Antihypertensives (from other gr. hypo decrease and lat. tensio tension, pressure) are medications that lower blood pressure and are used primarily for the treatment of hypertension. Therefore, they are also called antihypertensive drugs.

Arterial hypertension is distinguished as primary (hypertension or essential hypertension) and secondary (symptomatic).

The causes of hypertension are not completely known. An important role in the development of the disease is played by prolonged psycho-emotional stress, chronic stress, age-related decrease in vascular elasticity, excessive consumption of table salt and a sedentary lifestyle.

Secondary (symptomatic) arterial hypertension occurs due to an adrenal tumor. The tumor secretes large amounts of adrenaline, which is released into the blood, causing an increase in blood pressure. Also, symptomatic arterial hypertension can occur with kidney disease. In such cases we talk about renoprival hypertension. Secondary hypertension can be a symptom of other diseases.

Classification of antihypertensive drugs

Blood pressure is maintained by several physiological mechanisms: peripheral vascular resistance, heart rate and circulating blood volume. Antihypertensives usually affect one or more mechanisms of blood pressure maintenance.

Drugs that reduce the activity of the sympathetic nervous system

- Central type of action (clonidine, methyldopa, guanfacine, moxonidine)

- Beta-blockers (metoprolol, nebivolol, bisoprolol, atenolol, betaxolol, talinolol, carvedilol)

- Alpha blockers (prazosin, doxazazin, terazosin)

- Gagnlioblockers (hexamethonium benzosulfonate, azamethonium bromide, etc.)

Peripheral vasodilators (peripheral vasodilators)

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (enalapril, lisinopril, ramipril, captopril, perindopril, moexipril, spirapril)

- Angiotensin II receptor antagonists (valsartan, irbesartan, losartan, telmisartan, eprosartan)

- Calcium ion antagonists (nifedipine, amlodipine, lacidipine, isradipine, verapamil, diltiazem)

- Antispasmodics of myotropic type of action (papverine, bendazole)

Agents affecting water and electrolyte balance

- Diuretics (hydrochlorothiazide, indapamide, torsemide, chlorthalidone, spironolactone)

In addition to the drugs listed in the classification, blood pressure can be lowered by drugs that reduce psycho-emotional stress. For example, sedatives or tranquilizers.

Antihypertensive therapy as the basis of neuroprotection in modern clinical practice

Arterial hypertension (AH) is one of the most pressing problems of modern therapy, cardiology and neurology. The prevalence of hypertension in European countries, including the Russian Federation, is in the range of 30–45% of the general population, with a sharp increase as the population ages. Hypertension is a leading risk factor for the development of cardiovascular diseases (CVD), such as myocardial infarction (MI), cerebral stroke, coronary heart disease (CHD), chronic heart failure (CHF), as well as cerebrovascular diseases (CVD): chronic cerebral ischemia brain (CHI), hypertensive encephalopathy, ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, transient ischemic attack. Hypertension is the most common component of comorbidity in the practice of any doctor, present in 90% of cases of all possible combinations of diseases [1, 2]. The most common comorbidity is hypertension with atherosclerosis or dyslipidemia. The main complication of atherosclerosis of the coronary arteries is coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction and cardiosclerosis, leading to progressive CHF, and damage to the main arteries of the brain is manifested by symptoms of CCI with the subsequent development of vascular dementia or cerebral stroke [3, 4]. Today, about 9 million people in the world suffer from CVD. All this makes it relevant to constantly study the problem of early diagnosis and correction of hypertension in order to prevent the most common CVDs and CVDs [5].

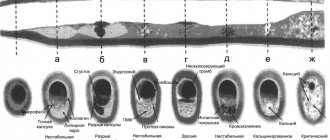

Quadruple antihypertensive combination - capabilities and advantages

The key point in the use of antihypertensive therapy remains effective control of blood pressure (BP) and achieving optimal values, determined individually for each patient, taking into account all existing risk factors for CVD and concomitant conditions. Today, five main classes of antihypertensive drugs are recommended for the treatment of hypertension: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), calcium antagonists (CAs), beta-blockers (BBs) and diuretics, for which the ability to prevent the development of cardiovascular complications proven in numerous randomized clinical studies. All of these classes of drugs are suitable for initial and maintenance therapy, both as monotherapy and as part of combinations. Early start with rational combination therapy is a new approach recommended by modern guidelines for the treatment of hypertension [6, 7]. Let's consider which combinations of antihypertensive drugs are rational, well studied and most often prescribed in modern therapy. ACE inhibitors block the formation of angiotensin II from angiotensin I, preventing vasospasm and ensuring the maintenance of target blood pressure values. In clinical practice, the most commonly used drugs are enalapril, lisinopril, and captopril [7]. Enalapril has the most extensive evidence base for reducing overall mortality - 7 studies (n = 12,791 patients) [8]. Separately, it should be emphasized that in modern therapy it is enalapril that takes the lead in the treatment and prevention of CHF. Antihypertensive drugs from the diuretic group reduce the load on the myocardium, reducing circulating blood volume (CBV). A decrease in blood volume under the influence of diuretics is achieved due to the accelerated removal of fluid from the body. Loop diuretics reduce the reabsorption of Na+, K+, Cl– in the thick ascending part of the loop of Henle, reducing fluid reabsorption, have a fairly pronounced and rapid effect and, as a rule, are used only for emergency care (for forced diuresis in pulmonary edema, overhydration, etc. .). The most well-known drug in this group is furosemide. Thiazide-like diuretics (hypothiazide, indapamide, chlorthalidone), reducing the reabsorption of Na+ and Cl– in the thick segment of the ascending loop of Henle and in the initial part of the distal tubule of the nephron, reduce urine reabsorption. When taken systematically in patients with hypertension, the risk of cardiovascular complications is reduced. A representative of thiazide-like diuretics, indapamide does not cause disturbances in lipid and carbohydrate metabolism, and therefore is widely used in patients with various types of metabolic disorders, unlike other representatives of this class. A combination with BBs is also possible, which act on the vascular system by stimulating b-adrenergic receptors and are widely used in clinical practice in patients with hypertension and vascular comorbidity. BBs reduce the heart rate, lengthening diastole and improving blood supply to the myocardium, since the heart receives substances necessary for functioning from the blood only during diastole. Independent randomized studies confirm a decrease in heart rate and an increase in life expectancy in patients with long-term use of BB [5]. The most popular beta-blockers with a proven improvement in prognosis, including in patients with coronary artery disease, are metoprolol, bisoprolol, and carvediol. ACs are used no less widely than BBs in the clinical practice of treating hypertension. These drugs block the entry of calcium into vascular smooth muscle cells and cardiomyocytes. This blockade is accompanied by vasodilation, but at the same time, a weakening of myocardial contractility. In addition, AKs reduce the activity of the sinus node, and when blood pressure drops, they can cause tachycardia. Thus, with a brief discussion of the most frequently prescribed classes of drugs in the form of mono- or combination therapy, taking into account evidence-based medicine, additional properties and, of course, the economic component of treatment, it was possible to identify the leaders. This is how the modern low-dose neuroprotective combination drug Hypotef was created. Hypotef contains enalapril, indapamide, metoprolol tartrate and vinpocetine; it has a complex effect, influencing all stages of the development of target organ damage in hypertension, which is especially important in patients with CVD. A special feature of Hypotef is not only the unique combination of the three most popular antihypertensive classes, which provide multifaceted organoprotective support and improve the prognosis, but also the nootropic vinpocetine included in the drug, which potentiates the antihypertensive effect and has a powerful evidence base for improving the state of cerebral circulation [9]. The effectiveness of vinpocetine has been repeatedly confirmed in large-scale studies, so it has been shown that vinpocetine therapy helps reduce the severity of neurological symptoms such as headache, dizziness, tinnitus in patients with hypertension, as well as a significant improvement in mood and memory. In patients after an ischemic stroke, the use of vinpocetine, compared with the control group, contributed to a greater extent to the regression of speech, motor and memory disorders [9]. Hypotef has a uniform, long-term antihypertensive effect with the achievement of target blood pressure values comparable to the effect of 20 mg of enalapril or 50 mg of metoprolol [10]. The gradual decrease in blood pressure was well tolerated by patients, without symptoms of hypotension, even with a significant decrease in blood pressure (maximum to –31.3/16 mmHg over 12 weeks of treatment) [11]. A comparative study of FORCAGE with modern antihypertensive combinations showed the same organ-protective effectiveness of Hypotef in relation to the kidneys and heart and higher efficiency in reducing vascular age (1.5 times), arterial stiffness (1.5 times) and intima-media thickness (1.7 times) [12, 13]. Hypotef normalizes diurnal variability: in the Hypotef group, the number of “dippers” increased by 32%, and in the group taking other modern combinations, only by 25%, while in this group the number of patients with an excessive nocturnal decrease in blood pressure increased. With a comparable hypotensive effect, Hypotef was well tolerated by patients, there were no cases of hypotension, and patient compliance was higher than in the comparison groups [11–13]. The possibility of effective use of the drug Hypotef in a patient with hypertension and a high additional risk can be considered in the following clinical example.

Patient A., born in 1965, came to see a general practitioner at the district clinic with complaints of rapid heartbeat, headache, frequent dizziness, “noise and ringing” in the ears, severe fatigue during exercise, and memory impairment.

Heredity: father - stroke, acute coronary syndrome at the age of 50 years; mother - hypertension, coronary artery disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, sister - hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Anamnesis. Over the course of several years, blood pressure increased to max 200/110 mm Hg. Art., currently receives enalapril 5 mg 2 times a day as antihypertensive therapy, adapted to 150/90 mmHg. Art. Several years ago, fasting hyperglycemia was first identified; a test with 75 g of glucose revealed impaired glucose tolerance. Since then, the patient has been following a diet, monitoring her weight, and her weight is stable.

Past illnesses: frequent colds, duodenal ulcer.

Epidemiological history: tuberculosis, viral hepatitis, diabetes mellitus.

Bad habits: smokes, does not abuse alcohol.

Allergy history: Pinosol nasal drops - Quincke's edema.

Current condition: general condition is satisfactory.

On physical examination: the patient's height is 175 cm, weight 95 kg, body mass index - 31 kg/m2, waist circumference - 112 cm, hip circumference - 100 cm, and the waist-to-hip ratio is > 0.95, indicating abdominal type of obesity, which is usually combined with metabolic disorders. Hypersthenic physique. The skin is of normal color. Subcutaneous fat tissue is moderately developed. There is no swelling. In the lungs there is vesicular breathing, no wheezing. NPV = 16 per minute. Heart sounds are clear, rhythmic, heart rate = 88 per minute. Blood pressure = 152/90 mm Hg. Art. The abdomen is soft, painless on palpation. The liver is not enlarged. The effleurage symptom is negative on both sides.

Based on the results of laboratory and instrumental examination, no changes in the results of clinical blood and urine tests were detected. Biochemical analysis is presented in table. 1.

According to echocardiography: signs of left ventricular hypertrophy. Left ventricular ejection fraction - 61%.

The results of 24-hour blood pressure monitoring (Table 2) confirmed the presence of hypertension, despite the therapy being taken. The average systolic blood pressure (SBP) per day was 154 mm Hg. Art. (daytime SBP - 157 mm Hg), diastolic blood pressure (DBP) - 95 mm Hg. Art., which exceeded normal values. A disturbance in the circadian rhythm of SBP of the non-dipper type was noted, i.e., lack of a sufficient reduction in blood pressure at night, which is especially unfavorable with regard to the development of complications such as stroke, heart attack, chronic cerebral ischemia and cognitive impairment.

Diagnosis: “Arterial hypertension, 1st degree, risk IV. NK - 0. Hyperlipidemia IIb. Obesity 1st degree. Visceral type of obesity. Prediabetes: impaired glucose tolerance. Impaired fasting glucose. Duodenal ulcer without exacerbation.”

Received therapy at the time of treatment: Enap 5 mg 2 times a day (morning, evening); Omez 20 mg 1 time/day (at night).

The therapy received was adjusted:

1) Enap was replaced with the drug Hypotef - 1 tablet in the morning and 1 tablet in the evening; 2) the drug pitavastatin 4 mg, 1 tablet in the evening after dinner was added to the therapy.

When the patient was re-examined after 3 months, it was revealed that during the therapy, the patient’s condition improved significantly: headaches regressed, general well-being improved, performance increased, the sensation of “noise and ringing” in the ears, as well as “lapses” in memory, disappeared. To assess the effectiveness of therapy, repeated 24-hour blood pressure monitoring was carried out; the results confirmed the achievement of target values - up to 125/80 mm Hg. Art. and normalization of the daily blood pressure profile (Table 3). Biochemical analysis showed achievement of target values for LDL and total cholesterol levels (Table 4). It was also noted that there was no worsening of carbohydrate disorders during the therapy.

Thus, rational antihypertensive therapy prescribed to the patient in the form of a low-dose combined neuroprotective drug Hypotef and statin therapy showed high effectiveness in a short time. The disappearance of symptoms such as headache, dizziness, tinnitus, as well as a subjective feeling of improved memory makes the patient committed to this therapy and makes it possible to carry out long-term treatment. The patient tolerates the prescribed therapy well; she is recommended to continue taking all previously prescribed medications under monitoring lipid levels and blood pressure.

Taking into account modern recommendations for the treatment of hypertension and data on the study of the clinical effectiveness of the drug Hypotef, it seems possible to talk about a truly rational solution to many problems in a patient with hypertension using one unique four-component neuroprotective drug - Hypotef, which can significantly improve the patient’s quality of life and avoid unsafe polypharmacy.

Literature

- Redon J., Olsen MH, Cooper RS, Zurriaga O., Martinez-Beneito MA, Laurent S. et al. Stroke mortality trends from 1990 to 2006 in 39 countries from Europe and Central Asia: implications for control of high blood pressure // Eur Heart J. 2011; 32: 1424–1431.

- Shishkova V.N. Neuroprotection in patients with arterial hypertension: minimizing an unfavorable prognosis // Therapeutic archive. 2014; 8: 113–118.

- Shishkova V.N. Cognitive impairment as a universal clinical syndrome in the practice of a therapist // Therapeutic archive. 2014; 11: 128–134.

- Stroke. Guide for doctors / Ed. Kotova S.V., Stakhovskoy L.V. M: MIA Publishing House, 2013.

- Shishkova. V. N., Adasheva T. V., Kapustina L. A. Fundamentals of stroke prevention in modern clinical practice // Doctor. 2018; 29 (7): 3–12.

- Chazova I.E., Zhernakova Yu.V. on behalf of the experts. Clinical recommendations. Diagnosis and treatment of arterial hypertension // Systemic hypertension. 2019; 16 (1): 6–31.

- 2018 EOK/EOAG Recommendations for the treatment of patients with arterial hypertension // Russian Journal of Cardiology. 2018; 23 (12): 143–228.

- Korzun A. I., Kirillova M. V. Comparative characteristics of ACE inhibitors. St. Petersburg: VMedA, 2003. 24 p.

- Chukanova E. I. Modern aspects of the epidemiology and treatment of chronic cerebral ischemia against the background of arterial hypertension (results of the CALIPSO program) // Neurology, neuropsychiatry, psychosomatics. 2011; 3 (1): 38–42.

- Evdokimova A. G. et al. Clinical effectiveness of combination antihypertensive therapy in fixed doses: focus on Hypoteff // Therapy. 2016; 6 (10): 68–78.

- Skotnikov A. S., Khamurzova M. A. Organoprotective properties of antihypertensive therapy as prevention of the development of “vascular” comorbidity // Treating Physician. 2017; 7: 16–24.

- Skotnikov A.S., Yudina D.Yu., Stakhnev E.Yu. Antihypertensive therapy of a comorbid patient: what to focus on when choosing a drug // Attending Physician. 2018; 2:24–30.

- Skotnikov A. S., Khamurzova M. A. New combinations for the complex treatment of arterial hypertension to help the general practitioner // Polyclinic. Cardiologist today. Special issue. 2017/2018; 1:47–55.

V. N. Shishkova, Candidate of Medical Sciences

FSBEI HE MGMSU named after. A. I. Evdokimova Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, Moscow

Contact Information

DOI: 10.26295/OS.2019.68.63.015

Antihypertensive therapy as the basis of neuroprotection in modern clinical practice / V. N. Shishkova For citation: Attending physician No. 6/2019; Page numbers in the issue: 68-73 Tags: antihypertensive therapy, organ-protective support, comorbidity, cerebral circulation

Basics of treatment of hypertension

Arterial hypertension is a dangerous disease that requires treatment. High blood pressure damages the vessels of the brain, heart and kidneys, overloads the heart, and leads to the progression of atherosclerotic changes in blood vessels. These disorders lead to heart failure and so-called cardiovascular disasters - stroke and heart attack.

When treating arterial hypertension, one always strives to act primarily on the cause that causes it. If the cause is unknown or cannot be eliminated, symptomatic treatment is performed.

The main goal of treating hypertension is to reduce blood pressure to the so-called target (safe) numbers. Most experts in the field of cardiology consider systolic (upper) pressure above 140 mm dangerous. rt. Art.

The selection of an antihypertensive drug by a doctor is usually carried out empirically (experimentally). One of the so-called drugs of choice is prescribed in a minimum dose with constant monitoring of blood pressure. If the selected dose is ineffective, it is increased to the next dose of this drug. If the target blood pressure figures cannot be achieved, a second antihypertensive drug with a different mechanism of action and a different point of application of physiological blood pressure maintenance is prescribed in parallel. This type of therapy for hypertension is called combination therapy.

Principles for choosing antihypertensive drugs

A.A.

UPNITSKY ,

Russian National Research Medical University named after. N.I. Pirogova, Moscow Arterial hypertension (AH) and its complications are widespread in the population today and carry a high risk of disability and death among the population, mainly of working age (cerebral stroke, myocardial infarction, chronic heart failure, end-stage renal failure, cardiac arrhythmias, etc.) .

At the same time, the effectiveness of blood pressure control in patients with hypertension remains unacceptably low for various reasons. This article presents an attempt to streamline the prescription of antihypertensive drugs by applying a specific algorithm for their prescription, including adequate monitoring of the ongoing antihypertensive therapy. The article uses the latest ESC/ESH-2013 recommendations, as well as the American JNC-8 of December 2013 for the treatment of hypertension (JAMA-2014, December, online). The work provides an original algorithm for choosing antihypertensive therapy, including methods and timing for assessing both the effectiveness and safety of antihypertensive therapy. At the beginning of the article, it is appropriate to provide a classification of arterial hypertension according to blood pressure level ( Table 1

).

Table 1. Classification of arterial hypertension by blood pressure level

| Category | Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg. Art. | Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg. Art. |

| Optimal | <120 | <80 |

| Normal | <130 | <85 |

| High normal | 130-139 | 85-89 |

| Hypertension 1st degree | 140-159 | 90-99 |

| Hypertension 2nd degree | 160-179 | 100 -109 |

| Hypertension 3rd degree | ≥180 | ≥110 |

Relationship between blood pressure and damage to the cardiovascular system and kidneys

The relationship between blood pressure and cardiovascular and renal complications and mortality has been studied in a large number of observational studies. Their main results are as follows:

1. Office BP is directly associated with the incidence of stroke, myocardial infarction, sudden death, heart failure and peripheral arterial disease (PAD), as well as end-stage renal disease (ESRD). 2. In individuals over 50 years of age, SBP appears to be a better predictor of clinical events than DBP. In elderly and senile people, pulse pressure (the difference between SBP and DBP) plays a possible additional prognostic role. This is also evidenced by a particularly high cardiovascular risk in patients with elevated SBP and normal or low DBP - isolated systolic hypertension (ISAH). 3. Blood pressure values measured outside the office, such as those obtained during ABPM and home blood pressure monitoring (HBP) are also related to clinical events. 4. The relationship between cardiovascular morbidity and mortality varies depending on the presence of other concomitant cardiovascular risk factors listed below.

Risk stratification criteria for arterial hypertension (recommendations of VNOK-2004)

Risk factors

Basic

- Men > 55 years old.

- Women > 65 years old.

- Smoking.

- Cholesterol > 6.5 mmol/L, or low-density lipoprotein cholesterol >.4.0 mmol/L, or high-density lipoprotein cholesterol < 1.0 mmol/L.

- Family history of early CCP (women <65 years, men <55 years).

- AO (OT ≥ 102 cm for men or ≥ 88 cm for women).

- CRP ≥ 1 mg/dl.

Additional

- NTG.

- Low physical activity.

- Increased fibrinogen.

Target organ damage (stage II hypertension) Left ventricular hypertrophy (ECG, echocardiography, radiography).

Microalbuminuria (30-300 mg/day). Ultrasound signs of thickening of the arterial wall (thickness of the intima-media layer of the carotid artery ≥ 0.9 mm) or atherosclerotic plaques of the great vessels. A slight increase in serum creatinine 115-133 µmol/l for men or 107-124 µmol/l for women. Associated clinical conditions (stage III hypertension)

Cerebrovascular diseases

- Ischemic stroke.

- Hemorrhagic stroke.

- Transient ischemic attack

Heart diseases

- Myocardial infarction.

- Angina pectoris.

- Coronary revascularization.

- Congestive heart failure

Kidney diseases

- Diabetic nephropathy.

- Renal failure (creatininemia > 2.0 mg/dL).

- Proteinuria (>300 mg/day).

Peripheral artery diseases

- Dissecting aortic aneurysm.

- Symptomatic peripheral artery disease

Hypertensive retinopathy

- Hemorrhages or exudates.

- Swelling of the optic nerve nipple.

Thus, to reduce cardiovascular risk and prevent the above-mentioned consequences of hypertension, along with a number of non-drug measures (control of body weight, metabolic profile, smoking control, limiting salt intake, cyclic aerobic exercise of sufficient intensity and duration, a full night’s sleep), it is necessary to achieve target blood pressure levels using primarily antihypertensive drugs.

So, how to choose them correctly? Requirements for the treatment of hypertension [1]:

- Smooth decrease in blood pressure.

- Patient compliance.

- Regression of target organ damage.

- Increasing life expectancy and improving its quality.

- Stable maintenance of blood pressure at the target level.

Target blood pressure is the blood pressure level at which the minimum risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality is recorded ( Table 2

).

Table 2. Target blood pressure levels

| Patient group | Target BP |

| General population of patients with hypertension | <140/90 mmHg Art. |

| Hypertension + diabetes, proteinuria <1 g/day | <130/85 mmHg Art. |

| AH + DM, proteinuria > 1 g/day | <125/75 mmHg Art. |

| AH + chronic renal failure | <125/75 mmHg Art. |

| Patients over 60 years of age | <150/90 mmHg Art. * |

| * JNC-8, JAMA, December 2014, online. | |

We propose to select antihypertensive drugs according to a certain scheme - an algorithm consisting of three main fundamental stages. The use of such an algorithm should help the doctor treating such patients to achieve maximum effectiveness and at the same time minimize the risk of side effects of the pharmacotherapy.

The first stage of choosing an antihypertensive drug is pathogenetic ( Fig. 1

). In a patient with hypertension, we suggest two steps at this stage. The first is compiling a list of drugs that effectively affect the pathogenesis of the symptom - high blood pressure. In other words, the doctor should try in each specific case to determine which hemodynamic factor “warms up”, so to speak, increased blood pressure [1-3].

Figure 1. Pathogenetic stage of selection of antihypertensive drugs

Selection of drugs depending on the cause of increased pressure

| Increased cardiac output | Increased peripheral resistance | Increased circulating blood volume |

|

|

|

Selection of drugs in accordance with their organoprotective properties

| Cardioprotective drugs | Cerebroprotective drugs | Nephroprotective drugs |

|

|

|

This factor may be, for example, increased cardiac output (in the “hyperkinetic” version of hypertension, as in hyperthyroidism, or in the early stages of hypertension in young and sometimes middle-aged people).

In patients with “experienced” hypertension, cardiac output is extremely rarely increased, and increased peripheral resistance comes to the fore in maintaining elevated blood pressure. First, it is caused by transient increases in peripheral arterial vascular resistance in response to increases in blood pressure (the meaning of this phenomenon is the protection of peripheral organs and tissues from hyperperfusion). Over time, hypertrophy of the middle muscular layer of arterioles—resistance vessels—develops, and increased peripheral resistance is fixed at the organic level. Another component of this “equation” may be an increased circulating blood volume (CBV), the so-called. volume-dependent hypertension. As a rule, these are patients with obesity (there are many small vessels in the adipose tissue with additional blood volume), with swelling or pastiness of the legs, if they are not caused by chronic venous insufficiency.

According to the assessment of the hemodynamic variant of hypertension by the attending physician, in the first case, the list of effective drugs will include those that reduce cardiac output (beta-blockers, centrally acting drugs, “rhythm-slowing” calcium antagonists) [1, 4]

In the second, this will be a list of drugs that reduce total peripheral vascular resistance (TPVR): ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor antagonists of the 1st subtype (sartans), calcium antagonists (all), centrally acting drugs (I1 receptor agonists - rilmenidine, moxonidine etc.), sympatholytics (dopegit), beta-blockers with a vasodilating effect (carvedilol, nebivolol, etc.), long-acting alpha-blockers (doxazosin, terazosin, etc.), diuretics (with regular use for at least 2-3 weeks .). The latter reduce OPSS due to the removal of sodium from the vascular wall, which leads to a decrease in OPSS both by reducing its edema and by reducing its response to vasoconstrictor stimuli.

In the third case, preference will be given to diuretics. It should be remembered that mixed hemodynamic options are possible, and in such cases, drugs are combined [5].

But, given the importance of target organ damage in hypertension and organ protection, the doctor must identify in each patient with hypertension his version of target organ damage: this could be the brain and its vessels (“cerebral” version according to the old classification), the heart - in the form changes in the left sections (hypertrophy or dilatation of the left atrium and ventricle), as well as damage to the coronary arteries with an obvious or latent form of myocardial ischemia (cardiac form of hypertension); kidneys (microalbuminuria); hyperazotemia indicates advanced stages of kidney damage in hypertension. It is also possible to detect changes in the vessels of the retina or arteries of the lower extremities (also often asymptomatic, but detected during a targeted examination).

In accordance with the identified “target” organ (“targets”), the doctor compiles, still at the same first stage, a list of antihypertensive drugs that have appropriate organoprotective properties for hypertension (cardio-, cerebro- or nephroprotective).

ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor antagonists of the 1st subtype (sartans), beta-blockers, calcium antagonists (to varying degrees), indapamide have proven cardioprotective properties; centrally acting antihypertensive drugs have moderate effects [1, 6–8].

Calcium antagonists (nimodipine) have cerebroprotective properties in hypertension, although this issue is not yet completely clear.

Nephroprotective properties in hypertension have been proven for ACE inhibitors, especially with a combination of hypertension and diabetes mellitus, angiotensin II receptor antagonists of the 1st subtype (sartans), as well as calcium antagonists.

Having now compared both lists (“hemodynamic” and “organoprotective”), the doctor should leave in the final list of the 1st stage only those drugs that are present in both lists simultaneously. This will be the final list of the 1st stage - a list of drugs that are effective in this particular case, but not yet taking into account their safety for the patient.

This aspect of drug selection is the subject of the second stage, in which the list of antihypertensive drugs that are effective for a given patient in a given situation, compiled at the first stage, should be considered from a different angle, namely: whether all effective drugs from this list will be safe for this patient. To solve this problem, we must return to the anamnesis (indications in the anamnesis of intolerance or unsatisfactory tolerability of certain drugs, including those related to those prescribed). Next, you should review the list of concomitant diseases in this patient - contraindications to taking certain medications may also be identified here. For example, if you have a history of bronchial asthma, drugs from the group of beta-blockers are contraindicated. These same drugs, with the exception of beta-blockers, which have vasodilating properties, are contraindicated in patients with stenosing atherosclerosis of the arteries of the lower extremities, with intermittent claudication. Beta-blockers are also contraindicated in cases of atrioventricular block above degree I/bradycardia less than 50 per minute. Alpha-blockers are contraindicated in case of concomitant angina pectoris, as they can cause an increase in anginal attacks. Sympatholytics, which have recently been used extremely rarely, are contraindicated in persons with peptic ulcer disease. Calcium antagonists are contraindicated in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) because they cause relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter and thereby may worsen the symptoms of GERD. Calcium antagonists, primarily verapamil, can significantly aggravate constipation and are therefore contraindicated in this category of patients. Diuretics can increase the level of uric acid in the blood, and therefore hyperuricemia and gout are contraindications for them. For carbohydrate metabolism disorders, the only safe diuretic is indapamide. A number of antihypertensive drugs can have a negative effect on the course and outcome of pregnancy. Therefore, a limited range of antihypertensive drugs is prescribed for it [1, 6, 7]:

- Methyldopa.

- Labetolol.

- Pindolol.

- Oxprenolol.

- Nifedipine SR.

- Hydralazine.

- For kidney disease - diuretics.

Thus, after the 2nd stage of selection, only drugs that are effective and at the same time safe for a patient with hypertension will remain on the list.

The third and final stage of choosing an antihypertensive drug is the stage of individualization of pharmacotherapy.

The first step is to decide what pharmacotherapy is indicated for this patient (mono-or combined). When resolving this issue, one should proceed from the degree of increase in blood pressure and the duration of hypertension. With long-term hypertension, with high numbers, you should start with a combination of antihypertensive drugs from the very beginning. At the same time, rational and irrational combinations of antihypertensive drugs are distinguished ( Fig. 2

).

possible combinations (only dihydropyridine calcium antagonists can be normally combined with β-blockers) Red continuous line: not recommended combination |

In cases of mild hypertension, not corrected by non-drug treatment methods (see above), and moderate hypertension, monotherapy is possible in some cases.

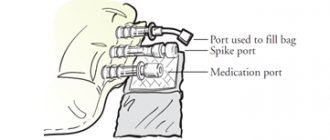

However, in the treatment of hypertension there is a rule: combinations of antihypertensive drugs with different mechanisms of action are preferable to high-dose monotherapy. Firstly, in combination, the effect is achieved by influencing different parts of the pathogenesis of hypertension, and secondly, with the right combination, the side effects of the drugs are mutually neutralized. For example, “escape” of the hypotensive effect due to the activation of counter-regulatory mechanisms manifests itself when taking arteriolar vasodilators by increasing cardiac output; when taking all antihypertensive drugs, except diuretics, due to sodium and water retention in the body; when taking diuretics – due to the activation of the body’s neurohormonal systems, in particular the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system [1, 5, 6]. The choice of method of administration of an antihypertensive drug is determined by the clinical situation: in case of an acute rise in blood pressure, drugs are administered parenterally (intravenously or intramuscularly), as well as sublingually (Capoten, Prazosin, Corinfar, etc.) ( Table 3

). It should be noted that these drugs have a short onset of effect and at the same time a short half-life. That is, they should be used specifically in acute situations, and are much less suitable for long-term use. The fact is that when taking short-acting drugs, there are constant fluctuations in their concentration in the blood, and after them, fluctuations in their hypotensive effect, which is accompanied by significant variability in blood pressure during the day. The latter is an unfavorable factor; in particular, the risk of hypertension complications increases. In addition, when taking the last dose of such a drug, even before bedtime, it still does not prevent the morning rise in blood pressure.

Table 3. Medicines for self-relief of blood pressure rise (according to M.V. Leonova, 2012, as amended)

| Drug (INN*) | Method of administration | Start of action | Maximum effect | Duration of action | Doses |

| Captopril | Inside, under the tongue | 15 minutes | 1-2 hours | 4-6 hours | 12.5-50 mg |

| Clonidine | Inside, under the tongue | 30 min | 1-2 hours | 8-12 h | 0.075-0.15 mg |

| Nifedipine | Orally or chew | 15 min 5 min | 30 min 15 min | 4-6 hours 4 hours | 10-20 mg |

| Prazosin | Inside, under the tongue | 15-30 min | 1-2 hours | 8 hours | 1-2 mg |

| Nitroglycerine | Under the tongue, lingual spray | 1 min | 15 minutes | 30 min - 1 hour | 0.3-0.5 mg |

| * International nonproprietary name. | |||||

Here it should be recalled that in case of exacerbation of hypertension, one should try to identify its cause.

In this case, we may encounter the patient’s abuse of table salt, alcohol, taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to relieve pain (arthrosis, arthritis, sciatica, headaches, etc.), constant lack of sleep for some reason, non-compliance with the recommended pharmacotherapy (skipping medications). Therefore, long-acting drugs with a long half-life are indicated for continuous maintenance antihypertensive therapy. Another important advantage of drugs with a long duration of action is the possibility of taking them once or twice a day, which helps to increase patient adherence to treatment (according to some data, in the treatment of hypertension during the year it is about 40%). Obviously, this does not mean adequate blood pressure control.

In this regard, the antagonist of angiotensin II receptor subtype 1, candesartan, is of interest; it has the longest half-life of all drugs in this group (more than 24 hours), which makes it possible to achieve blood pressure control also in the morning. In addition, candesartan has advantages over other drugs in cases of combination of hypertension with chronic heart failure, type 2 diabetes mellitus, diabetic nephropathy, proteinuria, and left ventricular myocardial hypertrophy.

To date, the results of 14 placebo-controlled studies with candesartan in 3,377 patients with hypertension are available. Daily doses of the drug ranged from 2 to 32 mg with a follow-up period of 4 to 12 weeks. Baseline blood pressure (diastolic) (DBP) ranged from 95 to 114 mmHg. Art. Within this dosage range, 2,350 patients received active candesartan therapy and 1,027 patients received placebo. In all studies, a significant hypotensive effect of candesartan was noted, which was dose-dependent, i.e., it was more pronounced the higher the dose of candesartan.

From a safety standpoint, the absence of a “first dose effect” was demonstrated, i.e., when taking the first dose of candesartan, there was no sharp decrease in blood pressure. As with other antihypertensive drugs, the hypotensive effect of candesartan increased during the first two weeks and by the end of this period was already clearly expressed. Similar to other antihypertensive drugs, the maximum effect was observed at the end of the 1st month of therapy. Moreover, the hypotensive effect of candesartan did not depend on the age or gender of patients, as well as on race and ethnicity. Of particular note is the good tolerability of candesartan even at a daily dose of 32 mg.

As for the stability of the hypotensive effect, in studies lasting up to one year there was no evidence of the hypotensive effect of candesartan.

Comparative studies of candesartan and losartan in hypertension were also conducted (CANDLE, CLAIM I and II studies, meta-analysis by Zhenfeng Zh, Huillan Shi, Junya Jia et al.), which demonstrated the advantage of candesartan in terms of the severity of blood pressure reduction and its tolerability by patients.

Thus, candesartan has a long-term pronounced hypotensive effect, which depends on the dose of the drug.

The intervals between doses of antihypertensive drugs, with the exception of diuretics, are 2-3 half-lives of the drug and are indicated in the instructions for it. At the same time, one should keep in mind the possibility of reducing the duration of action of antihypertensive drugs when they are accidentally simultaneously prescribed with drugs that are inducers of hepatic metabolism, accelerating the metabolism of antihypertensive drugs in the liver and their excretion from the body. Inducers of hepatic metabolism include, in particular, phenobarbital, other anticonvulsants, rifampicin, etc. In such cases, the intervals between doses of antihypertensive drugs should be reduced [1, 6].

Duration of treatment. With a certain “experience” of hypertension in the body, a “reconfiguration” (“resetting”) of blood vessels, kidneys, brain, and heart occurs to work at elevated blood pressure. In addition, the body retains mechanisms that support hypertension (except for rare cases of surgical treatment of arterial stenosis, removal of adrenal aldosteroma, pheochromocytoma, thyroidectomy and some others). That is why, after normalization and stabilization of blood pressure, antihypertensive therapy should not be stopped. Another thing is that over time, especially in the warm season, it is permissible to reduce the dose and amount of antihypertensive drugs under the control of blood pressure and well-being, provided that all non-drug methods of lowering blood pressure are followed. Criteria for assessing the effectiveness and safety of antihypertensive therapy

To assess the effectiveness, along with assessing the dynamics of the patient’s well-being, office BP measurements should be used, as well as additional methods: 24-hour BP monitoring - ABPM, home measurement (HBP) by the patient.

When measuring office blood pressure, this should be done repeatedly at intervals of 2 minutes, following certain rules. In addition, to assess the safety of antihypertensive therapy, especially alpha-blockers, diuretics, ACE inhibitors and their combinations, blood pressure should be measured in clinostasis (lying down, after 5 minutes) and in orthostasis (after 2 minutes in an upright position). A pronounced decrease in blood pressure in orthostasis (by 20 mm Hg or more) increases the risk of cardiovascular complications and may adversely affect the patient’s well-being.

Additional methods of blood pressure control (ABPM and DMBP) make it possible to avoid unnecessary and unsafe therapy for the patient in the case of “white coat hypertension”, to identify patients with a predominantly nocturnal rise in blood pressure or with an insufficient or excessive decrease in blood pressure at night. The information obtained is valuable for the correct selection and evaluation of antihypertensive therapy [1, 2, 6–8].

To help the practitioner, we provide a list of some fixed combinations of antihypertensive drugs ( Table 4

).

Table 4. Fixed combinations of antihypertensive drugs

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor + calcium antagonist |

| Enalapril 5 mg + felodipine 5 mg Benazepril 10/20 mg + amlodipine 2.5/5 mg Perindopril 5/10 mg + amlodipine 5/10 mg Trandolapril 1/2/4 mg + verapamil SR 180/240 mg Enalapril 10 mg + diltiazem 180 mg Lisinopril 10/20 mg + amlodipine 5/10 mg Ramipril 5 mg + felodipine retard 5 mg |

| Angiotensin II receptor antagonist + calcium antagonist |

| Valsartan 80 mg + amlodipine 5 mg |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor + diuretic |

| Lisinopril 10/20 + hydrochlorothiazide 12.5/25 mg Captopril 25/50 + hydrochlorothiazide 12.5/25 mg Enalapril 20 mg + hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg Enalapril 10 mg + hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg Enalapril 10 mg + hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg Quinapril + Hydrochlorotiazide 12.5/25 mg Lisinopril 10 mg + hydrochlorotiazide 12.5 mg ramipril 5 mg + hydrochlorotiazide 12.5 mg fosinopril 20 mg + hydrochlorotiazide 12.5 mg moexipril 15 mg + hydrochlorotiazide 25 mg cylized 5 mg + hydrochlorotiazide 12.5 mg Perindopril 2 mg + indapamide 0.625 mg Perindopril 4 mg + indapamide retard 0.5 mg |

| Angiotensin II receptor antagonist + diuretic |

| Losartan 50 mg + hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg Valsartan 80 mg + hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg Eprosartan 600 mg + hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg Irbesartan 150/300 mg + hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg Telmisartan 80 mg + hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg Telmisartan 40/8 0 mg + hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg Candesartan 8 mg + hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg |

| β-blocker + diuretic |

| Pindolol 10 mg + clopamide 5 mg Bisoprolol 2.5 mg + hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg Propanolol 40/80 mg + hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg Bisoprolol 2.5/5/10 mg + hydrochlorothiazide 6.25 mg Metoprolol 50/100 mg + hydrochlorothiazide 25/50 mg Atenolol 100 mg + chlorthalidone 25 mg Atenolol 50/100 mg + chlorthalidone 12.5/25 mg Calcium antagonist + |

| β-blocker |

| Felodipine retard 5 mg + metoprolol succinate 50 mg Amlodipine 5 mg + atenolol 50 mg |

In conclusion, we urge all doctors involved in the treatment of hypertension in outpatient and inpatient settings to approach the diagnosis and treatment of patients with hypertension thoughtfully, clearly understanding the sequence of actions for diagnosis and selection of antihypertensive therapy, and we wish them good luck on this thorny path.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Recommendations for the treatment of arterial hypertension. ESH/ESC 2013. Russian Journal of Cardiology, 2014, 1: 5-92. 2. VNOK. Prevention, diagnosis and treatment of arterial hypertension. Russian recommendations (fourth revision). M., 2010. 3. Recommendations of VNOK. Diagnosis and treatment of arterial hypertension. M., 2009: 5-34. 4. Bauchner H, Fontanarosa PB, Golub RM. Updated guidelines for management of high blood pressure: Recommendations, review, and responsibility. JAMA, 2013, December 18. 5. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL et al. 2014 Evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: Report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA, 2013, December 18. 6. Peterson ED, Gaziano JM, Greenland P. Recommendations for treating hypertension: What are the right goals and purposes? JAMA, 2013, December 18. 7. Sox HC. Assessing the trustworthiness of the guideline for management of high blood pressure in adults. JAMA, 2013, December 18. 8. Wood S. JNC 8 at Last! Guidelines Ease Up on BP Thresholds, Drug Choices. Medscape, December 18 (https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/817991).

Features of the treatment of hypertension

Therapy for hypertension is not carried out periodically, but with the constant use of an antihypertensive drug.

It is an extremely dangerous misconception to use the drug only “when there is pressure.” If hypertension is diagnosed, there is a tendency for a persistent increase in systolic pressure above 140 mm. rt. Art., an antihypertensive drug is taken daily, preferably at the same time, under constant monitoring of blood pressure, for life.