease that the body is fighting hard against by increasing protective cells.

Elevated monocytes - what can they mean?

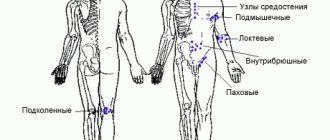

A condition in which monocytes exceed the norm is called monocytosis. The presence of a large number of monocytes in the blood can have various reasons. Therefore, when interpreting the result, all parameters of morphology and blood smear should be taken into account.

High monocytes may indicate:

- Bacterial infections, for example, tuberculosis, syphilis, subacute endocarditis;

- Parasitic infections, such as rickettsia;

- Lymphomas and leukemias (high levels of monocytes occur in myelomonocytic or monocytic leukemia);

- Myelodysplastic syndromes, multiple myelomas;

- Ovarian cancer, stomach and breast cancer or cancer metastases;

- Sarcoidosis, ulcerative enteritis, Crohn's disease;

- Collagen diseases: systemic visceral lupus, rheumatoid arthritis.

Monocytosis is also a consequence of chronic use of high doses of corticosteroids.

What else do the monocyte results show? Too many monocytes in the blood or higher than normal levels of monocytes for a longer period of time may indicate the healing process of infections.

Blood test results

How is the level of monocytes in the blood determined?

In order to determine the number of monocytes contained in the blood, it is enough to take a general blood test. Monocytes are a type of leukocyte, calculated by a laboratory assistant using a special leukocyte formula. There are two indicators of monocytes:

- Absolute quantity

– designated as “monocytes abs” or “monocytes mono”, the average number of cells per 1 μl (microliter) is taken into account.

- Relative quantity

– designated as “value” ppm/l, calculated as a percentage

Analyzes for monocytes and blood monocyte norms

Monocytes are determined in blood tests, where they are one of the elements of the leukocyte system. Most often this is a MON (MONO) blood test. The MONO morphology result is expressed as an absolute numerical value. The analysis results form also shows the percentage of monocytes relative to leukocytes.

In addition, a blood smear analysis is performed to qualitatively assess the patient’s condition.

The norm of monocytes depends on age and is:

- 1-4 years: 0.05-1.1x10⁹/l (2-7% leukocytes);

- 4-18 years: 0-0.8×10⁹/l (2-7% leukocytes);

- adults: 0-0.8×10⁹/l (1-8% leukocytes

Monocyte tests are performed on an empty stomach, 12 hours after the last meal. If you do not follow a fasting diet, the monocyte test result will be elevated.

When is it necessary to see a doctor and take an OAC test?

There are no specific signs indicating that monocytes are elevated. But at the same time, monocytosis is accompanied by other diseases, the symptoms of which can indirectly suggest changes in the number of leukocytes.

You should consult a doctor and get tested if:

- Decreased or complete loss of appetite.

- Increased fatigue and causeless weakness.

- Aversion to meat dishes.

- Sudden weight loss.

- Insomnia and drowsiness.

- Irritation, apathy, nervous breakdowns.

- Increased psycho-emotional excitability.

- Loud motility of the gastrointestinal tract.

- Constant feeling of anxiety.

- Unexplained pain in the abdomen.

- Panic attacks.

- The appearance of foamy stools.

- Stool disorders.

- The appearance of pain in joints and muscles.

- Bloody impurities in the stool.

- The appearance of acne on the mucous membranes.

- Skin rashes.

- The presence of a long dry cough with bloody sputum.

- Rashes and redness on the genitals, as well as in case of heavy discharge from the genital tract.

- Discomfort and pain during sexual intercourse.

Elevated monocytes in a child - what do monocytes above normal mean?

Elevated monocytes in a child are most often a consequence of infection or ongoing inflammatory processes, for example, this condition is typical for:

- childhood mononucleosis;

- ascariasis, enterobiasis and other helminthic infestations;

- scarlet fever;

- tuberculosis.

High monocyte counts are also observed during teething.

Very often, monocytes increase during the recovery period after infection. In this case, monocytosis may persist for several weeks. Unless the condition is accompanied by alarming changes in morphology or blood smear, there is no cause for concern.

A child's monocyte count above normal can also be a harbinger of more serious diseases, such as leukemia or lymphoma.

Both slightly elevated and significantly higher than normal monocytes require mandatory medical consultation. Monitoring elevated monocytes is imperative during pregnancy, which may indicate the development of inflammation.

Deviations and normal values

In the period from birth to the age of 16 years, the norms of monocytes in the blood change. Absolute values generally decrease, in contrast to relative values, which up to 16 years of age can either decrease or increase.

| Person's age | Norm of MON parameters |

| In a newborn | 3-12% |

| First two weeks of life | The indicator increases to 5-12% |

| By the year | Decreases 4-10% |

| By 2 years | Is 3-10% |

| From 3 to 16 years old | The lower limit remains 3%, and the upper limit is reduced to 1% |

| From 16 years to old age | from 3-11% |

Absolute indicators from birth to 16 years should decrease, initially ranging from 1.9-2.4 million/l, ultimately decreasing to 0.004-0.08 million/l

A reduced level of monocytes in the blood is called monocytopenia, an increased level is called monocytosis.

The focus of inflammation and an increased level of monocytes in the transcript will be designated as mono. Absolute monocytosis is an increase in the absolute number of monocytes.

The percentage change in monocytes relative to the total number of leukocytes is called relative monocytosis. From time to time, this indicator may increase as a percentage for various reasons, for example, a very hearty breakfast. That is why minor deviations from the norm have no diagnostic value.

But an increase in white cells in the range of 13-17% may indicate a focus of inflammation, and an indicator of 18-24% indicates a serious infectious-inflammatory process.

Dietary recommendations

During the period of treatment, as well as rehabilitation, the patient should adhere to several rules related to diet. Compliance with them will have a beneficial effect on the patient’s condition.

- Reduce your sugar intake. Diabetes and high blood glucose levels are associated with an increase in the release of monocytic volume, the onset of inflammation. It is wise to reduce refined sugar from your diet to reduce your risk of developing cardiovascular disease. Along with obesity and insulin resistance, they are often caused by eating foods with a high glycemic index that contain refined sugar and processed foods.

- Stop drinking alcohol. Alcohol-containing drinks stimulate the inflammatory process, aggravating the patient's well-being. It is a big misconception that a small dose of alcohol has a beneficial effect on the quality of appetite - in cancer patients or patients with diseases of the gastrointestinal tract, this can cause a number of complications.

- Include fish in your diet. Omega-3 fatty acids are found in fatty fish such as salmon and mackerel. It is advisable to include these foods in your diet. Fish oil has anti-inflammatory properties that provide protection against atherosclerosis and heart disease. Taking it as a supplement can reduce inflammation caused by the activation of monocytes.

- Mediterranean diet. Monounsaturated fats, found in olive oil, seeds, nuts, vegetables, fruits and whole grains, are part of the widespread Mediterranean diet. These products have a protective effect against inflammatory reactions caused by monocytes.

To identify the disease at an early stage, you need to systematically undergo a medical examination. A clinical blood test, which involves a routine diagnostic program for a person’s condition, will reflect an accurate picture of his health. And the detected increase in monocytes will be the reason for a comprehensive examination and treatment.

Causes of increased monocytes

Absolute monocytosis can develop in an adult in the following cases:

- For chronic intestinal diseases such as Crohn's disease, ulcerative colic, inflammation of the small intestine.

- Severe chronic diseases: rheumatoid or psoriatic arthritis, lupus erythematosus.

- Poisoning with substances containing: phosphorus, chlorine or their compounds.

- Infections with infectious diseases: brucellosis, syphilis, salmonellosis, tuberculosis, chickenpox, dysentery, rubella, influenza, whooping cough.

- Rheumatological diseases.

- Rheumatism, endocarditis.

- Blood diseases: chronic myeloid leukemia, osteomyelofibrosis, polycythemia, thrombocytopenic purpura, acute leukemia.

- The development of sepsis or the presence of purulent foci.

- Penetration of parasites and viruses into the body.

- Injury

- Malignant neoplasms of the lymphatic system: lymphoma, lymphogranulomatosis.

- Myocardial infarction.

- Development of fungal diseases.

Also, an excess of the norm of monocytes is observed in patients during the postoperative period and during the recovery period after infectious diseases. Lack of sleep, stress, a rich meal before taking the test, and excessive physical activity can cause an increase in monocytes. Therefore, it is necessary to take this data into account when taking the OAC.

In men

There are no specific reasons for increasing the level of monocytes in men. Men who often experience stress, work a lot, and work is closely related to mental stress and excessive nerves can suffer from monocytosis.

Among women

Elevated monocytes in a woman’s body indicate the presence of infectious diseases, as well as various inflammatory processes. The norms of leukocyte deviation do not depend on gender, however, in women, unlike men, monocytes can increase due to the characteristics of the reproductive system: during menstruation or ovulation, this is associated with a hormonal surge.

In pregnant women

During pregnancy and lactation, the level of leukocytes is especially important for a woman’s body. This is due to the fact that now the protective function must be performed not only for the matter, but also for the fetus inside it, and after the baby is born, they help the woman regain strength faster. During pregnancy, a restructuring of the immune and endocrine systems occurs in a woman’s body, and hormonal levels often change, so the ratio of all types of leukocytes changes.

The level of lower monocytes in the first trimester of pregnancy drops to 1%. But after just a few weeks it increases again to 3%, this figure remains until the last trimester, in which, due to changes in hormonal levels in connection with the body’s preparation for childbirth, the level of monocytes may increase. Immediately after childbirth, the level drops, but later rises again, which means that the body has begun to recover after childbirth.

In children

The normal levels of monocytes in the blood of children are higher than those of adults; the highest levels are observed in newborns. However, there is nothing to worry about if the age norms are not exceeded or the deviation level is not higher than 10%. An increase in this indicator may indicate the presence of infectious or viral diseases or infection with helminths. Often the reason for an increase in leukocyte levels can be the replacement of baby teeth with molars, this is associated with the formation of new tissues.

Also, an increase in monocytes may be associated with hereditary factors, the postoperative period and the presence of more severe diseases, for example, leukemia. It is worth noting that children often experience a low level of leukocytes (monocytopenia) than monocytosis; this is more dangerous and may indicate exhaustion of the body and weak resistance to harmful factors.

When is monocytosis not dangerous?

A harmless moderate increase in monocytes can occur against the background of a decrease in lymphocytes and eosinophils. Similar situations are possible with a severe allergic reaction, in the initial stage of childhood viral acute infections (whooping cough, scarlet fever, chicken pox, measles).

An allergic reaction to the skin is accompanied by monocytosis

Significant death of other immune cells occurs. Therefore, the body produces more phagocytes for compensatory purposes to close the gap in protection.

After 2–3 days, with an uncomplicated course of the disease, the required level of eosinophils and lymphocytes is restored. Elevated monocytes during the recovery period are even considered a positive prognostic sign.

Why is an increase in monocytes dangerous?

An increase in monocytes in the body in most cases indicates the presence of pathology. When an infectious disease appears, the body begins a stubborn fight against it by additionally producing white cells to actively fight the disease. It seems that the more monocytes, the better, because this way you can quickly cope with the disease. In fact, there is a downside, since an excessive amount of them can itself provoke inflammation.

Large accumulations of white bodies in the vessels can:

- Disrupt blood flow.

- Strengthen atherosclerosis.

- Reduce blood flow to the heart muscle.

- Cause damage to the vessel wall.

An extensive study of the qualitative and quantitative composition of blood, which provides characteristics of red blood cells and their specific indicators (MCV, MCH, MCHC, RDW), leukocytes and their varieties in percentage (leukocyte formula) and platelets.

Microscopy of the leukocyte formula is always performed as part of the analysis.

English synonyms

Complete blood count (CBC) with differential.

Research method

- SLS (sodium lauryl sulfate) - method

- Conductometric method

- Microscopy

- Flow cytometry

What biomaterial can be used for research?

Venous, capillary blood.

How to properly prepare for research?

- Eliminate alcohol from your diet for 24 hours before the test.

- Children under 1 year of age should not eat for 30-40 minutes before the test.

- Children aged 1 to 5 years should not eat for 2-3 hours before the test.

- Do not eat for 8 hours before the test; you can drink clean still water.

- Avoid physical and emotional stress for 30 minutes before the test.

- Do not smoke for 30 minutes before the test.

General information about the study

A clinical blood test with a leukocyte formula is one of the most frequently performed tests in medical practice. Today, this study is automated and allows you to obtain detailed information about the quantity and quality of blood cells: red blood cells, leukocytes and platelets. From a practical point of view, the doctor should primarily focus on the following parameters of this analysis:

- Hb (hemoglobin) – hemoglobin;

- MCV (mean corpuscular volume) – average volume of an erythrocyte;

- RDW (RBC distribution width) – distribution of red blood cells by volume;

- total number of red blood cells;

- total platelet count;

- total leukocyte count;

- leukocyte formula - the percentage of different leukocytes: neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils and basophils.

Determining these parameters makes it possible to diagnose conditions such as anemia/polycythemia, thrombocytopenia/thrombocytosis and leukopenia/leukocytosis, which can either be symptoms of a disease or act as independent pathologies.

When interpreting the analysis, the following features should be taken into account:

- In 5% of healthy people, blood test results deviate from the accepted reference values. On the other hand, the patient may show a significant deviation from his usual indicators, which at the same time remain within the accepted norms. For this reason, test results must be interpreted in the context of each individual's individual normal performance.

- Blood counts vary by race and gender. Thus, in women the number and quality characteristics of red blood cells are lower, and the number of platelets is higher than in men. For comparison: men – Hb 12.7-17.0 g/dl, erythrocytes 4.0-5.6×1012/l, platelets 143-332×109/l, women – Hb 11.6-15.6 g /dl, red blood cells 3.8-5.2×1012/l, platelets 169-358×109/l. In addition, hemoglobin, neutrophils and platelets are lower in dark-skinned people than in white people.

What is the research used for?

- For diagnosis and control of treatment of many diseases.

When is the study scheduled?

- During a preventive examination;

- if the patient has complaints or symptoms of any disease.

What do the results mean?

Reference values

| Component | Floor | Age | Reference values |

| White blood cells (WBC), *10^9/l | 0-1 year | 6.0 — 17.5 | |

| 1-2 years | 6.0 — 17.0 | ||

| 2-4 years | 5.5 — 15.5 | ||

| 4-6 years | 5.0 — 14.5 | ||

| 6-10 years | 4.5 — 13.5 | ||

| 10-16 years | 4.5 — 13.0 | ||

| More than 16 years | 4.0 — 10.0 | ||

| Red blood cells (RBC), *10^12/l | female | 0-14 days | 3.9 — 5.9 |

| male | 0-14 days | 3.9 — 5.9 | |

| male | 1-4 months | 3.5 — 5.1 | |

| female | 1-4 months | 3.5 — 5.1 | |

| male | 4-6 months | 3.9 — 5.5 | |

| female | 4-6 months | 3.9 — 5.5 | |

| male | 6-9 months | 4.0 — 5.3 | |

| female | 6-9 months | 4.0 — 5.3 | |

| male | 9-12 months | 4.1 — 5.3 | |

| female | 9-12 months | 4.1 — 5.3 | |

| male | 1-3 years | 3.8 — 4.8 | |

| female | 1-3 years | 3.8 — 4.8 | |

| male | 3-6 years | 3.7 — 4.9 | |

| female | 3-6 years | 3.7 — 4.9 | |

| male | 6-9 years | 3.8 — 4.9 | |

| female | 6-9 years | 3.8 — 4.9 | |

| male | 9-12 years | 3.9 — 5.1 | |

| female | 9-12 years | 3.9 — 5.1 | |

| male | 12-15 years | 4.1 — 5.2 | |

| female | 12-15 years | 3.8 — 5.0 | |

| male | 15-18 years old | 4.2 — 5.6 | |

| female | 15-18 years old | 3.9 — 5.1 | |

| male | 18-45 years old | 4.3 — 5.7 | |

| female | 18-45 years old | 3.8 — 5.1 | |

| male | 45-65 years | 4.2 — 5.6 | |

| female | 45-65 years | 3.8 — 5.3 | |

| male | More than 65 years | 3.8 — 5.8 | |

| female | More than 65 years | 3.8 — 5.2 | |

| female | 14-30 days | 3.3 — 5.3 | |

| male | 14-30 days | 3.3 — 5.3 | |

| Hemoglobin (HGB), g/l | male | 0-14 days | 134 — 198 |

| female | 0-14 days | 134 — 198 | |

| male | 14-30 days | 107 — 171 | |

| female | 14-30 days | 107 — 171 | |

| male | 1-2 months | 94 — 130 | |

| female | 1-2 months | 94 — 130 | |

| male | 2-4 months | 103 — 141 | |

| female | 2-4 months | 103 — 141 | |

| male | 4-6 months | 111 — 141 | |

| female | 4-6 months | 111 — 141 | |

| male | 6-9 months | 114 — 140 | |

| female | 6-9 months | 114 — 140 | |

| male | 9-12 months | 113 — 141 | |

| female | 9-12 months | 113 — 141 | |

| male | 1-5 years | 110 — 140 | |

| female | 1-5 years | 110 — 140 | |

| male | 5-10 years | 115 — 145 | |

| female | 5-10 years | 115 — 145 | |

| male | 10-12 years | 120 — 150 | |

| female | 10-12 years | 120 — 150 | |

| male | 12-15 years | 120 — 160 | |

| female | 12-15 years | 115 — 150 | |

| male | 15-18 years old | 117 — 166 | |

| female | 15-18 years old | 117 — 153 | |

| male | 18-45 years old | 132 — 173 | |

| female | 18-45 years old | 117 — 155 | |

| male | 45-65 years | 131 — 172 | |

| female | 45-65 years | 117 — 160 | |

| male | More than 65 years | 126 — 174 | |

| female | More than 65 years | 117 — 161 | |

| Hematocrit (HCT), % | male | 0-14 days | 41 — 65 |

| female | 0-14 days | 41 — 65 | |

| male | 14-30 days | 33 — 55 | |

| female | 14-30 days | 33 — 55 | |

| male | 1-2 months | 28 — 42 | |

| female | 1-2 months | 28 — 42 | |

| male | 2-4 months | 32 — 44 | |

| female | 2-4 months | 32 — 44 | |

| male | 4-6 months | 31 — 41 | |

| female | 4-6 months | 31 — 41 | |

| male | 6-9 months | 32 — 40 | |

| female | 6-9 months | 32 — 40 | |

| male | 9-12 months | 33 — 41 | |

| female | 9-12 months | 33 — 41 | |

| male | 1-3 years | 32 — 40 | |

| female | 1-3 years | 32 — 40 | |

| male | 3-6 years | 32 — 42 | |

| female | 3-6 years | 32 — 42 | |

| male | 6-9 years | 33 — 41 | |

| female | 6-9 years | 33 — 41 | |

| male | 9-12 years | 34 — 43 | |

| female | 9-12 years | 34 — 43 | |

| male | 12-15 years | 35 — 45 | |

| female | 12-15 years | 34 — 44 | |

| male | 15-18 years old | 37 — 48 | |

| female | 15-18 years old | 34 — 44 | |

| male | 18-45 years old | 39 — 49 | |

| female | 18-45 years old | 35 — 45 | |

| male | 45-65 years | 39 — 50 | |

| female | 45-65 years | 35 — 47 | |

| male | More than 65 years | 37 — 51 | |

| female | More than 65 years | 35 — 47 | |

| Mean erythrocyte volume (MCV), fL | female | 0-12 months | 71 — 112 |

| male | 0-12 months | 71 — 112 | |

| female | 1-5 years | 73 — 85 | |

| male | 1-5 years | 73 — 85 | |

| female | 5-10 years | 75 — 87 | |

| male | 5-10 years | 75 — 87 | |

| female | 10-12 years | 76 — 94 | |

| male | 10-12 years | 76 — 94 | |

| female | 12-15 years | 73 — 95 | |

| female | 15-18 years old | 78 — 98 | |

| female | 18-45 years old | 81 — 100 | |

| female | 45-65 years | 81 — 101 | |

| female | More than 65 years | 81 — 102 | |

| male | 12-15 years | 77 — 94 | |

| male | 15-18 years old | 79 — 95 | |

| male | 18-45 years old | 80 — 99 | |

| male | 45-65 years | 81 — 101 | |

| male | More than 65 years | 81 — 102 | |

| Avg. sod. hemoglobin in er-te (MCH), pg | female | 0-14 days | 30 — 37 |

| male | 0-14 days | 30 — 37 | |

| female | 14-30 days | 29 — 36 | |

| male | 14-30 days | 29 — 36 | |

| female | 1-2 months | 27 — 34 | |

| male | 1-2 months | 27 — 34 | |

| female | 2-4 months | 25 — 32 | |

| male | 2-4 months | 25 — 32 | |

| female | 4-6 months | 24 — 30 | |

| male | 4-6 months | 24 — 30 | |

| female | 6-9 months | 25 — 30 | |

| male | 6-9 months | 25 — 30 | |

| female | 9 months — 1 g. | 24 — 30 | |

| male | 9 months — 1 g. | 24 — 30 | |

| female | 1-3 years | 22 — 30 | |

| male | 1-3 years | 22 — 30 | |

| female | 3-6 years | 25 — 31 | |

| male | 3-6 years | 25 — 31 | |

| female | 6-9 years | 25 — 31 | |

| male | 6-9 years | 25 — 31 | |

| female | 9-15 years | 26 — 32 | |

| male | 9-15 years | 26 — 32 | |

| female | 15-18 years old | 26 — 34 | |

| male | 15-18 years old | 27 — 32 | |

| female | 18-45 years old | 27 — 34 | |

| male | 18-45 years old | 27 — 34 | |

| female | 45-65 years | 27 — 34 | |

| male | 45-65 years | 27 — 35 | |

| female | More than 65 years | 27 — 35 | |

| male | More than 65 years | 27 — 34 | |

| Avg. conc. hemoglobin in air (MCHC), g/l | 0-1 years | 290 — 370 | |

| 1-3 years | 280 — 380 | ||

| 3-12 years | 280 — 360 | ||

| 12-19 years old | 330 — 340 | ||

| More than 19 years | 300 — 380 | ||

| Distribution erith. along V - standard deviation (RDW-SD), fL | 37 — 54 | ||

| Distribution erith. according to V - coefficient. Variance (RDW-CV), % | More than 6 months | 11.6 — 14.8 | |

| 0-6 months | 14.9 — 18.7 | ||

| female | 0-10 days | 99 — 421 | |

| male | 0-10 days | 99 — 421 | |

| female | 10-30 days | 150 — 400 | |

| male | 10-30 days | 150 — 400 | |

| female | 1-6 months | 180 — 400 | |

| male | 1-6 months | 180 — 400 | |

| female | 6 months — 1 g. | 160 — 390 | |

| male | 6 months — 1 g. | 160 — 390 | |

| female | 1-5 years | 150 — 400 | |

| male | 1-5 years | 150 — 400 | |

| female | 5-10 years | 180 — 450 | |

| male | 5-10 years | 180 — 450 | |

| female | 10-15 years | 150 — 450 | |

| male | 10-15 years | 150 — 400 | |

| female | More than 15 years | 150 — 400 | |

| male | More than 15 years | 150 — 400 | |

| Distribution platelet count by volume (PDW), fL | 10 — 20 | ||

| Mean platelet volume (MPV), fL | 9.4 — 12.4 | ||

| Large platelet ratio (P-LCR), % | 13 — 43 | ||

| Neutrophils (NE), 10^9/l | 0-4 years | 1.5 — 8.5 | |

| 4-8 years | 1.5 — 8.0 | ||

| 8-16 years | 1.8 — 8.0 | ||

| More than 16 years | 1.8 — 7.7 | ||

| Lymphocytes (LY), *10^9/l | 0-1 years | 2.0 — 11.0 | |

| 1-2 years | 3.0 — 9.5 | ||

| 2-4 years | 2.0 — 8.0 | ||

| 4-6 years | 1.5 — 7.0 | ||

| 6-8 years | 1.5 — 6.8 | ||

| 8-10 years | 1.5 — 6.5 | ||

| 10-16 years | 1.2 — 5.2 | ||

| More than 16 years | 1.0 — 4.8 | ||

| Monocytes (MO), *10^9/l | 0-1 years | 0.05 — 1.1 | |

| 1-2 years | 0.05 — 0.6 | ||

| 2-4 years | 0.05 — 0.5 | ||

| 4-16 years | 0.05 — 0.4 | ||

| More than 16 years | 0.05 — 0.82 | ||

| Eosinophils (EO), *10^9/l | 0-1 years | 0.05 — 0.4 | |

| 1-6 years | 0.02 — 0.3 | ||

| More than 6 years | 0.02 — 0.5 | ||

| Basophils (BA), *10^9/l | 0 — 0.08 | ||

| Neutrophils, % (NE%), *10^9/l | 0-1 years | 16 — 45 | |

| 1-2 years | 28 — 48 | ||

| 2-4 years | 32 — 55 | ||

| 4-6 years | 32 — 58 | ||

| 6-8 years | 38 — 60 | ||

| 8-10 years | 41 — 60 | ||

| 10-16 years | 43 — 60 | ||

| More than 16 years | 47 — 72 | ||

| Lymphocytes, % (LY%) | 0-1 years | 45 — 75 | |

| 1-2 years | 37 — 60 | ||

| 2-4 years | 33 — 55 | ||

| 4-6 years | 33 — 50 | ||

| 6-8 years | 30 — 50 | ||

| 8-10 years | 30 — 46 | ||

| 10-16 years | 30 — 45 | ||

| More than 16 years | 19 — 37 | ||

| Monocytes, % (MO%) | 0-1 years | 4 — 10 | |

| 1-2 years | 3 — 10 | ||

| More than 2 years | 3 — 12 | ||

| Eosinophils, % (EO%) | 0-1 years | 1 — 6 | |

| 1-2 years | 1 — 7 | ||

| 2-4 years | 1 — 6 | ||

| More than 4 years | 1 — 5 | ||

| Basophils,% (BA%) | female | 0 — 1.2 | |

| male | 0 — 1.2 | ||

| Neutrophils, 10^9/l | 0-4 years | 1.5 — 8.5 | |

| 4-8 years | 1.5 — 8.0 | ||

| 8-16 years | 1.8 — 8.0 | ||

| More than 16 years | 1.8 — 7.7 | ||

| Lymphocytes, *10^9/l | 0-1 years | 2.0 — 11.0 | |

| 1-2 years | 3.0 — 9.5 | ||

| 2-4 years | 2.0 — 8.0 | ||

| 4-6 years | 1.5 — 7.0 | ||

| 6-8 years | 1.5 — 6.8 | ||

| 8-10 years | 1.5 — 6.5 | ||

| 10-16 years | 1.2 — 5.2 | ||

| More than 16 years | 1.0 — 4.8 | ||

| Monocytes, *10^9/l | 0-1 years | 0.05 — 1.1 | |

| 1-2 years | 0.05 — 0.6 | ||

| 2-4 years | 0.05 — 0.5 | ||

| 4-16 years | 0.05 — 0.4 | ||

| More than 16 years | 0.05 — 0.82 | ||

| Eosinophils, *10^9/l | 0-1 years | 0.05 — 0.4 | |

| 1-6 years | 0.02 — 0.3 | ||

| More than 6 years | 0.02 — 0.5 | ||

| Basophils, *10^9/l | 0 — 0.08 | ||

| Neutrophils: rods. (%) | 0 — 5 | ||

| Neutrophils: segment. (SEG%) | 0-1 years | 16 — 45 | |

| 1-2 years | 28 — 48 | ||

| 2-5 years | 32 — 55 | ||

| 5-7 years | 38 — 58 | ||

| 7-8 years | 41 — 60 | ||

| 8-12 years | 43 — 60 | ||

| 12-16 years old | 45 — 60 | ||

| More than 16 years | 47 — 72 | ||

| Lymphocytes, % (LY%) | 0-1 years | 45 — 75 | |

| 1-2 years | 37 — 60 | ||

| 2-4 years | 33 — 55 | ||

| 4-6 years | 33 — 50 | ||

| 6-8 years | 30 — 50 | ||

| 8-10 years | 30 — 46 | ||

| 10-16 years | 30 — 45 | ||

| More than 16 years | 19 — 37 | ||

| Monocytes, % (MO%) | 0-1 years | 4.0 — 10 | |

| 1-2 years | 3.0 — 10 | ||

| More than 2 years | 3.0 — 12 | ||

| Eosinophils, % (EO%) | 0-1 years | 1 — 6 | |

| 1-2 years | 1 — 7 | ||

| 2-4 years | 1 — 6 | ||

| More than 4 years | 1 — 5 | ||

| Basophils,% (BA%) | female | 0 — 1 | |

| male | 0 — 1 |

Interpretation of the analysis:

Anemia

A decrease in hemoglobin and/or red blood cells indicates the presence of anemia. Using the MCV indicator, you can perform a primary differential diagnosis of anemia:

- MCV less than 80 fl (microcytic anemia). Causes: iron deficiency anemia;

- thalassemia;

- anemia of chronic disease;

- sideroblastic anemia.

Considering that the most common cause of microcytic anemia is iron deficiency, when identifying microcytic anemia, it is recommended to determine the concentration of ferritin, as well as serum iron and total serum iron-binding capacity. It is recommended to pay attention to the RDW indicator (increased only in iron deficiency anemia) and platelet count (often increased in iron deficiency anemia).

- MCV 80-100 fl (normocytic anemia). Causes:

- bleeding;

- anemia in chronic renal failure - chronic renal failure;

- hemolysis;

- anemia due to iron or vitamin B12 deficiency.

To exclude hidden bleeding, a stool test for occult blood is recommended. To exclude iron or vitamin B12 deficiency as a cause of normocytic anemia, determine iron and vitamin B12 in the blood. To exclude chronic renal failure, tests for creatinine and blood urea are performed. To exclude hemolytic anemia - tests for haptoglobin, LDH, indirect bilirubin and reticulocytes.

- MCV more than 100 fl (macrocytic anemia). Causes:

- alcohol abuse;

- medications (hydroxyurea, zidovudine);

- deficiency of vitamin B12 and folic acid.

Marked macrocytosis (MCV greater than 110 fl) usually indicates a primary bone marrow disease.

To exclude vitamin B12 deficiency as a cause of macrocytic anemia, homocysteine and vitamin B12 tests are performed.

Thrombocytopenia

Causes:

- thrombocytopenic purpura/hemolytic-uremic syndrome;

- DIC syndrome (disseminated intravascular coagulation);

- drug thrombocytopenia (co-trimoxazole, procainamide, thiazide diuretics, heparin);

- hypersplenism;

- idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura.

For the differential diagnosis of diseases occurring with thrombocytopenia, a coagulogram, an analysis for HIV infection, antinuclear antibodies and blood protein electrophoresis may also be required.

It should be remembered that in pregnant women, platelets can normally decrease to 75-150×109/l.

Leukopenia

For the differential diagnosis of leukopenia, both the absolute number of each of the 5 main lineages of leukocytes and their percentage (leukocyte formula) are important.

Neutropenia. A decrease in neutrophils of less than 0.5 × 109/l is severe neutropenia. Causes:

- congenital agranulocytosis (Kostmann syndrome);

- drug neutropenia (carbamazepine, penicillins, clozapine and others);

- infections (sepsis, viral infection);

- autoimmune neutropenia (SLE, Felty's syndrome).

Lymphopenia. Causes:

- tuberculosis.

- chronic renal failure;

- autoimmune lymphopenia (SLE, rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis);

- viral infection (HIV);

- drug-induced lymphopenia (glucocorticosteroids, monoclonal antibodies);

- acquired variable immunodeficiency;

- congenital lymphopenia (Bruton agammaglobulinemia, severe combined immunodeficiency, DiGeorge syndrome);

Polycythemia

Increase in Hb and/or Ht concentration and/or red blood cell count:

- polycythemia vera is a myeloproliferative disease; in the blood test, in addition to erythrocytosis, thrombocytosis and leukocytosis are observed;

- relative polycythemia (bone marrow compensatory response to hypoxia in COPD or ischemic heart disease; excess erythropoietin in renal cell carcinoma).

For the differential diagnosis of polycythemia, a study of erythropoietin levels is recommended.

Thrombocytosis

Causes:

- primary thrombocytosis (malignant disease of the myeloid lineage of the bone marrow, including essential thrombocytosis and chronic myeloid leukemia);

- secondary thrombocytosis after removal of the spleen, during an infectious process, iron deficiency anemia, hemolysis, trauma and malignant diseases (reactive thrombocytosis).

An increase in Hb, MCV, or total leukocyte count suggests primary thrombocytosis. The degree of thrombocytosis, as a rule, does not allow differential diagnosis of primary and secondary thrombocytosis, since even a very significant increase in platelets (more than 1000 × 109 l) can also be observed with reactive thrombocytosis. Additional tests may also be recommended: blood ferritin and C-reactive protein.

Leukocytosis

The first step in interpreting leukocytosis is to evaluate the leukocyte count. Leukocytosis can be caused by an excess of immature leukocytes (blasts) in acute leukemia or mature, differentiated leukocytes (granulocytosis, monocytosis, lymphocytosis).

Granulocytosis - neutrophilia. Causes:

- leukemoid reaction (reactive neutrophilia in the presence of infection, inflammation, use of certain medications);

- myeloproliferative disease (eg, chronic myelogenous leukemia).

An increase in the percentage of band neutrophils of more than 6% indicates the presence of infection, but can also be observed in chronic myeloid leukemia and other myeloproliferative diseases.

Granulocytosis - eosinophilia. Causes:

- primary eosinophilia (hypereosinophilic myeloproliferative syndrome);

- secondary eosinophilia (parasitosis, helminthiasis, allergies, vasculitis, lymphoma).

Additional tests will depend on your medical history, but should at a minimum include a stool test for helminth eggs.

Granulocytosis - basophilia. Causes:

- chronic basophilic leukemia.

Monocytosis. Causes:

- myeloproliferative disease, such as CML;

- reactive monocytosis (chronic infections, granulomatous inflammation, radiation therapy, lymphoma).

Lymphocytosis. Causes:

- reactive lymphocytosis (viral infection); Virus-specific laboratory tests are recommended;

- lymphocytic leukemia (acute and chronic).

A clinical blood test with a leukocyte formula is a screening method that can be used to preliminarily assess the state of bone marrow function and suspect or exclude many diseases. This analysis, however, does not always make it possible to establish the cause of the changes, the identification of which, as a rule, requires additional laboratory tests, including pathomorphological and histochemical studies. The most accurate information can be obtained by dynamic monitoring of changes in blood parameters.