General information

Vasculitis (a synonym for this name is the term angiitis ) is the name for a heterogeneous group of diseases, the basis of which is an immunopathological inflammatory process affecting the blood vessels. It affects different vessels - arteries, arterioles, veins, venules, capillaries. The consequence of this disease is changes in the functions and structure of the organs that the affected vessels supply with blood. The disease can provoke bleeding, necrosis , and ischemia .

Scientists are still conducting research, trying to more accurately determine vasculitis - what kind of disease it is, and what reasons lead to its development. The exact causes of the disease are still not known. It is assumed that the disease develops due to the influence of external factors in combination with a genetic disposition. There is also evidence that the disease can be caused by hepatitis virus or Staphylococcus aureus . The ICD-10 code is I77.6.

Necrotic-ulcerative

Another type of polymorphic dermal angiitis is the necrotic-ulcerative type, which forms a special type of blood clots in the affected vessels, causing necrosis of both individual areas of the skin and the entire skin with the further formation of a black scab. This type of disease is characterized by a severe course with a sudden onset and a sharp deterioration in the patient’s general condition, which can lead to death. Even if the patient does not die, hard-to-heal ulcers form on the affected areas of the skin, which are very difficult to treat.

Pathogenesis

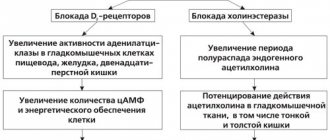

Work is still underway to study the etiology of systemic vasculitis. In particular, there is an opinion about the likely role of bacterial or viral infection in its development. The pathogenesis of the disease is complex, including a number of immune mechanisms. The following factors are believed to play a role in the development of systemic vasculitis:

- The formation in the body of autoantibodies to antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, during which activation and adhesion of neutrophils to endothelial cells occurs, which leads to their damage.

- Formation of autoantibodies to antigens .

- Formation of pathogenic immunocomplexes and their deposition into the vascular wall. Which affects polymorphonuclear leukocytes after complement activation. In turn, they produce lysosomal enzymes that damage the vascular wall. Its permeability increases. thrombosis often occurs .

- Immune system reactions associated with the action of T lymphocytes . This mechanism is decisive in the development of Wegener's granulomatosis . Due to interaction with the antibody, sensitized T-lymphocytes produce lymphokines that inhibit the migration of macrophages. Next, they concentrate them where antigens accumulate. Macrophages are activated and produce lysosomal enzymes, which leads to damage to the vascular walls. These mechanisms lead to the manifestation of granuloma.

- The direct influence of various infectious agents on the vascular wall.

- Vasospastic and coagulation disorders.

- Effects resulting from the release of inflammatory mediators and cytokines.

- Processes of interaction between leukocytes and endothelial cells, resulting in the release of a large number of reformed and newly synthesized adhesive molecules.

- The appearance of antibodies to phospholipids. Such antibodies are found in patients with systemic vasculitis. Their cross-reaction with endothelial proteins is noted, which leads to an increase in the coagulating properties of the blood.

Classification

First of all, vasculitis is divided into primary and secondary .

- Primary lesions are an independent process in which the vessels become inflamed. Their cause is unknown.

- Secondary are lesions that develop as complications of ongoing infectious or oncological diseases. The cause of such diseases can also be the use of drugs, the influence of toxins , and infectious agents.

Vasculitis photo

In turn, primary vasculitis, taking into account the size of the inflamed vessels, is divided into the following groups:

- Inflammatory process of small vessels: Wegener's granulomatosis , hemorrhagic vasculitis (Henoch-Schönlein purpura), cryoglobulinemic vasculitis , microscopic polyangiitis , hypocomplementary urticarial vasculitis , Churg-Strauss syndrome , hypersensitivity vasculitis.

- Inflammatory process of medium vessels: Kawasaki disease , periarteritis nodosa .

- Inflammatory process of large vessels: giant cell arteritis , Takayasu disease .

- Inflammation of vessels of different sizes: Behçet's disease , vasculitis in Cogan's syndrome .

- Inflammation in systemic diseases: lupus, sarcoidosis, rheumatoid vasculitis.

- Vasculitis of individual organs: primary angiitis of the central nervous system, cutaneous arteritis , isolated aortritis , cutaneous leukocyte-clastic angiitis , others.

Isolated cutaneous vasculitis is also isolated. It can be a manifestation of the following diseases:

- Henoch-Schönlein hemorrhagic vasculitis;

- hypersensitivity allergic vasculitis;

- nodular vasculitis;

- erythema nodosum;

- periarteritis nodosa .

Depending on the caliber of the affected vessels, where exactly they are localized and the type of lesion, a certain clinical picture is present.

The secondary form of vasculitis may be as follows:

- associated with syphilis ;

- with hepatitis B ;

- with hepatitis C ;

- with cancer;

- immune complex, associated with drugs;

- ANCA drug-associated vasculitis;

- other.

Since systemic vasculitis is determined by immune mechanisms, then, depending on the type of immunopathological process, systemic primary vasculitis is divided into the following groups:

- Those associated with immune complexes: lupus and rheumatoid vasculitis, Behçet's disease , hemorrhagic vasculitis , cryoglobulinemic vasculitis .

- Those associated with organ-specific antibodies : Kawasaki disease.

- Those associated with antineurophilic cytoplasmic antibodies: microscopic polyarteritis , Wegener's granulomatosis , classical polyarteritis nodosa , Churg-Strauss syndrome .

Treatment of vasculitis

Treatment of vasculitis in adults and children depends entirely on the form of the disease and the causes that caused it. A number of patients at the Yauza Clinical Hospital undergo extracorporeal hemocorrection, which not only improves the patient’s condition, but also corrects the functioning of the immune system.

Therapeutic measures

Treatment of vasculitis in our clinic, including hemorrhagic, is aimed at achieving the following goals:

- elimination of clinical signs of pathology;

- reducing the risk of complications;

- preventing damage to vital organs;

- complete recovery of the patient or achievement of stable long-term remission.

To do this, our specialists - rheumatologist, dermatologist, allergist - develop an individual treatment regimen for each patient, which includes:

- bed rest for at least 3 weeks;

- avoiding contact with allergens;

- diet therapy;

- prescribing enterosorbents, antihistamines, antispasmodics, hemostatic agents and antiplatelet agents;

- in some cases, the use of hormones and cytostatics is justified.

To reduce the destructive influence of circulating immune complexes and enhance the effectiveness of drug therapy, patients with severe forms of vasculitis are treated with extracorporeal hemocorrection methods.

Physiotherapeutic methods for treating vasculitis

Plasmapheresis has proven its effectiveness. The physiotherapeutic procedure is aimed at improving kidney function and preventing the development of renal failure. Extracorporeal methods of blood purification are effective in combination with intravenous administration of immunoglobulins.

The most significant therapeutic effect can be achieved if harmful substances are concentrated in the liquid component of the bloodstream. Before the procedure, precise dosing of the amount of VCP (volume of circulating plasma) is necessary.

Drug treatment

Medicines are prescribed individually, depending on the characteristics of the patient’s body and the form of the disease:

- giant cell arteritis - GC (glucocorticosteroids) and pulse therapy with methylprednisolone, as well as leflunomide, methotrexate, genetic engineering therapy with drugs such as tocilizumab;

- Takayasu arteritis – glucocorticosteroids, basic anti-inflammatory drugs (methotrexate, etc.), genetic engineering therapy (tocilizumab);

- polyarteritis nodosa - GK until a clinical effect is achieved, then in a maintenance dose in combination with azathioprine or cyclophosphamide;

- Wegener's granulomatosis - for dysfunction of the upper respiratory tract, biseptol is prescribed (helps cope with the infection). Treatment can be carried out with GC, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide (it always pulses first); rapid progression requires pulse therapy, also rituximab;

- Churg-Strauss syndrome – GC with dose reduction and cytostatics, genetic engineering therapy.

In any case, it is necessary to prescribe drugs that improve blood flow, suppress the immune system and relieve inflammation. If necessary, the patient is referred to other specialists.

Hemorrhagic vasculitis - treatment with hemocorrection methods

EG is indicated at the very beginning of clinical manifestations. Early treatment with hemocorrection methods effectively prevents the development of serious complications and allows for rapid and long-term remission of the disease, which has a beneficial effect on the patient’s ability to work and his quality of life.

Advantages of EG methods

This treatment method allows:

- reduce activity or quickly stop the pathological process and, thereby, reduce the risk of complications in hemorrhagic vasculitis from the kidneys, joints,

- accelerate the disappearance of clinical manifestations of the skin, kidneys, gastrointestinal tract, joints, etc., including in the treatment of vasculitis on the legs,

- improve blood supply to affected organs,

- increase the body's sensitivity to medications, including hormonal drugs, allowing their dosage to be reduced (even to the point of discontinuation).

The following methods of extracorporeal hemocorrection are indicated for the treatment of vasculitis:

- cryoapheresis;

- cascade plasma filtration;

- immunosorption;

- high-volume plasma exchange;

- extracorporeal pharmacotherapy;

- photopheresis

Indications for EG are: the presence of vascular lesions confirmed by biopsy, abdominal syndrome, ineffectiveness of drug therapy, side effects or complications when using drugs.

Causes

Until now, the causes of the development of this disease have not been studied enough. The causes of the manifestation of the primary form of the disease are determined only tentatively. It can develop due to viral and chronic infections, allergies , chronic autoimmune diseases, taking certain medications and contact with chemicals. The factors that provoke this disease are hypothermia, burns, radiation, trauma, and hereditary factors. However, these phenomena are not the causes of the disease, but its triggering factors.

Symptoms of vasculitis

Common clinical symptoms for vasculitis of all types are undulating fever , in which body temperature rises during outbreaks of vascular damage. Skin-hemorrhagic and muscular-articular syndrome are also noted. The peripheral nervous system may also be involved in the pathological process. This leads to the development of polyneuritis. There is also exhaustion and multifaceted visceral lesions.

In the specialized literature, the term “ vasculopathy ” is sometimes used to define signs of vascular damage in this disease.

In general, the symptoms of systemic vasculitis, depending on the type, can be varied and affect different systems and organs. The following manifestations are possible:

- Skin - rashes, ulcers appear, fingers turn blue, ulcers may form in the genital area, gangrene .

- Lungs - shortness of breath , coughing, spitting up blood, episodes of suffocation are possible.

- Nervous system – headache, dizziness , convulsions, impaired sensitivity and motor function, strokes .

- Mucous membranes - the appearance of rashes and ulcers.

- Kidneys – increased blood pressure , swelling.

- Digestive system - diarrhea , abdominal pain, blood in the stool.

- Musculoskeletal system - swelling and pain in the joints, muscle soreness.

- Vision - pain and pain in the eyes, blurred vision, redness of the eyes.

- Heart and blood vessels - cardiac dysfunction, chest pain, blood pressure surges.

- ENT organs - deterioration of smell and hearing, discharge from the ears and nose, hoarse voice, nosebleeds.

Hemorrhagic vasculitis

Photo of vasculitis on the legs

This form is mostly benign. Typically, remission or recovery occurs within a few weeks. However, hemorrhoidal vasculitis can be complicated by damage to the intestines or kidneys. Most often, with this form of the disease, damage to the skin develops. A person is affected by a hemorrhagic rash - palpable purpura , which is faintly visible, but can be identified by touch. At the very beginning of the disease, vasculitis appears on the legs - the rash is localized in the distal parts of the lower extremities, and then moves to the thighs and buttocks.

Also with this form of the disease, articular syndrome is observed. The large joints of the legs are most often affected. Migrating pain in the joints is noted at the time when skin rashes appear. Some patients may experience abdominal syndrome, in which the gastrointestinal tract is affected. In this case, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and gastrointestinal bleeding are noted. Renal syndrome is also possible.

Cutaneous

With this type of disease, small or medium-sized vessels of the dermis are affected. However, the vessels of the internal organs are not affected. The symptoms of this type of disease are similar to those of a number of skin diseases. In particular, capillary effusions, capillary damage, nodules, and urticaria . If this form accompanies systemic diseases, the patient is also concerned about joint pain and increased body temperature.

Allergic vasculitis

Photos of symptoms of allergic vasculitis

With this form, the patient exhibits erythematous and hemorrhagic spots, rashes, and nodules. A skin infarction is likely when a black crust forms in the area of the rash. At the sites of the rash, burning pain or itching appears. There are hemorrhages under the nails on the toes, muscles and joints hurt. Characteristic signs of the disease can be seen in the photo of allergic vasculitis.

Most often, with this form of vasculitis, a rash appears on the thighs, feet, and legs. If the disease becomes generalized, rashes on the torso and forearms may be bothersome.

This group includes acute and chronic erythema nodosum , erythema induratum of Bazin , temporal angiitis , and Behçet's disease .

The most important symptoms of Behçet's disease are recurrent stomatitis and ulcers on the genitals. Behcet's syndrome also affects the mucous membrane of the eyes and skin. The characteristic symptoms of this type of disease are the formation of ulcers and erosions.

Photo of Behçet's disease

In patients with acute erythema nodosum, large nodules appear, and the color of the skin underneath them changes from red to greenish.

Systemic vasculitis

Speaking about systemic vasculitis - what kind of disease it is, it should be noted that this form of the disease develops in the event of a violation of immune mechanisms in people with a variety of systemic diseases with connective tissue lesions.

With the development of Wegener's granulomatosis, the disease is manifested by the following symptoms: destructive changes in the respiratory tract, vascular walls and kidneys develop; ulcerated granulomas appear on the mucous membranes of the mouth, nose, and bronchi; glomerulonephritis develops . The disease leads to severe complications - internal organs, nervous system, visual organs, and skin suffer.

Autoimmune vasculitis in rheumatism spreads to the body as a whole. Its manifestations depend on the stage of development. An autoimmune type of disease affects the skin, blood vessels of internal organs and the brain. The likelihood of internal bleeding increases.

Cryoglobulinemic vasculitis

This is a type of systemic form of the disease, which is characterized by the appearance of cryoglobulin . They are deposited on the walls of blood vessels and gradually destroy them. A characteristic sign of this disease, which has a progressive form, is damage to peripheral nerves and gradual loss of sensitivity. If treatment is not started promptly, this disease can cause motor paralysis and loss of speech.

Urticarial vasculitis

Photo of urticarial vasculitis

This type of disease is one of the varieties of the allergic form, in which chronic inflammation of the superficial vessels of the skin develops. At the very beginning, such patients are often diagnosed with “chronic urticaria”. The disease progresses in waves. A person develops hemorrhagic nodules, blisters, and spots on the skin. He often feels a burning sensation in the affected areas. The temperature rises, pain in the lower back, joints, muscles, abdomen, and headache. The temperature rises and glomerulonephritis develops.

Periarteritis nodosa

It develops mainly in males. I am worried about muscle pain, weight loss, and fever. Sometimes nausea and vomiting and severe pain in the abdomen appear sharply. The disease can lead to strokes and mental disorders.

Takayasu's disease (nonspecific aortoarteritis)

Takayasu arteritis is a progressive granulomatous inflammatory process of the aorta and its main branches. Nonspecific aortoarteritis (Takayasu's disease) mainly affects young women. About half of patients who develop arteritis suffer from primary physical symptoms. They develop fever, insomnia , fatigue, weight loss, and joint pain. Often nonspecific aortoarteritis leads to the development of anemia and increased ESR.

In approximately half of the patients, preliminary somatic symptoms do not develop, and only late changes in the vascular system are noted. During the development of the disease in its later stages, due to the weakness of the vessel walls, localized aneurysms can develop. The disease also provokes the development of Raynaud's phenomenon . Therefore, it is important that treatment is started as early as possible and that the treatment protocol for patients with Takayasu's disease is strictly followed.

Wegener's granulomatosis

This form causes pain in the paranasal sinuses, ulcers on the nasal mucosa, and ulcerative necrotic rhinitis . Destruction of the nasal septum may occur, leading to a saddle nose deformity. kidney failure develops rapidly shortness of breath , and coughing up blood are noted

Churg-Strauss syndrome

This disease is also called eosinophilic granulomatosis with angiopathy. During its development, blood vessels are affected, as a result of which the blood supply to vital organs deteriorates. The most common symptom of Churg-Strauss vasculitis is asthma . However, in addition to it, other symptoms also appear: fever, rash, bleeding in the gastrointestinal tract, pain in the feet and hands. Sometimes the symptoms are mild, while in other cases severe, life-threatening symptoms develop.

Polymorphic dermal angiitis

Angiitis of the skin photo

This is angiitis, in which chronic recurrent dermatosis develops due to a nonspecific inflammatory process in the walls of skin vessels. During the development of the disease, the skin of the legs is predominantly affected. But rashes can appear in other places. Sometimes their appearance is preceded by general symptoms - fever, weakness, headache. The rash does not go away for several months. After recovery, there is a risk of relapse. There are many varieties of this disease depending on the characteristics of the rash.

Livedo angiitis

It mainly develops in women during puberty. Initially, persistent livedo-cyanotic spots appear on the legs. They appear less frequently in other places. The spots can have different sizes and shapes. When cooled, the severity increases. Over time, small ulcers, necrosis, and hemorrhages may develop at the spots. Patients are concerned about chilliness, pain in the legs, and painful ulcers.

Cerebral vasculitis

A serious disease characterized by the development of an inflammatory process in the walls of blood vessels in the brain. The cerebral form of this disease can provoke hemorrhages and tissue necrosis. As the disease progresses, the patient may experience severe headaches. Epileptic paroxysm and focal neurological deficit are possible. During the development of the disease, one of the following complexes of symptoms is likely to occur:

- multifocal manifestations resembling the clinical picture of multiple sclerosis ;

- acute encephalopathy with mental disorders;

- symptoms characteristic of a brain mass.

Microscopic vasculitis

This form mainly affects small vessels. It is rare and can begin as pulmonary-renal syndrome, which is accompanied by rapidly progressing glomerulonephritis and alveolar hemorrhages . At the very beginning of the disease, general manifestations develop: fever, myalgia, arthralgia, weight loss. Other symptoms depend on which organs and systems are affected. Most often, damage occurs to the kidneys, less often to the skin, respiratory system, and gastrointestinal tract.

Giant cell temporal arteritis

The disease affects older people. Its symptoms are weakness, undulating fever, malaise, severe throbbing headaches, and swelling in the temples.

Urticarial vasculitis: a modern approach to diagnosis and treatment

Urticarial vasculitis/angiitis (UV) is a skin disease characterized by the appearance of blisters with the histological features of leukocytoclastic vasculitis, persisting for more than 24 hours and often resolving with residual effects [1]. The exact prevalence of the disease in Russia and in the world is unknown [2]. Among patients with chronic urticaria, the incidence of HC is 5–20% [3–6]. The pathogenesis of the disease is mediated by the formation and deposition of immune complexes in the walls of blood vessels, activation of the complement system and degranulation of mast cells due to the action of anaphylotoxins C3a and C5a. There are normocomplementary and hypocomplementary forms of HF, as well as a rare syndrome of hypocomplementary HF, which is regarded as a variant of systemic lupus erythematosus [2, 7]. In patients with hypocomplementemia, the disease is usually more severe [8]. All forms of HF, especially hypocomplementary ones, can be accompanied by systemic symptoms (for example, angioedema, pain in the abdomen, joints and chest, uveitis, Raynaud's phenomenon, symptoms resulting from damage to the lungs and kidneys, etc.) [7, 9].

Clinical manifestations

The classic manifestations of HS include blisters (Fig. 1), which are accompanied by burning, pain, tension and, rarely, itching and persist for more than 24 hours (usually 3-5 days, which can be confirmed by circling the rash with a pen or marker and follow-up ). Angioedema (corresponding to the involvement of deep vessels of the skin) occurs in approximately 42% of patients [10], more often in patients with hypocomplementary HF syndrome [11]. Giant urticaria (> 10 cm) appear less frequently than in urticaria.

The rashes are localized on any areas of the body, but more often on areas of the skin subject to pressure. When resolved, they leave behind residual hyperpigmentation, which is better determined by diascopy or dermatoscopy.

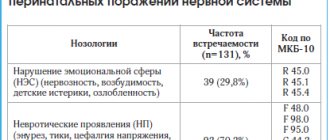

Systemic symptoms include fever, malaise, and myalgia. Certain organs may be involved: lymph nodes, liver, spleen, kidneys, gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts, eyes, central nervous system, peripheral nerves and heart (Table).

Damage to joints in HF is more common than damage to other organs; appears in half of patients with HF [10] mainly in the form of migrating and transient peripheral arthralgia in the area of any joints, in 50% of patients with hypocomplementary HF syndrome [15] - in the form of severe arthritis, which is not typical for normocomplementary HF. Renal involvement usually manifests as proteinuria and microscopic hematuria, defined as glomerulonephritis and interstitial nephritis, and occurs in 20–30% of patients with hypocomplementemia [10]. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and bronchial asthma occur in 17–20% of patients with hypocomplementary HF syndrome and in 5% with normocomplementary HF [10]. Possible gastrointestinal symptoms include nausea, abdominal pain, vomiting and diarrhea, which occur in 17–30% of patients with HF [15]. Ophthalmological complications occur in 10% of patients with HF and in 30% of patients with hypocomplementary HF syndrome. As a rule, this is conjunctivitis, episcleritis, iritis or uveitis [16].

Diagnostics

The examination of patients with HF consists of a history, physical examination, laboratory tests and additional consultations with specialists if necessary (rheumatologist, nephrologist, pulmonologist, cardiologist, ophthalmologist and neurologist). It is important to identify systemic symptoms. To do this, for example, if damage to the respiratory tract is suspected, a chest x-ray, pulmonary function tests and/or bronchoalveolar lavage are performed.

Laboratory tests may include measuring antinuclear antibodies, complement components, and cryoglobulins in the blood, as well as a complete blood count and kidney function tests. ESR is often elevated, but does not serve as a specific indicator and is not associated with the severity of HF or the presence of systemic involvement. Hypocomplementemia, as mentioned earlier, is an important marker of systemic disease and a high likelihood of complications.

Optimal confirmation of EF based on serum complement component measurements requires determination of C1q, C3, C4, and CH50 levels 2 or 3 times over several months of follow-up [17]. Detection of anti-C1q can help in the diagnostic search and confirm the diagnosis of hypocomplementary HC.

Cryoglobulinemia is the most well-known and studied syndrome in some patients with hepatitis C and HC [18]. Cryoglobulins are immunoglobulins that precipitate at temperatures below 37 °C and are responsible for the development of systemic vasculitis, characterized by the deposition of immune complexes in small and medium-sized blood vessels [18]. These proteins are detected in 50% of HCV-infected individuals, although symptoms associated with cryoglobulinemia are detected in less than 15% of patients [19] and include HF as well as peripheral neuropathy [20]. Treatment is aimed at the underlying HCV infection.

In most cases of HF, the cause of the disease is not determined. Normocomplementary HF acts as an idiopathic disease in many patients, while in others it is associated with monoclonal gammopathy, neoplasia, and sensitivity to ultraviolet radiation or cold [17].

When collecting an anamnesis, it is necessary to clarify the duration of preservation of individual elements, the presence of pain or burning in the area of the rash (itching with urticaria is less common than with chronic urticaria), the presence of residual effects (for example, hyperpigmentation) and associated symptoms. For differential diagnosis and confirmation of diagnosis, a skin biopsy [1] and referral of the patient for consultation with related specialists may be required.

Skin biopsy is the “gold standard” for diagnosing UV. Skin biopsies stained with hematoxylin and eosin usually show the characteristic histopathological features of vasculitis, which include most of the features of leukocytoclastic vasculitis:

- damage and swelling of endothelial cells, destruction or occlusion of the vascular wall;

- release of red blood cells from the vascular bed into the surrounding tissues (extravasation), leukoclasia or karyorrhexis (disintegration of the nuclei of granular leukocytes, leading to the formation of nuclear “dust”), fibrin deposition in and around the vessels, fibrinoid necrosis of venules;

- perivascular infiltration consisting mainly of neutrophils, although in “old” lesions leukocytes and eosinophils may dominate. Sometimes an increase in the number of TCs is observed.

Treatment

HC treatment is selected depending on the presence/absence of systemic symptoms, the extent and severity of the skin process and the previous response to therapy. The goal of therapy is to achieve long-term control using minimally toxic doses of drugs. There is no single standardized approach to treating the disease yet. We tried to systematize the treatment data given below into a single algorithm for practical use (Fig. 2).

Symptomatic therapy

In patients with HC with isolated skin lesions, 1st and 2nd generation antihistamines (especially with severe itching) [13, 15] and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can be effective. The main purpose of the latter is to relieve joint pain (effective in no more than 50% of cases). In some patients, NSAIDs lead to exacerbation of heart failure [10]. It is possible to use ibuprofen up to 800 mg 3 or 4 times a day, naproxen 500 mg 2 times a day or indomethacin 25 mg 3 times a day, increasing the dose as needed to a maximum of 50 mg 4 times a day. Taking NSAIDs can cause erosive and ulcerative lesions of the gastrointestinal tract and headaches.

Mild to moderate urticarial vasculitis

For the initial treatment of patients with mild or moderate HC in the absence of systemic symptoms and life-threatening manifestations of the disease (for example, kidney and lung damage), as well as in the ineffectiveness of treatment with antihistamines and NSAIDs, glucocorticosteroids (GCS) are used in monotherapy or in combination with dapsone or colchicine . The dose of corticosteroids varies depending on the severity of the heart attack. It is recommended to begin treatment with 0.5–1 mg/kg per day (with a possible dose increase to 1.5 mg/kg per day) with an assessment of response to treatment after 1 week. The effect of therapy in most cases is observed already on days 1–2 of therapy. Once disease control is achieved, the dose of corticosteroids should be gradually reduced over several weeks to the minimally effective dose to maintain CV control.

With long-term therapy with GCS (more than 2–3 months), there is a risk of side effects, which necessitates the addition of steroid-sparing agents to reduce the dose of GCS [10], such as dapsone. The latter has been successfully used as monotherapy or in combination with GCS at a dose of 50–100 mg per day for the treatment of skin processes in HF and hypocomplementary HF syndrome [11, 21, 22]. Side effects of dapsone include headache, non-hemolytic anemia and agranulocytosis, which requires evaluation of a complete blood count during treatment. In patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, the use of the drug can cause severe hemolysis. In such patients, enzyme levels should be measured before initiating dapsone therapy [23].

As an alternative to dapsone and when its use is contraindicated, colchicine is used at an initial dose of 0.5–0.6 mg per day orally. If there is no effect within several weeks, the dose of colchicine can be increased to 1.5–1.8 mg per day. After starting treatment, it is necessary to evaluate the results of a complete blood count due to the possible development of cytopenias associated with the use of the drug [23].

Severe urticarial vasculitis

In patients with severe HF and refractory, systemic and/or life-threatening symptoms, GCS are used in combination with other drugs (in order of preference): mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, azathioprine and cyclosporine. Cyclophosphamide is rarely prescribed due to potential toxicity and lack of effectiveness. Over the past few years, there has been increasing evidence supporting the use of biological agents: rituximab, anakinra and canakinumab [2, 24–26].

Mycophenolate mofetil has been effective in the treatment of hypocomplementary HF syndrome as maintenance therapy after disease control has been achieved with corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide [24]. Recommended dosage: 0.5–1 g twice daily.

Methotrexate was useful as a steroid-sparing agent in one case [25] and caused exacerbation of HF in another [27].

Azathioprine was effectively used at a starting dose of 1 mg/kg per day in combination with prednisolone for HF with kidney and skin damage [28, 29]. If there is no effect within several weeks, the dose may be increased to the maximum recommended (2.5 mg/kg per day).

Cyclosporine A has been effective in hypocomplementary HF syndrome, especially in the renal and pulmonary complications of the syndrome [30], and also as a steroid-sparing agent [31]. The initial dose of the drug is 2–2.5 mg/kg per day. If there is no effect within several weeks, the dose can be increased to 5 mg/kg per day. The drug is nephrotoxic and may cause increased blood pressure.

Rituximab has been used in several patients with severe HF with varying efficacy [26, 32]. Anakinra was effective in patients with HF that was poorly responsive to other therapies [33]. Canakinumab was prescribed to 10 patients with HC, all of whom showed a marked improvement in the course of the disease, a decrease in the level of inflammatory markers and the absence of severe side effects [34].

Interferon A was effective both in monotherapy and in combination with ribavirin when CV was combined with hepatitis C or A [14, 35]. The effectiveness of other drugs, such as cyclophosphamide, intravenous immunoglobulin and reserpine, has been poorly studied and is shown only in isolated clinical cases [36–38].

Conclusion

HF has a chronic and unpredictable course with an average duration of 3–4 years, and in some cases up to 25 years [39]. In one study, 40% of patients experienced complete remission of the disease within 1 year [15]. Mortality is low if there are no renal or pulmonary complications. When a group of patients was observed for 12 years, most of them did not experience the development of UV-related diseases (oncological, connective tissue, etc.). In isolated cases, the evolution of UD into systemic lupus erythematosus [12, 40] and Sjögren's syndrome [41] has been reported. When a disease that has become a possible cause of vasculitis is identified, the course and prognosis of vasculitis depend on the treatment of the underlying pathology. Fatal outcomes in patients with HF can include laryngeal edema, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, respiratory failure, sepsis, renal failure and myocardial infarction [15].

There is a need for well-designed randomized placebo-controlled studies to better understand the etiology and pathogenesis of the disease, clarify the course and prognosis of different forms of HF, as well as study the effectiveness and safety of existing agents and search for new highly effective therapy.

Literature

- Zuberbier T., Aberer W., Asero R., Bindslev-Jensen C., Brzoza Z., Canonica GW, Church MK, Ensina LF, Gimenez-Arnau A., Godse K., Goncalo M., Grattan C., Hebert J., Hide M., Kaplan A., Kapp A., Abdul Latiff AH, Mathelier-Fusade P., Metz M., Nast A., Saini SS, Sanchez-Borges M., Schmid-Grendelmeier P., Simons FE , Staubach P., Sussman G., Toubi E., Vena GA, Wedi B., Zhu XJ, Maurer M. The EAACI/GA (2) LEN/EDF/WAO Guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis, and management of urticaria: the 2013 revision and update // Allergy. 2014. T. 69. No. 7. pp. 868–887.

- Kolkhir P.V., Olisova O.Yu., Kochergin N.G. Syndrome of hypocomplementary urticarial vasculitis at the onset of systemic lupus erythematosus // Bulletin of Dermatology and Venereology. 2013. No. 2. P. 53–61.

- Zuberbier T., Henz BM, Fiebiger E., Maurer D., Stingl G. Anti-FcepsilonRIalpha serum autoantibodies in different subtypes of urticaria // Allergy. 2000. T. 55. No. 10. P. 951–954.

- Natbony SF, Phillips ME, Elias JM, Godfrey HP, Kaplan AP Histologic studies of chronic idiopathic urticaria // J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1983. T. 71. No. 2. P. 177–183.

- Monroe EW Urticarial vasculitis: an updated review // J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981. T. 5. No. 1. P. 88–95.

- Warin RP Urticarial vasculitis // Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983. T. 286. No. 6382. P. 1919–1920.

- Saigal K., Valencia IC, Cohen J., Kerdel FA Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis with angioedema, a rare presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus: rapid response to rituximab // J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003. T. 49. No. 5 Suppl. pp. S283–285.

- Davis MD, Daoud MS, Kirby B., Gibson LE, Rogers RS, 3rd. Clinicopathologic correlation of hypocomplementemic and normocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis // J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998. T. 38. No. 6. Pt 1. P. 899–905.

- Jachiet M., Flageul B., Deroux A., Le Quellec A., Maurier F., Cordoliani F., Godmer P., Abasq C., Astudillo L., Belenotti P., Bessis D., Bigot A., Doutre MS, Ebbo M., Guichard I., Hachulla E., Heron E., Jeudy G., Jourde-Chiche N., Jullien D., Lavigne C., Machet L., Macher MA, Martel C., Melboucy-Belkhir S., Morice C., Petit A., Simorre B., Zenone T., Bouillet L., Bagot M., Fremeaux-Bacchi V., Guillevin L., Mouthon L., Dupin N., Aractingi S., Terrier B. The clinical spectrum and therapeutic management of hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis: data from a French national study of fifty-seven patients // Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015. T. 67. No. 2. P. 527–534.

- Mehregan DR, Hall MJ, Gibson LE Urticarial vasculitis: a histopathologic and clinical review of 72 cases // J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992. T. 26. No. 3. Pt 2. P. 441–448.

- Wisnieski JJ, Baer AN, Christensen J, Cupps TR, Flagg DN, Jones JV, Katzenstein PL, McFadden ER, McMillen JJ, Pick MA et al. Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome. Clinical and serologic findings in 18 patients // Medicine (Baltimore). 1995. T. 74. No. 1. P. 24–41.

- Bisaccia E., Adamo V., Rozan SW Urticarial vasculitis progressing to systemic lupus erythematosus // Arch Dermatol. 1988. T. 124. No. 7. P. 1088–1090.

- Callen JP, Kalbfleisch S. Urticarial vasculitis: a report of nine cases and review of the literature // Br J Dermatol. 1982. T. 107. No. 1. P. 87–93.

- Hamid S., Cruz PD, Jr., Lee WM Urticarial vasculitis caused by hepatitis C virus infection: response to interferon alfa therapy // J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998. T. 39. No. 2. Pt 1. P. 278–280.

- Sanchez NP, Winkelmann RK, Schroeter AL, Dicken CH The clinical and histopathologic spectrum of urticarial vasculitis: study of forty cases // J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982. T. 7. No. 5. P. 599–605.

- Davis MD, Brewer JD Urticarial vasculitis and hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome // Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2004. T. 24. No. 2. P. 183–213.

- Wisnieski JJ Urticarial vasculitis // Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2000. T. 12. No. 1. P. 24–31.

- Misiani R., Bellavita P., Fenili D., Borelli G., Marchesi D., Massazza M., Vendramin G., Comotti B., Tanzi E., Scudeller G. et al. Hepatitis C virus infection in patients with essential mixed cryoglobulinemia // Ann Intern Med. 1992. T. 117. No. 7. P. 573–577.

- Pawlotsky JM, Roudot-Thoraval F., Simmonds P., Mellor J., Ben Yahia MB, Andre C., Voisin MC, Intrator L., Zafrani ES, Duval J., Dhumeaux D. Extrahepatic immunologic manifestations in chronic hepatitis C and hepatitis C virus serotypes // Ann Intern Med. 1995. T. 122. No. 3. P. 169–173.

- Ferri C., La Civita L., Cirafisi C., Siciliano G., Longombardo G., Bombardieri S., Rossi B. Peripheral neuropathy in mixed cryoglobulinemia: clinical and electrophysiologic investigations // J Rheumatol. 1992. T. 19. No. 6. P. 889–895.

- Eiser AR, Singh P., Shanies HM Sustained dapsone-induced remission of hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis - a case report // Angiology. 1997. T. 48. No. 11. P. 1019–1022.

- Muramatsu C., Tanabe E. Urticarial vasculitis: response to dapsone and colchicine // J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985. T. 13. No. 6. P. 1055.

- Venzor J., Lee WL, Huston DP Urticarial vasculitis // Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2002. T. 23. No. 2. P. 201–216.

- Worm M., Sterry W., Kolde G. Mycophenolate mofetil is effective for maintenance therapy of hypocomplementaemic urticarial vasculitis // Br J Dermatol. 2000. T. 143. No. 6. P. 1324.

- Stack PS Methotrexate for urticarial vasculitis // Ann Allergy. 1994. T. 72. No. 1. P. 36–38.

- Mukhtyar C., Misbah S., Wilkinson J., Wordsworth P. Refractory urticarial vasculitis responsive to anti-B-cell therapy // Br J Dermatol. 2009. T. 160. No. 2. P. 470–472.

- Borcea A., Greaves MW Methotrexate-induced exacerbation of urticarial vasculitis: an unusual adverse reaction // Br J Dermatol. 2000. T. 143. No. 1. P. 203–204.

- Moorthy AV, Pringle D. Urticaria, vasculitis, hypocomplementemia, and immune-complex glomerulonephritis // Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1982. T. 106. No. 2. P. 68–70.

- Ramirez G., Saba SR, Espinoza L. Hypocomplementemic vasculitis and renal involvement // Nephron. 1987. T. 45. No. 2. P. 147–150.

- Soma J., Sato H., Ito S., Saito T. Nephrotic syndrome associated with hypocomplementaemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome: successful treatment with cyclosporin A // Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999. T. 14. No. 7. P. 1753–1757.

- Renard M., Wouters C., Proesmans W. Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis in a boy with hypocomplementaemic urticarial vasculitis // Eur J Pediatr. 1998. T. 157. No. 3. P. 243–245.

- Mallipeddi R., Grattan CE Lack of response to severe steroid-dependent chronic urticaria to rituximab // Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007. T. 32. No. 3. P. 333–334.

- Botsios C., Sfriso P., Punzi L., Todesco S. Non-complementaemic urticarial vasculitis: successful treatment with the IL-1 receptor antagonist, anakinra // Scand J Rheumatol. 2007. T. 36. No. 3. P. 236–237.

- Krause K., Mahamed A., Weller K., Metz M., Zuberbier T., Maurer M. Efficacy and safety of canakinumab in urticarial vasculitis: an open-label study // J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013. T. 132. No. 3. P. 751–754, e755.

- Matteson EL Interferon alpha 2 a therapy for urticarial vasculitis with angioedema apparently following hepatitis A infection // J Rheumatol. 1996. T. 23. No. 2. P. 382–384.

- Worm M., Muche M., Schulze P., Sterry W., Kolde G. Hypocomplementaemic urticarial vasculitis: successful treatment with cyclophosphamide-dexamethasone pulse therapy // Br J Dermatol. 1998. T. 139. No. 4. P. 704–707.

- Berkman SA, Lee ML, Gale RP Clinical uses of intravenous immunoglobulins // Ann Intern Med. 1990. T. 112. No. 4. P. 278–292.

- Demitsu T., Yoneda K., Iida E., Takada M., Azuma R., Umemoto N., Hiratsuka Y., Yamada T., Kakurai M. Urticarial vasculitis with haemorrhagic vesicles successfully treated with reserpine // J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008. T. 22. No. 8. pp. 1006–1008.

- Soter NA Chronic urticaria as a manifestation of necrotizing venulitis // N Engl J Med. 1977. T. 296. No. 25. P. 1440–1442.

- Soylu A., Kavukcu S., Uzuner N., Olgac N., Karaman O., Ozer E. Systemic lupus erythematosus presenting with normocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis in a 4-year-old girl // Pediatr Int. 2001. T. 43. No. 4. P. 420–422.

- Aboobaker J., Greaves MW Urticarial vasculitis // Clin Exp Dermatol. 1986. T. 11. No. 5. P. 436–444.

P. V. Kolhir1, Candidate of Medical Sciences O. Yu. Olisova, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor

GBOU VPO First Moscow State Medical University named after. I. M. Sechenova Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, Moscow

1 Contact information

Tests and diagnostics

During the diagnostic process, the following studies are carried out:

- Blood and urine tests are carried out multiple times. In the process of such studies, in patients with vasculitis, an acceleration of ESR, an increase in fibrinogen , and an increase in C-reactive protein levels are often determined. Leukocytosis may be detected. Blood and urine tests help determine kidney damage.

- Immunogram study. In the process of immunological research, in some forms of vasculitis, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) are determined. This greatly simplifies the diagnosis.

- Allergy testing.

- Instrumental research methods - ultrasound, radiography, echocardiography, etc.

- Biopsy of the affected organ or tissue for immunohistochemical and histological examination. Such a study helps confirm the diagnosis.

But the most important thing in the diagnostic process is still the determination of ANCA in blood serum by the method of indirect immunofluorescence or by enzyme immunoassay.

The set of studies that the doctor prescribes depends on the clinical picture and the patient’s complaints.

Doctors often encounter difficulties at the stage of early diagnosis, since the symptoms of the disease are often not clearly expressed and are also similar to the signs of other diseases. Therefore, differential diagnosis often causes certain difficulties. For example, with hemorrhagic vasculitis, abdominal syndrome sometimes appears, which can be perceived as a gastrointestinal disease requiring surgical intervention.

To correctly establish a diagnosis, the following algorithm is practiced:

- Determination of clinical signs of vasculitis . When vascular damage occurs, skin syndrome, trophic disorder syndrome, and ischemic syndrome develop; mucosal involvement, arterial hypertension, venous involvement and organ changes are noted.

- Determination of laboratory and clinical signs of the disease . The presence of general symptoms and laboratory parameters is assessed.

- Distinguishing between the primary and secondary nature of the disease.

- Instrumental examination of blood vessels. To confirm vascular damage, dopplerography, angiography, biomicroscopy, angioscanning, capillaroscopy are performed and the presence of characteristic signs of damage is assessed.

- Identification of specific markers of damage to the vascular wall, laboratory diagnosis of vasculitis.

- Morphological study of material taken by biopsy. For this purpose, histochemical and immunomorphological methods are used.

- Determination of the main pathogenetic links of vascular damage. At this stage, the type of disease is determined (vasculitis associated with immune complexes; associated with ANCA; organ-specific antibodies; cell-mediated vasculitis with the formation of granulomas).

- Determination of the probable etiology of the disease. In most cases, the etiology of primary vasculitis is unknown, but exposure to certain viruses and bacteria cannot be ruled out. Immunogenetic markers are identified.

- Clarification of the form of vasculitis using classification criteria.

Diagnosis of vasculitis

Which doctor should I contact to diagnose vasculitis? First of all, you need to make an appointment with a rheumatologist. To clarify the diagnosis, a rheumatologist may involve other specialists, in particular dermatologists and immunologists.

A doctor cannot diagnose vasculitis based only on the skin manifestations of the disease. The fact is that the pathology can “masquerade” as others, so the patient needs to perform a number of tests:

- general blood analysis;

- general urine analysis;

- coagulogram;

- determination of the level of antistreptolysin-O, IGA in peripheral blood;

- determination of antibodies to hepatitis B and C (with vasculitis they are often found in the blood);

- tissue biopsy of the affected organ or body part followed by histological examination of the biopsy;

- PCR test;

- determination of antibodies to hepatitis B and C (with vasculitis they are often found in the blood);

- X-ray, ultrasound, CT or MRI (as indicated).

To make a diagnosis of hemorrhagic vasculitis, the patient must have two or more diagnostic criteria:

- specific rashes not associated with low platelet levels;

- manifestation of the disease before the age of 20 years;

- widespread abdominal pain that worsens after eating, intestinal bleeding;

- granulocytic infiltration of the walls of microvasculature vessels, which is confirmed histologically.

Treatment with folk remedies

If you visit any thematic forum, you can learn about many methods of treating vasculitis using traditional methods. But it is always important to remember that such treatment methods are only auxiliary in the process of main therapy. Before using them, it is better to consult a doctor about the advisability of such actions.

- If it is necessary to treat superficial vasculitis, herbal preparations are used that have a positive effect on the permeability of vascular walls and produce an anti-inflammatory effect. This effect is possessed by: Japanese sophora, buckwheat, water and bird knotweed, horsetail, and nettle.

- The use of decoctions and infusions of herbs that produce a general stimulating effect is also indicated: oat grains and straw, yarrow, rowan and black currant leaves, rose hips.

- The following will help reduce swelling in deep forms of vasculitis: string, stinging nettle, and cinquefoil erecta.

- In order to stimulate the function of the adrenal cortex, which is important in severe forms of vasculitis, treatment with drugs and decoctions containing ginseng, black elderberry, and eleutherococcus is recommended. Often patients are prescribed alcoholic infusions of ginseng and eleutherococcus.

- It is also recommended to drink green tea, which strengthens the walls of blood vessels and reduces their permeability, and also has a positive effect on metabolic processes in the body. It should be drunk every day, alternating with other herbal teas.

The following herbal remedies can be used:

- First collection. Knotweed, stinging nettle, sophora thick-fruited - 4 parts each, yarrow - 3 parts, black elderberry - 1 part. The infusion is prepared by pouring 5 g of the mixture with 1 cup of boiling water. Drink half a glass twice a day.

- Second collection. Black elderberry, horsetail - 3 parts each, peppermint - 2 parts. The infusion is prepared by pouring 5 g of the mixture with 1 cup of boiling water. Drink the infusion warm, half a glass 4 times a day. This infusion is also used for lotions. Applications are applied to the affected areas and kept for 15 minutes. This procedure can be carried out several times a day.

- The third gathering. is used as a general tonic and provides the body with vitamin K. To prepare it, St. John's wort, plantain, lungwort, black currant and rose hips are mixed in equal proportions. 10 g of product should be poured into 1 tbsp. water and boil for a few minutes. Drink half a glass 2 times a day.

Products for external use:

- Compresses made from pine resin. They are applied to the affected areas when applied to the skin. To prepare the product, 200 g of resin must be melted and added to it 40 g of unrefined vegetable oil, 50 g of beeswax. Mix everything, and when the mixture has cooled, apply it to the affected areas without removing it for 24 hours.

- Birch buds and nutria fat. To prepare the product you need to take 1 tbsp. grated dry or fresh birch buds and mix them with 500 g of nutria fat. Leave the product in a clay container for a week, keeping it on low heat in the oven for 3 hours every day. Place in jars and use every day as an ointment.

Treatment of polymorphic dermal angiitis

The best treatment for polymorphic dermal angiitis is the use of anti-inflammatory drugs, including butadione or indomethacin. In addition, various antihistamines (for example, suprastin or desloratadine), vitamins P and C, as well as preparations containing calcium are used. If an infection occurs against the background of polymorphic dermal angiitis, doctors prescribe antibiotic therapy. In more severe cases, glucocorticosteroid therapy is used, as well as various methods of extracorporeal hemocorrection, including plasmapheresis or cryoapheresis. In case of a recurrent course, a longer course of delagil is usually prescribed. For local treatment of polymorphic dermal angiitis, bandages with corticosteroids, as well as Flucinar or Photocort ointments, are used.

Vasculitis in children

Photos of hemorrhagic vasculitis in children

Children suffer from this disease quite rarely. But all types of vasculitis have characteristic features of their course in childhood.

Hemorrhagic vasculitis in children can occur against the background of infectious diseases - influenza , ARVI, scarlet fever , chickenpox. Other provoking factors may also influence this – hypothermia, injury, allergies, etc.

The disease leads to the fact that babies develop a lot of red hemorrhages on the mucous membranes in the mouth and lips. These hemorrhages rise slightly above the mucosa. Sometimes they bleed. A papular-hemorrhagic rash appears on the body. It forms on the limbs, legs, torso, and buttocks.

Other symptoms also appear, in particular articular syndrome. Joint pain appears simultaneously with skin manifestations or a little later. The pain disappears after a few days, but when a new rash appears, it reappears. Children also often experience abdominal syndrome , the main manifestation of which is severe abdominal pain. This can complicate the diagnosis, since the pain is similar to the symptoms of appendicitis , intestinal obstruction, etc.

Lung damage in the hemorrhagic form of the disease appears less frequently in children, but in this case there is a risk of rapid pulmonary hemorrhage. With various forms of the disease, children may experience blood in their urine.

Treatment of vasculitis must be carried out in a hospital setting. As a rule, heparin , vascular drugs, sorbents, and antiplatelet agents are prescribed. In some cases, treatment with prednisolone . When the disease progresses rapidly, plasmapheresis .

During the treatment process, adherence to a strict diet is very important. If the disease has subsided, the child is under medical supervision for 5 years. After all, there is a danger of relapse.

Introduction

Papulonecrotic angiitis (vasculitis nodularis necrotica, synonym: necrotizing nodular dermatitis of Werther-Werner-Dumling) is a polyetiological disease characterized by inflammation of the vessels of the dermis [1–3].

Despite various studies conducted in Russia [2, 3] and other countries [4-8], a single generally accepted classification of vasculitis has not been developed. In recent years, the Chapel Hill Consensus Conference (2012) classification of vasculitis has become widely used, based on the caliber of the affected vessels and the pathogenetic mechanisms of their damage [9, 10], papulonecrotic vasculitis is considered in it as leukoclastic vasculitis. In fact, this disease can be considered as a superficial form of allergic vasculitis with damage to small vessels [11]. In the occurrence of papulonecrotic vasculitis, the most important role is played by chronic infections, intolerance to certain drugs, hemodynamic disorders, immune changes, vaccination [12], etc. The literature describes cases of vasculitis after taking allopurinol, thiazide diuretics, antiepileptic drugs [13], gold drugs, antipsychotics [14], adalimumab [1], sulfonamides, penicillins, and isolated cases of angiitis during the use of ketorolac [11]. naproxen [15, 16] and ibuprofen [17]. The incidence is higher among the adult population, the onset of the disease is gradual, the course of the process is chronic with a violation of the general condition in the form of malaise, chills, fever, joint pain [5]. The rashes appear symmetrically, predominantly on the skin of the extensor surface of the upper and lower extremities, often grouping around the joints. Less commonly, the process is localized on the skin of the trunk and genitals. The most important clinical manifestation of the disease is congestive bluish-brown dense, flat or hemispherical inflammatory dermal, as well as hypodermal papules the size of a lentil or a pea, rarely larger. Along with them, sometimes as a permanent symptom, small erythematous spots with a hemorrhagic component are observed [5, 6, 8]. Most of the nodular efflorescences become necrotic: either superficial or deeper necrosis occurs, leading to ulceration [18]. The resolution of nodules usually results in small superficial atrophic and hypertrophic scars. Clinically, the disease mimics papulonecrotic tuberculosis, so the most thorough differential diagnosis should be carried out.

Pathomorphological signs are damage to arterioles and veins of small caliber with signs of arteritis, periarteritis, phlebitis, periphlebitis. Structural changes in the vascular wall are significant, accompanied by narrowing and even closure of their lumen, sometimes ending in severe necrosis. Perivascular infiltrates consist of polynuclear cells, lymphocytes and plasma cells. Sometimes a significant number of eosinophils are detected, grouped in separate foci. The cellular infiltrate can spread in a band-like manner to the subcutaneous tissue. In some cases, hemorrhages and destructive tissue changes are found. The epidermis is thickened, swollen, and in some cases intraepidermal abscesses are detected, consisting mainly of neutrophilic granulocytes [6].

We present a clinical observation.

Patient B., 59 years old, in June 2022, contacted the Moscow Research and Clinical Center for Children's Hospital, branch of the Clinic named after. V.G. Korolenko”, with a complaint of rashes on the skin of the upper and lower extremities, accompanied by burning and pain in the areas of the rashes. She considers herself sick since August 2016, when for the first time, due to uncontrolled use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs - NSAIDs (ketorolac tromethamine, metamizole sodium in tablet form) for pain in the knee joints, she noted the appearance of pain in the stomach and rashes on the skin of the chest. She did not seek medical help and did not treat herself. In December 2016, the rashes spread to the skin of the back, upper and lower extremities, when contacting a dermatologist at the place of residence, an “allergic reaction” was diagnosed and recommendations were given for treatment with desensitizing, detoxifying drugs on an outpatient basis, which led to a slight positive effect. Due to the appearance of shortness of breath, increasing edema of the lower extremities, anuria, and increased body temperature, the ambulance team was hospitalized in the nephrology department of a multidisciplinary hospital, where during the hospitalization she was consulted by a hematologist with a preliminary diagnosis of “lymphoproliferative disease, monoclonal secretion?” An oncological search was carried out including CT of the chest, abdominal cavity, esophagogastroduodenoscopy, colonoscopy, mammography - no pathological changes were found. An MRI of the pelvis revealed thickening of the endometrium. A trepanobiopsy and immunohistochemical analysis were performed - the results indicated the secondary nature of the changes. During treatment in the hospital, she was consulted by a gynecologist, a diagnostic curettage was performed with further pathomorphological examination of the material, and a fibroglandular endometrial polyp was diagnosed. It is difficult to clarify the treatment during hospitalization (discharge summary was not provided); a slight positive effect was noted. Since May 2022, rashes appeared on the skin of the lower extremities with further spread to the skin of the upper extremities; therefore, she was hospitalized in the nephrology department with a diagnosis of “Chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis.” Arterial hypertension of the III degree, stage III, risk of cardiovascular complications 4. Hypertensive nephroangiosclerosis. Bullous pemphigoid? Staphylococcal pyoderma. Chronic kidney disease C2A1 according to KDIGO. Acute interstitial nephritis (drug-induced - NSAIDs). Acute renal failure from December 2016 with restoration of kidney function. Anemia of mixed origin." During hospitalization, she was consulted by a dermatologist with a diagnosis of “Bullous pemphigoid? Lymphoma of the skin? In order to clarify the diagnosis, a pathomorphological examination of a skin biopsy was carried out, “unspecified pemphigoid” was diagnosed, the patient was sent for hospitalization to the Moscow Research and Clinical Center for Children's Hospital, branch of the Clinic named after. V.G. Korolenko."

Upon objective examination at the time of admission: the skin is diffusely xerotic, icteric with a slate tint. On the skin, mainly of the extensor surfaces of the upper (Fig. 1) and lower (Fig. 2) extremities, there are widespread polymorphic symmetrical rashes of an acute inflammatory nature, represented by a few hemorrhagic spots of a purpuric nature, prone to merging, hemispherical, in places grouped to the size of a pea by congestive cyanotic papules color, isolated edematous-infiltrated hypodermal nodes of dense elastic consistency, surrounded by a zone of perifocal inflammation in the form of a moderately edematous erythematous corolla, painless to palpation, with the crater-like formation of a necrotic scab; when it is rejected, erosive and ulcerative defects are noted, which, merging mainly in the area of the legs, form extensive lesions with an “undermined” peripheral edge, the bottom of which is made of abundant purulent-fibrinous and purulent-hemorrhagic deposits, and completely occupy the entire anatomical surface of the legs. The skin of the legs is swollen, purple-bluish in color. On the skin of the back there are post-inflammatory spots the size of a palm or more, brown in color, within which there are numerous atrophic foci of whitish scar tissue. Dermographism red. The mucous membranes are intact.

Rice. 1. Lesions on the torso and forearms.

Rice.

2. Lesions on the legs. Clinical blood test: Hb 75 g/l (normal 120-140 g/l), er. 2.63∙1012/l (norm 4.3–5.5∙1012/l); ESR 75 mm/h (normal 2-15 mm/h), single myelocytes, metamyelocytes. Biochemical blood test: C-reactive protein 182 mg/l (normal 0-10 mg/l), antistreptolysin-O 494 U/ml (normal 0-200 U/ml), alkaline phosphatase 514.9 U/l (normal 60 -325 U/l), gamma-glutamyltransferase 130.6 U/l (normal 3-38 U/l), uric acid 447 µmol/l (normal 150-350 µmol/l), urea 7.8 mmol/l ( normal 2.2-7.4 mmol/l), albumin 28.8 g/l (normal 35-52 g/l), serum iron 8 µmol/l (normal 9-30.4 µmol/l), calcium 1.90 mmol/l (normal 2.15-2.57 mmol/l).

During the stay in the hospital, for the purpose of further examination, cytosis of the cystic fluid was performed - no acantholytic cells were found, the level of eosinophils was up to 8%. According to the results of a CT scan of the chest, no focal or infiltrative changes were detected in the lungs; signs of arterial hypertension, vascular atherosclerosis, degenerative changes in the spine with symptoms of deforming spondylosis were determined.

To verify the diagnosis, a diagnostic skin biopsy was performed. In the dermis, perivascular and interstitial lymphohistiocytic infiltrates with an admixture of neutrophils, fibrinoid necrosis, infiltration of the walls of individual thin-walled vessels with neutrophils. Conclusion: histological changes are consistent with leukocytoclastic vasculitis. To determine the nosological form and exclude the systematic nature of the process, additional clinical and laboratory studies and consultation with a rheumatologist are necessary.

In the scope of therapy during hospitalization, she received vascular, detoxification, antihistamines, antibacterial drugs of the fluoroquinolone series (taking into account sensitivity), iron supplements, against the background of which a slight positive dynamics of the skin process was noted. However, taking into account the severity of the general condition due to pronounced signs of intoxication, negative dynamics of the clinical and laboratory picture, the patient was transferred to the rheumatology department of a multidisciplinary hospital, where she underwent differential diagnosis of systemic connective tissue diseases, systemic vasculitis, lymphoproliferative diseases, and an infectious process was excluded. Due to severe shortness of breath, cough, increased D-dimer level to 1742 ng/ml (normal range 0-232 ng/ml), angiopulmonography was performed; no data indicating pulmonary embolism were obtained; severe pulmonary hypertension and a focus of pulmonary tissue compaction were noted in the middle lobe of the right lung, quantitative hilar and axillary lymphadenopathy. She was consulted by a phthisiatrician; at the time of the examination, no evidence of active pulmonary tuberculosis was found. Leukopenia up to 2.8∙109/l was noteworthy, presumably due to the use of antibacterial and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Due to splenomegaly, hypergammaglobulinemia, ESR increased to 110 mm/h, an increase in the level of C-reactive protein to 20.60 mg/l/ml, skin lesions, the patient was consulted by a hematologist, ultrasound of the lymph nodes, trephine biopsy, and immunohistochemical study were performed, according to the results of which no pathological abnormalities were identified. Based on the results of echocardiography, no data indicating infective endocarditis were obtained. Bacteriological culture for the sterility of blood, urine, and wound discharge did not show any growth of microflora. Based on the presence of ulcerative defects, increased levels of laboratory markers of inflammation, the results of a diagnostic skin biopsy, the lack of clinical and instrumental data indicating other systemic vasculitis, undifferentiated vasculitis, skin lesions (ulcerative necrotic changes), lesions of the reticular system (hilar and axillary lymphadenopathy) were diagnosed , splenomegaly), blood system (Coombs-negative anemia, leukopenia), lungs (focal lesions, pulmonary hypertension), hypergammaglobulinemia. Antibacterial, mucolytic, hypotensive, gastroprotective therapy was carried out, parenteral administration of systemic glucocorticosteroid drugs was initiated (methylprednisolone sodium succinate solution 250 mg intravenously drip 2 times with a transition to dexamethasone solution at a dose of 4 mg intravenously drip 5 times) followed by the addition of a tablet form of methylprednisolone 40 mg/ days and further titration of the dose to 16 mg/day, against the background of which stabilization of the general condition was noted, as well as pronounced positive dynamics of the skin pathological process, and therefore further administration of methylprednisolone 16 mg/day on an outpatient basis with a gradual dose reduction under the supervision of a rheumatologist is recommended place of residence.

Diet

Hypoallergenic diet

- Efficacy: therapeutic effect after 21-40 days

- Timing: constantly

- Cost of products: 1300-1400 rubles. in Week

During illness, it is important to exclude from the diet all foods that can provoke allergic reactions. It is necessary to completely remove chocolate, cocoa, eggs, and citrus fruits from the diet. If you have kidney failure, you should not eat too salty foods or foods containing a lot of potassium. Alcohol should be completely avoided and food should not be too cold or too hot.

It is important to adhere to the following recommendations:

- Eat in small portions and at least 6 times a day.

- Introduce foods containing vitamins C, B, K and A into your diet.

- The amount of salt per day should not exceed 8 g.

- It is important to eat plenty of fermented milk products to restore calcium reserves in the body.

- The menu should include vegetable soups, boiled vegetables, cereals with milk and regular ones, vegetable oils, sweet fruits, boiled meat and fish, white bread crackers.

- You need to drink green tea, herbal infusions, jelly and compotes.

- As you recover, the diet is adjusted.

Consequences and complications

If the disease is not treated on time, the following complications may occur:

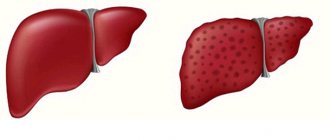

- liver and kidney failure;

- abdominal abscesses

- pulmonary hemorrhage;

- intussusception;

- polyneuropathy.

If, as the disease progresses, part of a blood vessel stretches and dilates, the risk of an aneurysm .

If during the inflammatory process the vessels narrow, the blood supply to individual organs and tissues may stop, which increases the likelihood of necrosis.

List of sources

- Dunaeva N.V., Nikitina O.E., Stukov B.V., Karev V.E., Mazing A.V., Lerner M.Yu., Lapin S.V., Totolyan A. Cryoglobulinemic vasculitis associated with chronic hepatitis B: clinical observations and literature review.

- Nasonov E.L., Baranov A.A., Shilkina N.P. Hemorrhagic vasculitis (Henoch-Schönlein disease) // Vasculitis and vasculopathies. - Yaroslavl: Upper Volga, 1999. - 616 p.

- Handbook of a practicing physician. Under. ed. Vorobyova A.I. “Medicine”, 1981.

- Shostak N.A., Klimenko A.A. Systemic vasculitis: new in classification, diagnosis and treatment. Clinician. 2015;9(2):8-12

- Shilkina N.P., Dryazhenkova I.V. Systemic vasculitis and atherosclerosis. Ter. Arch. 2007; 3: 84-92.